Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian activist at Columbia University in New York City, has caused a furor and ignited a controversy. His case has triggered an impassioned debate about the limits of free speech and the boundaries of political activism.

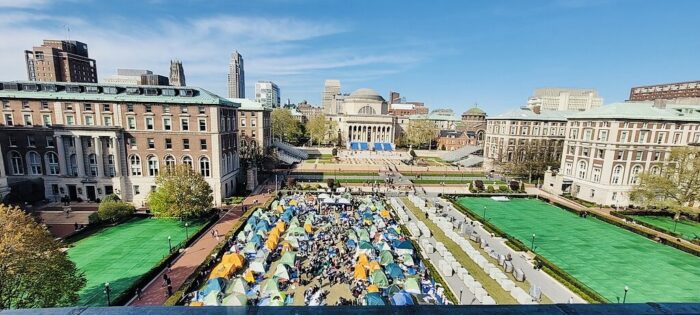

A 30-year-old Algerian national, a permanent resident of the United States, and a recent graduate of Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, he played a central role in the creation in 2024 of the “Gaza solidarity” encampment at Columbia, the first such encampment in North America.

More recently, he participated in a pro-Palestinian demonstration at Barnard College, the women’s school affiliated with Columbia.

Khalil is also a leader and a spokesman of an anti-Israel outfit known as Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD. It has urged the university to withdraw its investments from Israel, hailed Hamas — a designated terrorist movement — as a national liberation organization, and called for “armed resistance” against Israel.

CUAD’s unreasonable demand, its radical political positions and its disruptive tactics have galvanized its enemies and placed Columbia under stress and the threat of financial ruin.

A complaint filed against the university by Jewish students and Jewish organizations contends that the anti-Israel atmosphere generated by CUAD has been toxic: “Jewish and Israeli students have been spat at, physically assaulted, threatened, and targeted on campus and social media with epithets such as ‘death to Jews,’ ‘Zionist pig’ and ‘baby killer.”’

Earlier this month, Khalil was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers, charged with supporting terrorism and violating President Donald Trump’s executive order prohibiting antisemitism.

Trump applauded Khalil’s detention, calling it “the first arrest of many to come.”

Khalil, who has been ordered to be deported, is currently detained at the LaSalle Detention Center in Jena, Louisiana. District Judge Jesse Furman recently delayed his deportation so that he can study his case in a judicial review.

Khalil, whose Palestinian American wife is expected to give birth next month, was born in Yarmouk, a Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus. Khalil’s grandparents lived in a village near the Israeli city of Tiberias before fleeing to Yarmouk as refugees during the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948.

When I visited the camp in 1975 in my capacity as a journalist, the local guide warned me that its inhabitants would likely “drink my blood” if they knew I was Jewish.

Khalil’s supporters, who are fervently pro-Palestinian and perceive Israel as an artificial colonial construct, regard his detention as an assault on the First Amendment and an attempt to suppress pro-Palestinian views. Some liberal and progressive Jewish groups and leaders have voiced alarm over the arrest of a lawful U.S. resident on the basis of his opinions and activism.

His detractors, including the Anti-Defamation League, have praised Khalil’s arrest as a sign that the Trump administration is taking campus antisemitism and support for terrorism seriously. Trump, they argue, is following through on his presidential campaign pledge to deport student activists accused of endorsing terrorism and/or promoting antisemitism.

Trump administration officials, including Trump himself, have not precisely defined the meaning of antisemitism. But Trump’s unprecedented crackdown meshes with his promises to stand in solidarity with American Jews, to combat “anti-American” behavior on university campuses, and to deport non-citizens living in the United States illegally.

To no one’s surprise, Khalil denies he is an antisemite.

“As a Palestinian student, I believe that the liberation of the Palestinian people and the Jewish people are intertwined and go hand-by-hand, and you cannot achieve one without the other,” he told CNN last spring, implying that he espouses a binational state, rejects a two-state solution, and will only be satisfied once Israel is gone.

Responding to accusations that he and some of his supporters are guilty of antisemitism, he countered that there is “no place for antisemitism” in Palestinian activism. “Our movement is for social justice and freedom and equality for everyone,” he added.

Khalil’s deportation order, though the first of its kind related to pro-Palestine activism, is not entirely unique in the annals of American history.

In 1919 and 1920, during President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, the Justice Department arrested thousands of suspected anarchists and communists, some of whom were Jewish. The raids were supervised by Attorney General Mitchell Palmer. Nearly 600 out of some 6,000 suspects were ultimately deported.

More than a century on, Khalil faces a similar problem. Although he has not been charged with a crime, he finds himself in the crosshairs of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which enables the U.S. secretary of state to expel a person whose presence is incompatible with American foreign policy.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who personally ordered Khalil’s detention, has said that the government intends to deport Khalil, a Green Card holder. Rubio has denied that the issue of free speech is relevant in this instance. “No one has a right to a student visa,” he said. “No one has a right to a Green Card.”

The deputy secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Troy Edgar, has said that Rubio can review Khalil’s visa process at any point and revoke it.

In the meantime, the Trump administration is withholding $400 million in federal grants and contracts to Columbia University unless it implements sweeping changes.

Trumps demands are clear.

The university must immediately place its Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies Department under “academic receivership for a minimum of five years.” The university must ban masks on campus to conceal the wearer’s identity “or intimidate others.” The university must adopt a new definition of antisemitism, abolish its current process for disciplining students, and deliver a plan to “reform undergraduate admissions, international recruiting, and graduate admissions practices.”

“We expect your immediate compliance with these critical next steps,” officials from the Department of Education, General Services Administration and Department of Health and Human Services wrote.

Last week, the Education Department announced that it was investigating more than 50 universities, including major public universities, over alleged racial discrimination.

Columbia has already penalized students who illegally occupied a campus building last spring. CUAD has disclosed that 22 students have been expelled, suspended or had their degrees revoked. Among them were Grant Miner, an anti-Zionist Jewish student, and Aidan Parisi, a pro-Palestinian activist.

The proceedings against Khalil appear to have had a domino effect.

A day after his arrest, the Department of Homeland Security announced that Leqaa Kordia, a Palestinian from the West Bank who had taken part in a pro-Hamas demonstration at Columbia last April, had been arrested for overstaying a student visa that was terminated in 2022.

Ranjani Srinivasan, a Colombia graduate student from India who was involved in pro-Palestinian activities, left the United States voluntarily.

The secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Kirsti Noem, was pleased to see her go. “It is a privilege to be granted a visa to live and study in the United States of America,” she said. “When you advocate for violence and terrorism that privilege should be revoked, and you should not be in this country.”

A lot of Americans would agree with her stark appraisal.