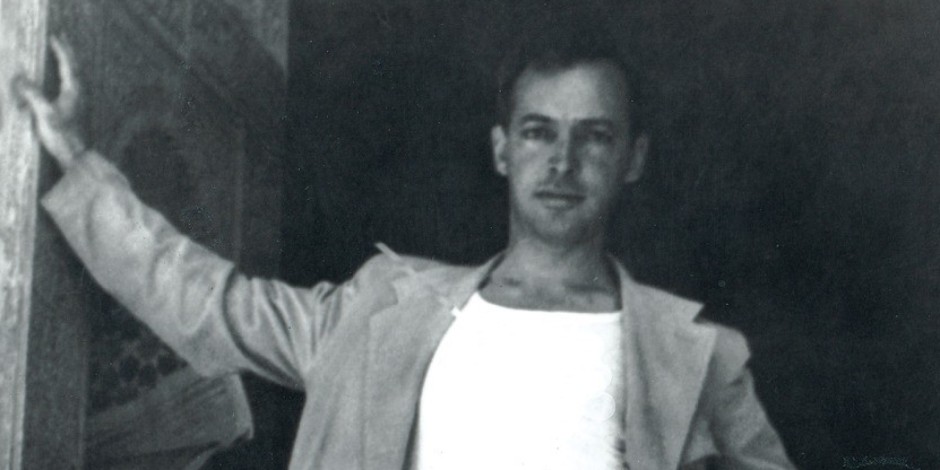

The late Saul Bellow was a colossus in American literature, the son of Yiddish-speaking Russian Jews who immigrated to the United States by way of Canada. In the estimation of his latest biographer, Zachary Leader, he was the most decorated writer in U.S. history, having won the Nobel Prize, the Pulitzer Prize and three National Book Awards.

Leader’s work, The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune 1915-1964 (Random House), takes a reader from his birth in Lachine, Quebec, a suburb of Montreal, to the publication of one of his finest novels, Herzog, for which he won his second National Book Award.

The first of two biographical volumes on Bellow, it examines his Russian Jewish roots, his formative years in Montreal and Chicago, his literary aspirations, his romantic attachments, his travels and his role in catapulting the Polish-born novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer to fame.

During this fecund period, Bellow wrote six novels apart from Herzog — Dangling Man (1944), The Victim (1947), The Adventures of Augie March (1953), Seize the Day (1956) and Henderson the Rain King (1959).

Leader, a professor of English literature at the University of Roehampton in London, delves deeply into his subject. Leader’s curiosity is boundless and his research is prodigious. He’s like a fly on the wall, buzzing around and apparently missing nothing. But there’s a flip side to his thoroughness. He inundates us with so much information that the book, running to more than 800 pages including notes and an index, occasionally reads like a bloated entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica. Nonetheless, The Life of Saul Bellow is a remarkable feat of scholarship.

As might have been expected, Leader allots considerable space to Bellow’s family, particularly his father, Abraham, who came from a shtetl on the border of Belarus and Latvia. By the time he had reached Canada, Abraham had failed as a farmer, baker, dry goods salesman, jobber, manufacturer, junk dealer and marriage and insurance broker.

In common with East European Jewish immigrants of the day, Abraham was an avid consumer of the Yiddish press, reading Der Kanader Adler as well as Der Forvertz. Bellow never forgot his father’s reading habits. In Herzog, when Aunt Zipporah pays a visit to friends, she brings a present of one fresh egg, “wrapped in a piece of Yiddish newspaper (Der Kanader Adler).”

According to family legend, Bellow — one of four children — was delivered by a drunken French Canadian doctor who had to be fetched from a bar. He was born in the year Sholem Aleichem visited Montreal and gave a reading at the Princess Theater, southwest of St. Lawrence Boulevard, which ran through the Jewish quarter.

By Leader’s estimation, Abraham was a difficult father. “Yes, I had a tyrannical father,” Bellow disclosed in a letter to a colleague. “Russian-Jewish fathers were naturally tyrannical … Our lives seemed to them a paradise which we had done nothing to deserve.”

