I remember that day as clearly as yesterday.

Twenty years ago on November 4, on a typically cool autumn afternoon in Toronto, I greeted my Israeli friends, Arie and Ida, at my front door with terrible news. They had been out shopping and hadn’t heard what had happened just hours earlier.

Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister of Israel, had been assassinated in Tel Aviv, their hometown, by Yigal Amir, a right-wing Jewish fanatic who fiercely opposed the Oslo accords, signed in 1993 and 1995 by Israel and the Palestinians.

Aryeh, a bank executive, and Ida, an English-as-a-second-language teacher, rushed to the television and raptly watched the newscasts. A few minutes later, Aryeh, downcast, went into the kitchen. As he sat on a chair in silent contemplation, his head slumped in anguish, tears rolled down his cheeks.

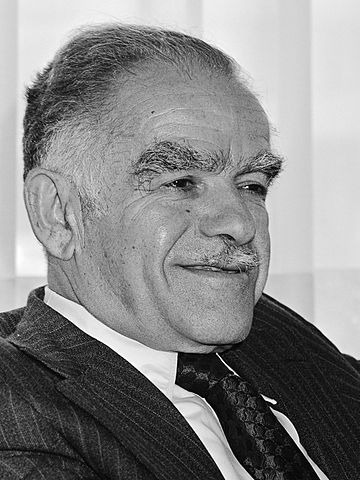

I was shocked, too. I had followed Rabin’s career since the 1967 Six Day War, when he was chief of staff of the Israeli armed forces. And I had interviewed him after he had stepped down as minister of defence in the national unity government. Less than two years later, Rabin, the leader of the Labor Party, was prime minister again, having defeated the Likud’s Yitzhak Shamir in the 1992 general election. Appointed prime minister in 1974 after the resignation of Golda Meir, Rabin resigned in 1977, following disclosures that his wife had opened an illegal bank account in the United States, where he had served as Israel’s ambassador from 1968 to 1973.

As the 20th anniversary of Rabin’s murder approaches, he probably would have been dejected to learn that the Oslo agreements are in tatters. The relationship between Israel and the Palestinian Authority — a body created by Oslo — is tense. And the Palestinians of the West Bank are in open revolt against Israel’s 48-year occupation. Since October 1, ten Israelis and 50 Palestinians have been killed in attacks and clashes.

Judging by events on the ground, it seems as if little or nothing has changed since the hopeful days of the Oslo agreements.

Oslo was the culmination of months of secret talks between Israeli and Palestinian representatives in Norway. Rabin placed Shimon Peres, the foreign minister, in charge of the file. He, in turn, delegated it to Yossi Beilin, the deputy foreign minister, who worked closely with two Israeli academics, Yair Hirschfeld and Ron Pundak.

Although Rabin approved of the talks, he could hardly be classified as a dove. As a young officer in the 1948 War of Independence, he oversaw the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs from Lydda and Ramla. At the height of the first Palestinian uprising in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, he ordered Israeli soldiers to break the bones of Arab rioters. He was tough as nails.

By any measure, Rabin was a security hawk, though he had once described Jewish settlements in the West Bank as a malignant “cancer” that would transform Israel into an “apartheid” state. Rabin was suspicious of Palestinian intentions and was opposed to full Palestinian statehood, but he believed Israel had a vested interest in settling the Arab-Israeli conflict so it could focus its attention on the looming threat posed by a resurgent and hostile Iran.

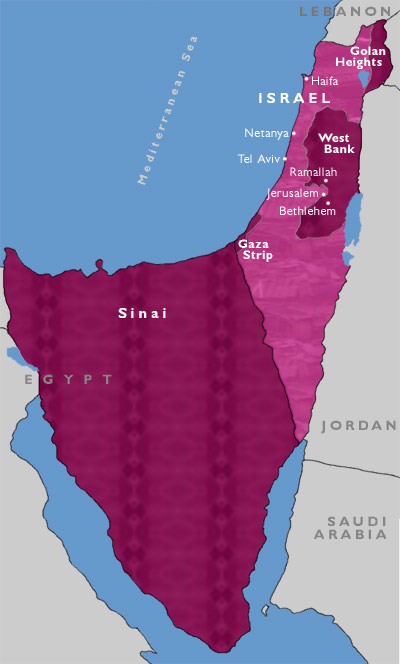

Proceeding from the assumption that Israel had nothing to lose by testing the Palestinians, Rabin allowed the negotiations with the Palestinians to continue. By August 1993, Israel and the PLO had reached an understanding. An interim agreement granting the Palestinians self-rule in parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was to followed in five years by a peace treaty based on United Nations Resolutions 242 and 338.

Oslo did not define the borders of the enclave the PLO would govern, nor did it stipulate a ban on the building of Jewish settlements in the occupied territories.

On September 13, the finished agreement, known as the Declaration of Principles, was signed by Rabin and the chairman of the PLO, Yasser Arafat, at a ceremony on the lawn of the White House in Washington, D.C.. The United States did not broker the accord, but U.S. President Bill Clinton was highly supportive of it.

By that juncture, the PLO had recognized Israel’s existence and Israel had recognized the PLO as the “representatives of the Palestinian people.”

Tellingly enough, Rabin appeared to be in physical pain as he tentatively shook hands with Arafat, his longtime nemesis. Peres was notably more relaxed.

The first step in implementing Olso was taken shortly afterward, when Israel withdrew from Jericho and segments of the Gaza Strip and Arafat set up the headquarters of the Palestinian Authority in Gaza City.

