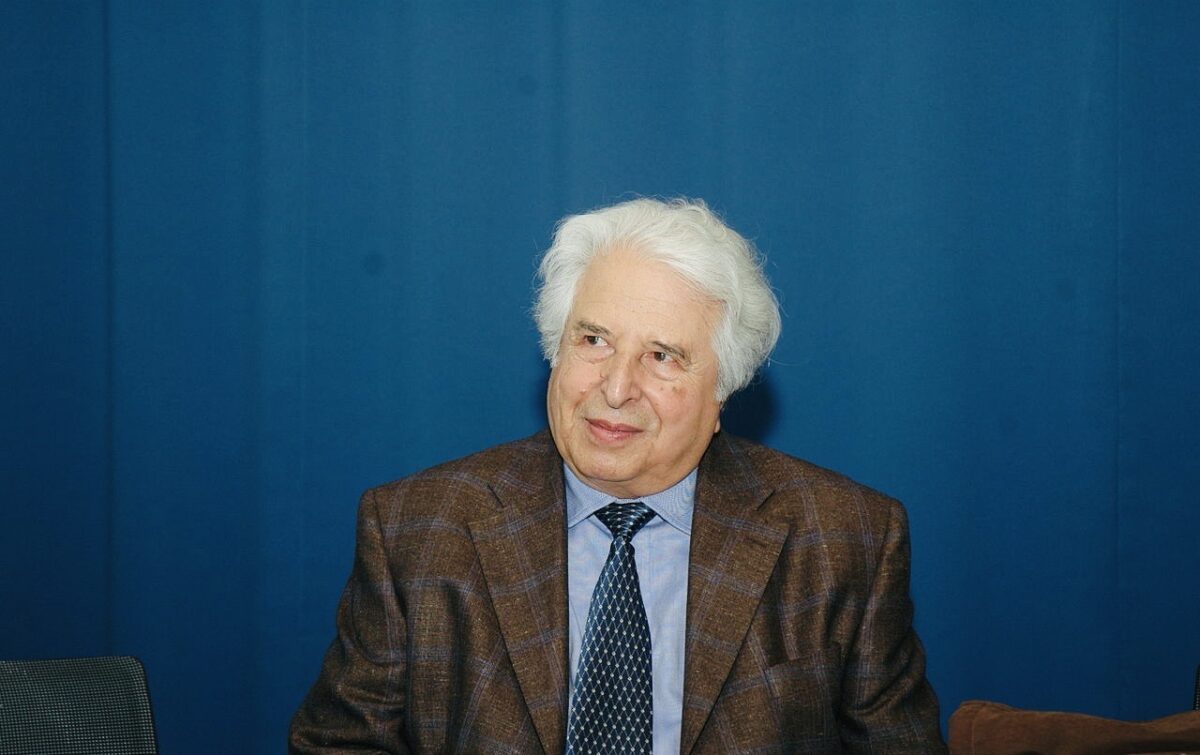

Saul Friedlander, the eminent historian, is a child of the Holocaust whose passage from adolescence to adulthood was marked by enormous turbulence and change.

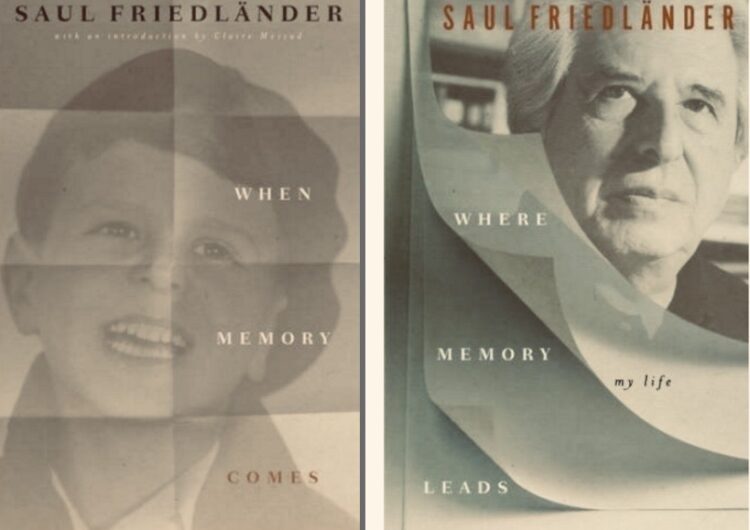

In his lucid, thought-provoking memoirs, When Memory Comes and Where Memory Leads, both published by Other Press in a paperback edition, he recalls pivotal events that shaped him to the core.

By the age of 16, as the novelist Claire Messud observes in the introduction, Friedlander had experienced “more trauma, upheaval and grief than many do in a lifetime.”

Born in Prague in 1932 into an assimilated, German-speaking middle-class Jewish family, he was originally known as Pavel. When the Friedlanders fled to France in 1939, he was renamed Paul. When he went to Israel in 1948, he Hebracized his name to Shaul, the French transliteration of which is Saul.

“I was born … at the worst possible moment, four months before Hitler came to power,” he writes.

Friedlander’s parents, Hans and Elli, were “non-Jewish Jews,” as the historian Isaac Deutscher would have aptly described them. So much so that they did not bother to have their son circumcised, a stroke of fate that may have saved his life.

Looking back at their values, Friedlander believes his father’s faith in assimilation was “mistaken.” He failed to recognize the Nazi danger, and his confidence in France was “ridiculous.”

“We should have been in Palestine or Sweden, like my uncles and grandmother, at least out of Hitler’s reach,” he adds. In the end, Friedlander muses, “my father was hunted down for what he had refused to remain: a Jew.”

