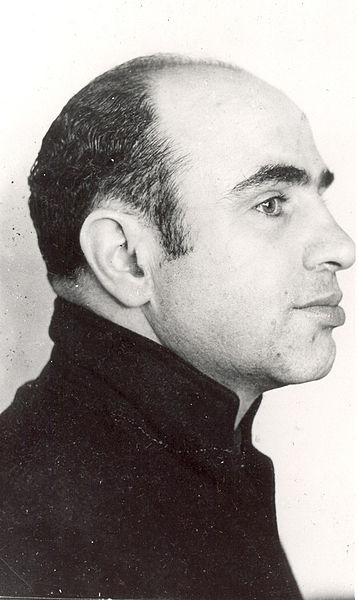

Probably the most infamous American gangster of all time, Alphonse (Al) Capone maintains an iron grip on the popular imagination. Seventy years after his death, Capone’s mystique seems undimmed and indestructible, even though his tempestuous reign lasted only six years. Celebrated and cursed in a cascade of books and movies and in a tsunami of newspaper articles, he was a legend writ large.

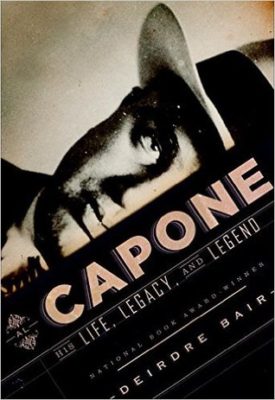

“His ascent in mobdom was phenomenal, his time at the top sensational, and his downfall meteoric,” writes his newest biographer, Deirdre Bair, in Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend (Penguin Random House).

In this thoroughly-researched and felicitously-written work, Bair delves into his Italian heritage, his chaotic childhood in Brooklyn, his spectacular rise in the Chicago underworld and his abrupt fall. It’s a journey marked by audacity, physical violence, bloodshed, celebrity and imprisonment.

Born on January 17, 1899, he was the son of Gabriele and Teresa Capone, immigrants from southern Italy. Capone’s father was by turns a baker, day labourer and barber. His mother was a stay-at-home garment worker who sired several children. Although Capone was a good student quick with numbers and figures, he was not academically-inclined. Quitting school at 14, he worked in a candy store, bowling ally, printing plant and shoe-shine stand before becoming a career criminal.

Capone caught the attention of crime boss Johnny Torrio after setting up his own protection racket. Torrio hired him as an enforcer and Capone carried out his orders with ruthless efficiency. By the age of 18, as far as Bair can ascertain, he had been responsible for at least six killings. Torrio farmed him out to Frankie Yale, who specialized in extortion and loan-sharking, among other pursuits. By then, Capone’s nickname was Scarface, a moniker he acquired after sustaining facial gashes in a barroom brawl over a woman.

A jack-of-all-trades for Yale, Capone was initially a bouncer and bartender, but subsequently, he kept Yale’s books, collected the earnings of his prostitutes and ensured that his bordellos ran smoothly. Oddly enough, as Bair points out, he despised prostitution, though he sampled the wares prodigiously.

Rising rapidly in the ranks, Capone was 26 when Torrio placed him in charge of the Outfit, which controlled hundreds of brothels, speakeasies and roadhouses. They, in turn, served as venues for gambling, prostitution and illegal alcohol sales during the era of Prohibition. Bair estimates its gross income was $105 million a year, or about $1.3 billion in 2015 U.S. dollar terms. Citing a Harvard Business School study, she says Capone managed the Outfit like a major corporation.

The Outfit was a going concern partly because so many corrupt local politicians and police were on its payroll. Another reason was that Capone was prepared to murder competitors in gang wars, which transformed him into a folk hero. There were roughly 700 gang-related deaths between 1920 and 1930, and Capone participated in more than 200 either directly or indirectly. Fearing possible repercussions, he purchased a small apartment building of which he was sole resident and whose front door was reinforced with steel plating.

A foppish dandy who favored luridly coloured but exquisitely tailored suits, with a handkerchief neatly folded in his breast pocket, Capone was driven around in a seven-ton, bullet-proof armoured Cadillac sedan that had been custom fitted at a cost of $20,0000 (over $250,000 in today’s currency).