Right-wing Israeli nationalists, spearheaded by Benjamin Netanyahu, the leader of the Likud Party, denounced Oslo as a sellout and betrayal of Israel’s historic claims to the West Bank. Palestinian rejectionists issued denunciations as well, complaining that Oslo was fatally flawed. They charged that Oslo did not promise the Palestinians statehood, an end to the occupation or a moratorium on Jewish settlement construction.

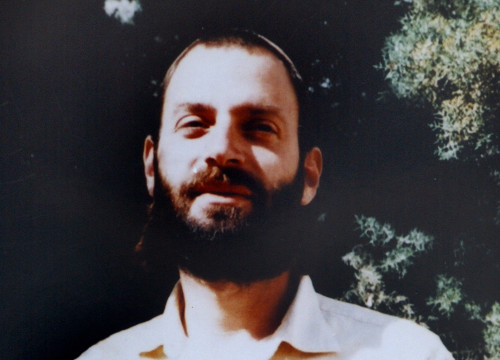

Baruch Goldstein, an America-born settler, fired the first shot at Oslo. In February 1994, he killed 29 Palestinian worshippers in Hebron’s Ibrahimi mosque, which Israeli Jews refer to as the Tomb of the Patriarchs. In response, Hamas — an Islamic movement opposed to Israel’s existence — launched a suicide bombing campaign which would claim the lives of hundreds of Israelis and leave increasing numbers of them disillusioned about the possibility of coexistence with the Palestinians.

Rabin, however, was not deterred by these setbacks. In 1995, Israel and the Palestinian Authority signed the second Oslo accord, for which Rabin needed the support of Arab parliamentarians to push through the Knesset.

Oslo II divided the West Bank into three distinct zones — Area A, which was to be fully under Palestinian control; Area B, which was to be jointly administered, and Area C, which was to be completely under Israel’s security and civil jurisdiction. Comprising 60 percent of the West Bank’s land mass, Area C — the site of Israel’s network of settlements — broke up its geographic contiguity.

Rabin, a cautious peacemaker, preferred this kind of an arrangement. In a speech on the eve of his assassination, he spoke frankly. “We would like this to be an entity which is less than a state and which will independently run the lives of the Palestinians under its authority,” he said. “The borders of the State of Israel, during the permanent solution, will be beyond the lines which existed before the Six Day War. We will not return to the June 4, 1967 lines.”

It’s clear that Rabin was prepared to give the Palestinians a measure of autonomy rather than full-fledged sovereignty after permanent status talks resolved such difficult issues as borders, settlements and Palestinian refugees.

Israeli hardliners like Yigal Amir, a religious nationalist studying at Bar-Ilan University, were deeply opposed to even minimal concessions to the Palestinians. And so he assassinated Rabin on November 4, 1995 at a peace rally in the heart of Tel Aviv.

Rabin’s successor, Shimon Peres, lasted less than a year, losing the 1996 election to Benjamin Netanyahu, a harsh critic of Oslo who had spoken at rallies where effigies of Rabin in a Nazi SS uniform had been displayed.

Netanyahu, in keeping with Likud ideology, was less than eager to fulfill Israel’s Oslo pledges. Nor, for a while, was he even willing to meet Arafat.

Palestinian mistrust grew exponentially as Israel expanded its settlements in the West Bank and announced plans to build thousands of apartment units in Har Homa, a neighborhood in East Jerusalem. Israel annexed eastern Jerusalem, which the Palestinians claim as their future capital, in 1967. Israeli suspicions and fears were fanned by continuing suicide attacks, Arafat’s tolerance of violence and the demonization of Israel and Jews in Palestinian media and schools.

The spirit of Oslo was further dampened by the failure of the U.S.-sponsored Camp David summit in July 2000 — which brought together Ehud Barak, the new Israeli prime minister, and Arafat for talks about final status issues — and by the eruption of the second Palestinian uprising in September 2000. This intifada was much more violent and costly than the first one in 1987, and it hardened Israeli public opinion on the Palestinians.

Both sides tried to save Oslo in a desperately-mounted summit in Taba in January 2001, but they fell short of the mark.

In the wake of a massive suicide bombing in Netanya in 2002, in which 30 Israelis were killed, the Israeli army reoccupied six major towns in the West Bank it had relinquished in 1995. Operation Defensive Shield, Israel’s biggest military offensive in the West Bank since the Six Day War, signified the demise of Oslo.

The United States attempted to revive Oslo in succeeding years, but to no avail. An Israeli prime minister, Ehud Olmert, came close to signing a breakthrough agreement with the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, in 2008. But the whiff of scandal, which would drive Olmert out of office, dissuaded Abbas from taking the final steps.

Since then, Oslo has been on life support, its foundations having been chipped away by Israel, the Palestinian Authority and Hamas.

No one will ever know how Oslo would have fared had Rabin lived. Would he have proceeded with the peace process in the face of terrorism? Would he have accepted a full-fledged Palestinian state, or something considerably less? Or, in the worst-case scenario, would he have abandoned Oslo in despair?

This much, however, seems certain. Rabin was a courageous politician who was prepared to take risks for the sake of achieving peace. Two decades on, though, Israel has shifted to the right, Israeli society has become more polarized, and Rabin’s pragmatic dream of resolving the Arab-Israeli dispute through diplomatic means has crumbled, leaving Israelis and Palestinians bitter and at loggerheads yet again.