Not exactly. As Leader points out, Bellow was subjected to antisemitic obscenities and insults shouted by French Canadian schoolboys.

Bellow was three when Abraham moved the family to St. Dominique Street in Montreal. Joseph, the protagonist in Dangling Man, was raised on St. Dominique (where I lived for a while as an infant). Like many Jewish boys of his generation, Bellow spoke to his parents in Yiddish and studied Hebrew. At the age of six, he entered Devonshire School (which I also attended).

In 1923, finding himself in trouble with the law following a stint as a bootlegger, Abraham brought his family to Chicago. Thanks to a cousin, he found employment in a bakery on the night shift. The Humboldt Park neighborhood in which they lived was ethnically diverse. Originally German, it was now inhabited by Poles, Scandinavians, Ukrainians and Jews.

At 18, Bellow enrolled at the University of Chicago, determined to be a writer. As Bellow recalls, his father, a practical man, could not “readily explain to his friends just what I was doing at the university, and perhaps he resented the embarrassment I caused him.”

In 1935, he transferred to Northwestern University, and there he wrote stories, mostly character sketches. His first published story, The Hell It Can’t, a 1,300-word piece, appeared in the student newspaper on February 19, 1936.

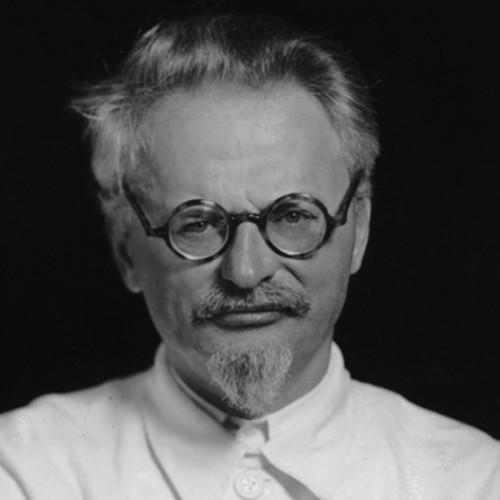

Politically on the far left, Bellow was a Trotskyist during his university days. On a trip to Mexico in 1940, he was given the opportunity meet the exiled Soviet leader Leon Trotsky in Mexico City. But on the day of their meeting, Trotsky was assassinated. “He was covered in blood and bloody bandages and his white beard was full of blood,” Bellow wrote after seeing his lifeless body in a hospital.

Bellow, who became a U.S. citizen in 1943, joined the Merchant Marine in April 1945, a month before the war in Europe ended. By then, having married the first of his five wives and having sired a son, he had published his first novel.

Alfred Kazin, his contemporary and the literary editor of The New Republic, was impressed by him. “He carried around with him a sense of his destiny as a novelist that excited almost everyone around him,” he observed. “Bellow was the first writer of my generation … who talked of Lawrence and Joyce, Hemingway and Fitzgerald, not as books in the library but as fellow operators in the same business.”

Through connections, Bellow began writing book reviews for The New York Times. On the recommendation of Time film critic James Agee, he got a job interview with Whittaker Chambers, who edited the magazine’s books and arts pages and who would be later unmasked as a Soviet spy. The interview was a disaster, says Leader.

Bellow continued to write, but his second novel, The Victim, sold a miserly 2,257 copies, only about 700 more than Dangling Man. Undaunted by their poor reception, he persevered, winning new admirers and much acclaim in his next four novels.

Due to his command of Yiddish and his understanding of shtetl culture, Bellow translated Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story, Gimpel the Fool, into English. It appeared in the May-June 1953 issue of Partisan Review and established Singer in the wider world.

Leader devotes several hundred words to Bellow’s visits to Israel. He skims over his encounters with the Israeli novelists S.Y. Agnon and Amos Oz and tells us nothing about Bellow’s view of Israel and Zionism.

He ends the book on an ambivalent note. Bellow is internationally acclaimed, having won his struggle to be recognized as a writer. But his personal life is in turmoil.

I eagerly await volume two of The Life of Saul Bellow.