In 1928, when Capone was at the height of his fame or infamy, the Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist Alva Johnston wrote a story about him in The New Yorker in which he described him as “the greatest gang leader in history.” Time magazine’s decision to put him on its March 24, 1930 cover added to his luster. “Al Capone had become a celebrity whose every doing was a feast for the newspaper paparazzi … Everything he said or did was fed into the endlessly grinding publicity mill, and within the small world of Chicago journalism he had camp followers and hangers-on who were always on the lookout for a scoop,” writes Bair. “He could not appear anywhere without a slew of reporters and photographers waiting to capture every word he said and every move he made …”

Damon Runyon, the famous newspaper columnist, regarded Capone as something of a role model. Like Capone, Runyon liked high living, flashy expensive clothes, gambling, playing the horses and womanizing. Capone, however, was not just a playboy. He had a genuine appreciation of culture, particularly Verdi’s Italian operas. And as Bair notes, he felt most secure and comfortable in the company of entertainers, many of whom got their start in his nightclubs and cabarets.

Although Capone was generally portrayed as a mobster, he preferred to call himself a businessman, a loyal husband (his wife, Mae, an Irish American, doted on him) and the loving patriarch of a large extended family. Bair points out he was always careful in his business dealings, never signing his name to any document, never establishing bank accounts and always working through intermediaries. “He was no dummy,” she quotes one of his associates as saying.

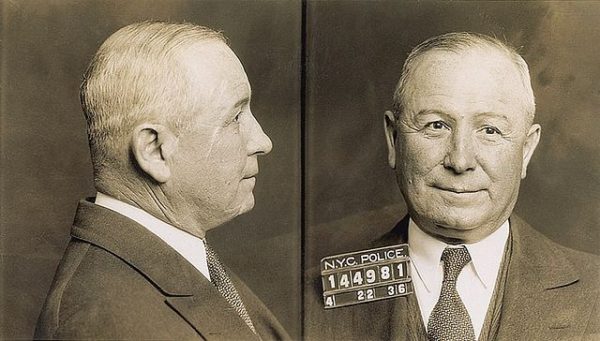

Despite the adulation and homage he received from the public, and despite the deference and respect that was paid to him by some elected officials, Capone was doomed by the strictures of class, being perceived as a “semi-literate outsider,” a “lower-class Italian,” a “dago” and a “wop.”

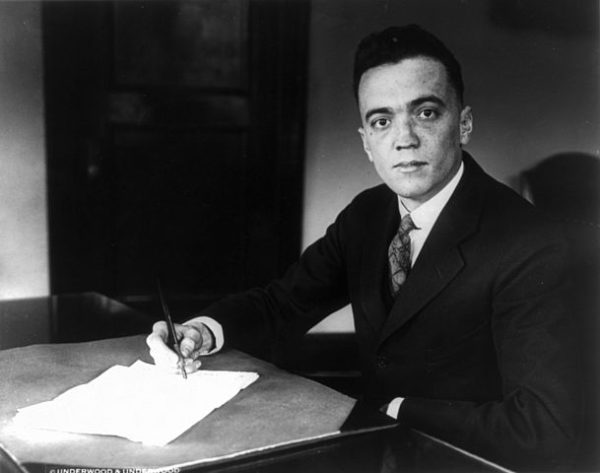

Capone’s fall was orchestrated by the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, who correctly deduced he could be convicted on charges of income tax evasion. On June 5, 1931, a federal grand jury indicted him on 24 counts of non-payment of income taxes. From that moment onward, the press pounced on him, with the Chicago Tribune taking the lead in vilifying Capone.

Having exhausted all his appeals, he was sent to prison to begin an 11-year sentence. It was there that he was diagnosed with neurosyphilis, a disease he presumably contracted from jousts with innumerable prostitutes. For the first few months at Alcatraz, he was mostly left alone, but eventually, he was taunted and accosted by fellow prisoners. Some even tried to extort money from him.

The rigors of prison affected his mind. After having been released to his family, physicians discovered his mental health had deteriorated so badly that he had the mentality of a seven-year-old and had to be supervised like a small child. He would never regain full mental cognition.

He died on January 21, 1947, a much-diminished figure. Bair believes he was penniless when he passed away. In his final years, he was totally dependent on the generosity of his brothers.

“Al Capone’s brief life was florid and dramatic, but his afterlife is even more colourful and outsized,” she says. “The frenzy of publicity he inspired during his lifetime has increased exponentially and shows no sign of slowing down.”

New books and films about Capone appear almost every year, and his face is on postage stamps in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Websites are devoted to him, and he’s featured in the Mob Museum in Las Vegas. In 2014, the Smithsonian magazine named him one of the hundred most influential Americans in the annals of the United States.

Although Bair has written a comprehensive and gripping account of a charismatic master criminal, she readily acknowledges that her biography is less than definitive and that Capone remains an elusive figure.

“All that we have are speculation and possibility, and they lead only to endless possibilities,” she observes. “For now, the only certainty is that as time passes and the man who was Al Capone recedes into history, the legend shows no sign of stopping.”