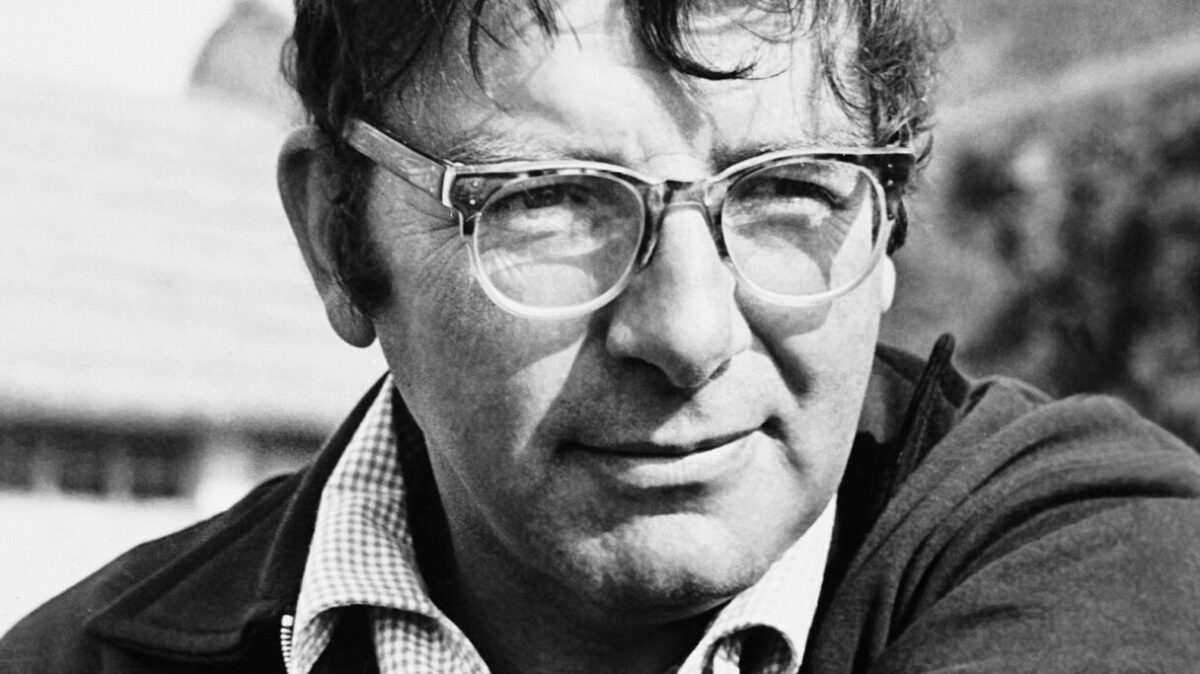

Cyril (Cy) Endfield, an American movie and theater director, will be remembered for his intense action dramas and his flight to Britain to rebuild his shattered career after he refused to cooperate with a U.S. congressional committee investigating purported communist influence in the Hollywood film industry.

Nearly thirty years after his death, Endfield’s star has faded, but his status as a master of film noir productions that explored the dark undercurrents of American society remains undimmed.

His disrupted but distinctive career is methodically examined by Brian Neve in The Many Lives of Cy Endfield (The University for Wisconsin Press), which is based on archival research and personal interviews.

A second generation American, a former communist and a blacklisted exile, Endfield carved out a name for himself in five films — The Argyle Secrets (1948), The Underworld Story (1950), The Sound of Fury (1950), Hell Drivers (1957), and Zulu (1964).

And in his role as a B-film auteur, he directed films inspired by the Dead End Kids and the Joe Palooka comic strips.

In the early 1950s, the producer Sol Lesser hired him to direct one of his Tarzan movies, Tarzan’s Savage Fury, which was crafted in a Culver City backlot and relied on wildlife footage stock as jungle backgrounds.

Endfield was born in 1914 in Scranton, a gritty town in northeastern Pennsylvania which had attracted Welsh, Italian and Polish immigrants. His father, Benjamin, a tailor from Lodz, Poland, immigrated to the United States in 1906.

The first of three children, Endfield was a bright student who developed an early interest in theater. Thanks to a scholarship, he attended Yale University, where he joined a theater group and the Young Communist League. Upon graduation, he earned a living as a magician and as the social director of a Jewish summer camps in the Catskills.

Neve, a British scholar, believes he was drawn to film in 1938. As Endfield wrote in a letter, “I have a predilection for movie direction quite divorced from the glamour attraction of Hollywood.”

Endfield spent about fifteen months in Montreal in that year, working for the Montreal Theater. He described it as “the only progressive organization in semi-fascist Quebec,” a province whose premier, Maurice Duplessis, was instrumental in the passage of the restrictive Padlock Law, which was aimed against communists.

Neve claims that Montreal was something of a turning point in his life. It honed his skills as a director, and it was where he met the first of his two wives, Fanny Shurack, an actress and comedienne who would change her surname to Osborne after they moved to Los Angeles in 1940.

Due to a chance meeting with the director Orson Welles, Endfield landed an apprenticeship at the Mercury Theater. The gig lasted only two months, but Welles sugarcoated Endfield’s disappointment by giving him a temporary job researching and drafting a script for one of his radio broadcasts.

