It is arguably the most influential book of the 20th century. It is certainly the most notorious. Should it be able to circulate freely, or is it simply too toxic? And in the era of the internet, can a ban on its publication even work?

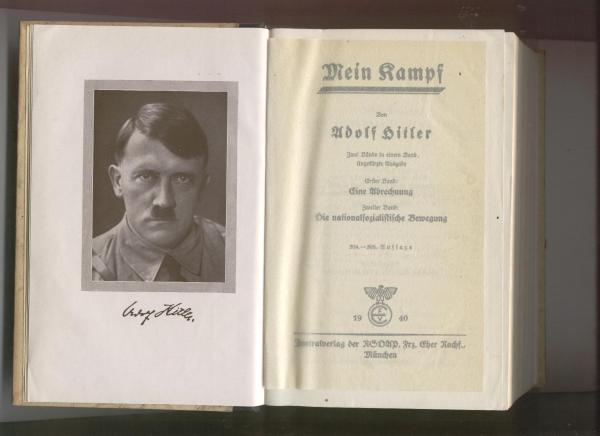

The book is Mein Kampf; the author, Adolf Hitler.

The book has been suppressed in Germany since the end of World War II, because its copyright holder, the state of Bavaria, has allowed virtually no legal versions to be produced since 1945. But Bavaria’s copyright expires at the end of 2015; after that, anyone can publish the book.

Since it will likely become available, the Institute for Contemporary History, a center for the study of Nazism in Munich, plans to produce an annotated “critical edition.” It is scheduled to appear the moment copyright expires on New Year’s Day, 2016.

The book’s extensive notations, notes historian Christian Hartmann, part of the editorial team, will “encircle” Hitler’s story line with a “collage” of commentary to demystify and decode it.

Mein Kampf (My Struggle) is the autobiographical manifesto by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, in which he outlined his political ideology and future plans for Germany. Volume 1 was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926.

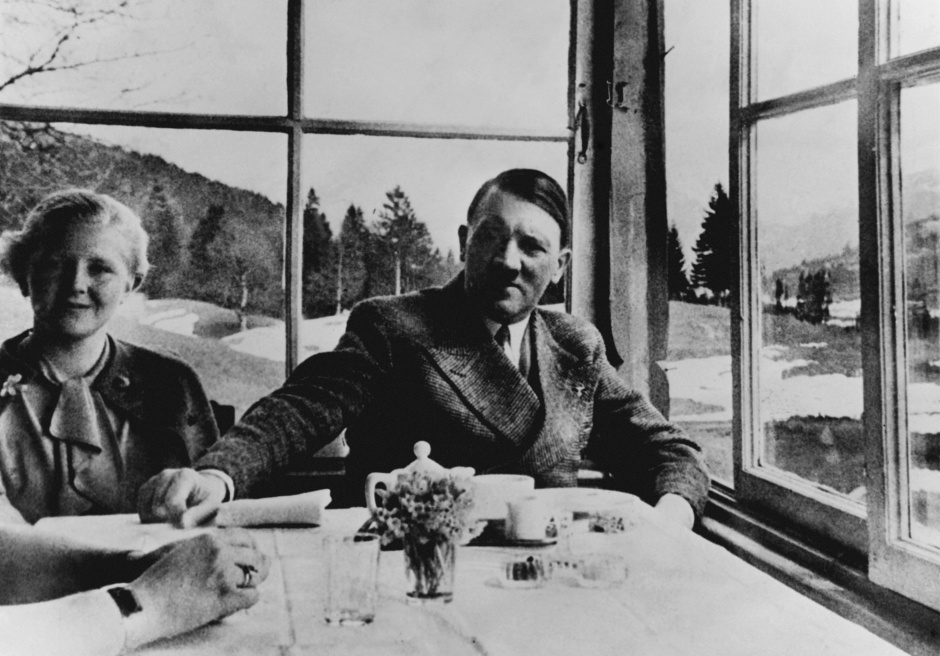

Hitler dictated it to fellow Nazi Rudolf Hess while in his cell in Bavaria’s Landsberg Prison in 1923-1924, where he had been incarcerated following the abortive Munich “Beer Hall Putsch” of Nov. 8, 1923 — his first attempt to take power in Germany — and later at an inn at Berchtesgaden.

When Mein Kampf was first released it fared poorly. However, after Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, 12 million copies were sold. A special edition, known as the Jubilaumsausgabe, or Anniversary Issue, was published in 1939 in honor of Hitler’s 50th birthday.

The book outlined Hitler’s world-view. He described the struggle for world domination as an ongoing racial, cultural, and political battle between the so-called “Aryans” and Jews, accusing the latter of conducting an international conspiracy to control world finances and the press, and inventing liberal democracy as well as Marxism and Bolshevism.

As the master race, the Aryans, he contended, were entitled to acquire more land for themselves. This Lebensraum, or living space, to the east of Germany, would be acquired by force, and would be used to provide room for the expanding Aryan population at the expense of the Slavic peoples, who were to be removed, eliminated, or enslaved.

Hitler saw himself as a savior of the human race from a plague, a disease, and fancied himself a profound thinker. Hitler’s Philosophers, recently published by historian Yvonne Sherratt, examines Hitler’s enthusiasm for philosophy and the thinkers in the field who prefigured and fueled his ideological leanings.

She writes of Hitler’s self-conception as the “philosopher-fuhrer.” Hitler had a dream to rule the world, not only with the gun but also with his mind, she contends. In turn, philosophers like Martin Heidegger embraced Nazism with apparently complete enthusiasm.

As the world well knows, Mein Kampf did indeed provide a blueprint for the horrors to come, including the organized genocidal murder of millions of innocent victims during World War II.

As Ron Rosenbaum has noted in the “Afterword” to the 2014 edition of his book Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil, Hitler “was using genocidal means to re-sculpt the human genome by carving off entire chunks,” including Jews, Roma, Slavs, and Soviet prisoners of war.

The debates over the “true nature” of Hitler may never come to rest. But should his pernicious and evil doctrine, as expounded in Mein Kampf, a book which may indeed seduce new generations, be made easily available in Germany?

Even among Jewish leaders, there are differences of opinion.

Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, contends that, as “the blueprint for the extermination of six million Jews and millions of others in the Holocaust,” it is “therefore an essential document to help Germans understand their history, even at the risk that neo-Nazis and haters could also use the book to promote a sinister agenda.”

On the other hand, Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress, feels that publishing it in Germany again at a time of rising antisemitism would be a travesty. “What would the Holocaust survivors and their relatives think if they visit a German bookstore and see Hitler’s book on the shelves?”

The Jews of Bavaria remain resolutely opposed. Charlotte Knobloch, a vice president of the European Jewish Congress and of the World Jewish Congress, and one of the primary leaders of the Jewish community in Munich, remarked that “Mein Kampf is the ideological foundation for the Holocaust. We should sink it in a very deep ocean so that it will never be seen again.”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.