Israel’s occupation of the West Bank rests, in part, on a multiplicity of laws. Ra’anan Alexandrowicz examines them in his probing documentary, The Law In These Parts, which is currently being presented online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation.

The system, drawn up before Israel’s conquest of the West Bank in 1967, is based on The Hague Regulations and the Geneva Conventions. It was largely devised by Meir Shamgar, the military advocate general from 1963 to 1968 and the chief justice of the Supreme Court from 1983 to 1995.

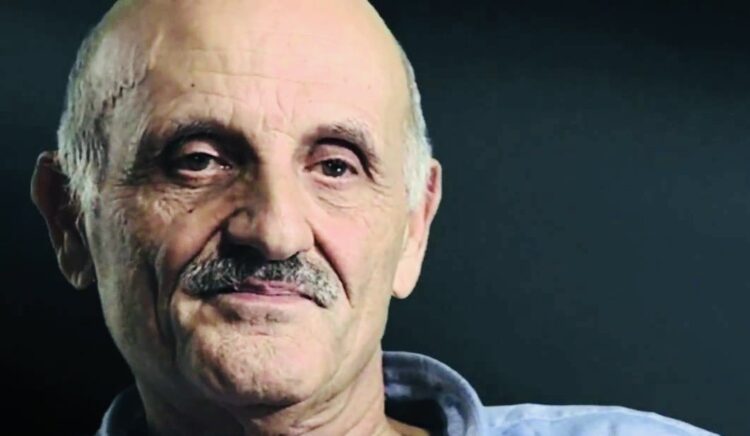

In his film, Alexandrowicz interviews Shamgar as well as his retired colleagues, who established the legal underpinnings of Israel’s occupation.

With Israel’s victory in the Six Day War, one million Palestinian Arabs who had lived under Jordanian rule suddenly found themselves under the thumb of a new occupying force. In the first year of the Israeli era, Israel enacted hundreds of edicts designed to “bring back life to normal,” says Dov Shefi, an advisor to the Israeli army from 1967 to 1968.

Israeli law was not imposed on Palestinians in the West Bank because Israel had no intention of annexing it or conferring citizenship on its Palestinian inhabitants, explains Shefi.

Military courts were set up in West Bank towns to deal with an upsurge of terrorism and Palestinian demonstrations protesting Israel’s presence, says Avraham Pachter, a military prosecutor from 1967 to 1970.

Convicted terrorists who had attacked civilians were not protected by the laws of warfare in the Geneva Conventions, Shefi points out. And Palestinians who helped terrorists, even unintentionally, could be arrested.

Alexander Ramati, a military judge from 1980 to 1981, rejected arguments from defendants’ lawyers that their clients were prisoners of war.

Shefi maintains that Israel was not in violation of the Geneva Conventions by allowing Israeli civilians to settle in the West Bank. They moved there voluntarily and were thus exempt from the provisions of the conventions, he claims.

Israel seized Palestinian lands by citing security imperatives, and the Israeli Supreme Court endorsed this rationale. When Ramati informed the then minister of agriculture, Ariel Sharon, that he could appropriate uncultivated Palestinian lands under Ottoman laws, he expanded Israel’s land holdings in the West Bank.

Shamgar helped Israel consolidate its grip on the West Bank by ruling that it could make “temporary” use of Palestinian lands. He claims the Supreme Court did not involve itself in political decisions with respect to the West Bank, but Alexandrowicz begs to differ.

He raises another contentious issue by saying that Israel governs the West Bank with two different sets of law — one for Palestinians and another for Israeli settlers.

During the first Palestinian uprising, from 1987 to 1993, Palestinians filed a plethora of petitions with the Supreme Court dealing with issues ranging from home demolitions and restrictions on movements to deportations and targeted killings of terrorists.

It would appear that the court has played an ambivalent role in such rulings. While it has urged the army to exercise restraint, the consensus is that it has legitimized the army’s operations and therefore justified the occupation. But absent the court’s intervention, Israel’s occupation would have been harsher.

In 1999, in a rare verdict, the court issued a ruling generally forbidding torture during interrogations of suspected terrorists. Jonathan Livny, who was an advocate general in the military, admits he was aware of such practices. But he reminds Alexandrowicz that Israelis think their personal security is directly linked with the success of security forces extracting vital and actionable information from terrorists.

It’s clear that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank has raised many thorny issues, some of which will remain unresolved.