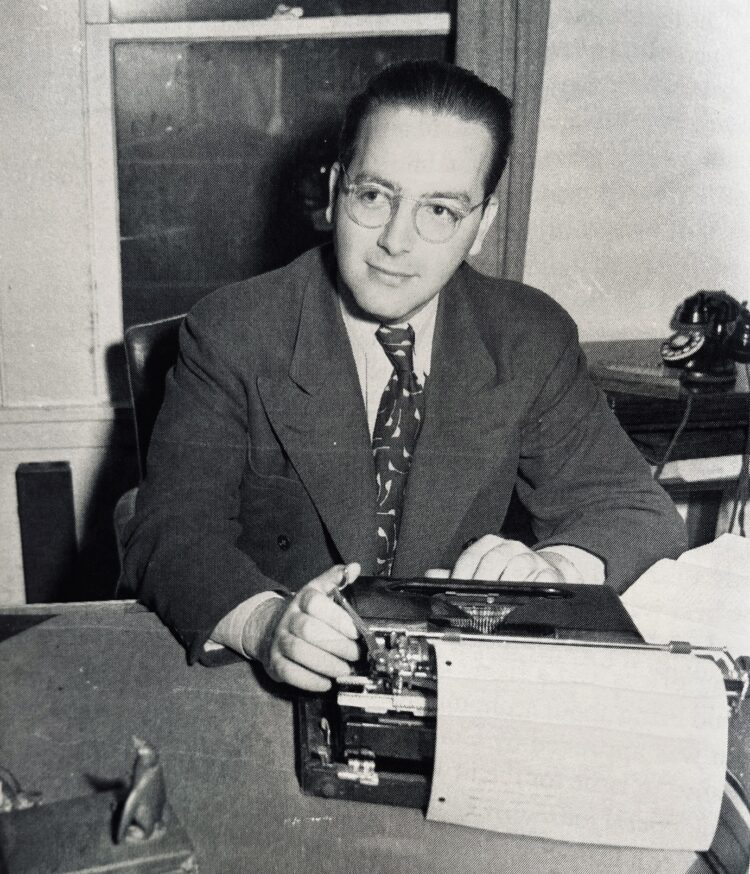

The Office of War Information handed Endfield his first assignment as a movie director. His documentary, Inflation, a short on the social dangers of the rising cost of living, was withdrawn from circulation on the day of its release because the Chamber of Commerce considered it an assault on capitalism.

At around this time, he began attending meetings of the Communist Party. His apparent infatuation with communism was short-lived. By 1948, he had left the party, but his association with it would cause him heartache.

Neve describes the period from 1949 to 1951 as one in which his profile was on the rise. By then, he had finished The Argyle Secrets, a low-budget, 64-minute film shot in only eight days starring William Gargan as a reporter who learns that Nazi sympathizers in the U.S. profited from World War II by collaborating with Germany.

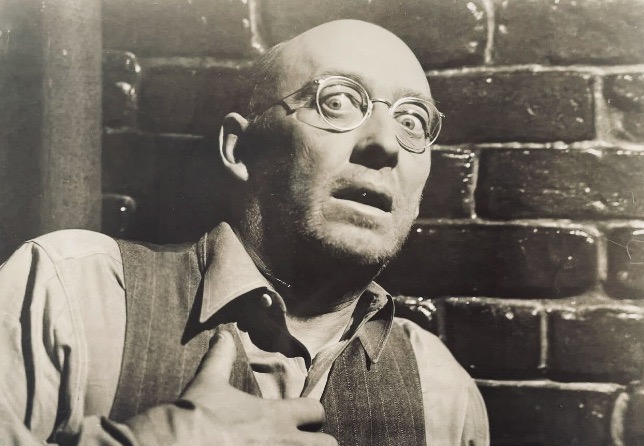

He followed this up with The Underworld Story and The Sound of Fury, the latter of which which Film Daily hailed as “a brilliant achievement.” The first film revolved around an unscrupulous journalist and the second one was about a financially-strapped man who descends into purgatory. Hell Drivers, gritty to the core, centers on long-haul truck drivers exploited by the shady company that employ them. Its cinematographer, Geoffrey Unsworth, would go on to shoot 2001: A Space Odyssey and Cabaret.

These films, suffused with pessimism, cynicism and greed, focus on volatile characters given to wrong-doing and brutality.

Much to his distress, he was named as a Communist Party member in September 1951, at the height of the McCarthyist witch-hunt. Rendered unemployable by Congress’ House Un-American Activities Committee, he fled to Britain several months later. Once in London, he informed the U.S. embassy that he was no longer a communist and had no intention of rejoining the party.

Eventually, Endfield found work in his adopted homeland and directed movies for Rank and Pinewood, the biggest studios in Britain.

Having been blacklisted due to his refusal to name names of suspected communists in Hollywood, he decided to cooperate with the congressional committee that had tarnished his reputation. After being cleared, he was free to work in the United States again. By that point, the notorious blacklist was crumbling. One of its victims, the screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, received credits for Otto Preminger’s Exodus and Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

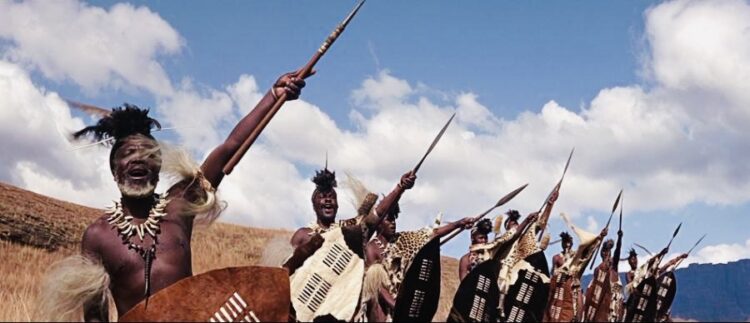

As Neve suggests, Zulu was one of Endfield’s most successful films. Inspired by a 19th century battle between Zulu warriors and British colonial soldiers, it made him a “bankable” director. Nevertheless, his final films, Sands of the Kalahari, De Sade and Universal Soldier, were essentially flops.

Neve has written a comprehensive account of an almost forgotten figure in American and British cinema. The Many Lives of Cy Endfield resurrects him and brightens his legacy.