Having left Czechoslovakia on the eve of World War II, the Friedlanders settled in Neris les Bains, a French spa. Friedlander was enrolled in a Jesuit boarding school, Saint-Beranger, under an assumed name, Paul-Henri Ferland. He disliked it with a passion. “Everything at Saint-Beranger stifled me: the austere discipline, the continual prayers … the dreariness of our dark building and, finally, the food, which seemed revolting to me.”

In the summer of 1942, his parents, with the assistance of Catholic friends, hid him in a seminary and then attempted to cross into neutral Switzerland. “They were arrested by the Swiss, delivered to the French, then to the Germans, transported to Auschwitz in November … and murdered.”

Not long afterwards he was baptized in the Church of Notre Dame in the town of Montlucon. “I soon felt a vocation. I wanted to become a priest.” He was intoxicated by the “austere simplicity” of mass, and he thought that the antisemitic Vichy regime was France’s salvation.

“I had passed over to Catholicism, body and soul. The fact that the misdeeds of the Jews were mentioned during Holy Week did not trouble me in the slightest.” Though conscious of his Jewish origins, he was a renegade who felt at ease in a community that had nothing but scorn for Jews.

For a while, he was a staunch Catholic, but after the war, he became a Communist and then a Zionist. “It would be hard for me today to point to any particular reason for this transformation,” he admits. But by the autumn of 1947, which coincided with the United Nations Palestine partition plan, Friedlander had committed himself to the Zionist cause

He joined the Betar youth movement, not having the faintest idea what it represented ideologically. In early June 1948, he boarded the Altalena, a Panamanian vessel which had been bought by American supporters of Menachem Begin’s Zionist Revisionist movement.

As the voyage ended, he writes, “Out of the darkness loomed up before us the land of Israel.”

Transporting arms and munitions for the Irgun, a right-wing militia at odds with the Israeli government, the Altalena reached Tel Aviv, where it was sunk by forces under the command of a young army officer named Yitzhak Rabin.

This unpleasant incident did not curb Friedlander’s enthusiasm for Israel. “Everything seemed a miracle to me: the local chocolate as much as the Jewish state itself.”

After spending several months with his uncle in Nira, a village near Netanya, he went to school in Ben Shemen, where he learned Hebrew and discovered the rudiments of Jewish culture. He then enrolled in a high school in Netanya.

Freielander adapted successfully to his new home. “I was my high school’s valedictorian, worked as a messenger boy at the Foreign Ministry, became a civilian employee in the army for six months, then served … in a highly secret intelligence unit for another two and a half years.”

Despite his attachment to Israel, he was drawn back to France. “My cultural identity has remained essentially French throughout my life,” he explains. “I fell in love with the sheer beauty of the French language.”

Having finished three years of evening classes at the Tel Aviv School of Law and Economics, he was accepted as a second-year student at a major university in Paris. During this interregnum, he worked in the Israeli embassy’s press department, where he befriended several Israelis who would achieve prominence in diplomacy, politics and journalism.

Harvard University accepted him as a graduate student in Middle Eastern politics and history, but Friedlander gave it up in 1958 to be the personal assistant of Nahum Goldmann, the president of the World Jewish Congress. He remained there for the next two years, shuttling between the United States and Israel. During this period, he met his first wife, an Israeli pianist.

In 1960, a friend introduced him to Shimon Peres, Israel’s deputy minister of defence, who hired him as an assistant. Friedlander spent the bulk of his time monitoring the construction of Israel’s nuclear reactor in Dimona.

Shifting to academia, Friedlander became a lecturer at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva. In the future, he would teach at two universities in Israel and at the University of California in Los Angeles.

Shortly after the end of the Six Day War, he was offered a one-year guest professorship in history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Israel by then had changed. “Israel revelled in an entirely new sense of power,” he says, referring to its victory in the war and its acquisition of Arab territories. “Occupiers and occupied were happily coexisting — or so it seemed.” His nonchalant attitude gave way to concern that Israel had bitten off more than it could swallow.

“During those early postwar years what I and others started questioning was not the principle of defensible borders but, under Golda Meir’s watch, the refusal to respond to any positive initiative coming from the other side … I started participating regularly in public meetings against the occupation and often expressed myself rather bluntly.”

On the other hand, he soon grew weary of the “dogmatism of the extreme left, by what I considered their total misunderstanding of Nazism and fascism, tags they applied so easily to the existing democratic systems, either out of ignorance or bad faith.”

In particular, he took issue with the Palestinian American academic Edward Said, who rejected a two-state solution and advocated the right of return of Palestinians refugees to their original homes in Israel. “To me, this was completely unrealistic.”

Nonetheless, Friedlander was confounded by Israel’s hubristic attitude toward the Arab world and by its “foolish sense of superiority and super-confidence.”

To his profound disappointment, Peres, as defence minister, tacitly supported Jewish settlers from Gus Emunim, whose goal was to tighten Israel’s grip over the West Bank.

A two-state solution supporter, Friedlander is of the view that the expansion of settlements in the West Bank must end and that Israel must be prepared for “difficult concessions.”

Friedlander began teaching at Tel Aviv University in 1976, and remained there for two decades.

During the 1980s, he spent much time in West Germany, where he felt both very much at ease and on edge. His trips to Berlin, in particular, convinced him to focus his scholarly attention on the Holocaust. In 1987, he was appointed the first permanent incumbent of the University of California’s Chair in the History of the Holocaust.

From 1990 to 2006, Friedlander wrote the first and second volumes of The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 2008.

Retiring in 2011, he considered the possibility of returning to Israel, whose energy and creativity he admires. He stopped short of taking the plunge, repelled by Israel’s tangible rightward drift. He feared that “the political environment would quickly become unbearable, even within the bubble of sanity that Tel Aviv appears to be.”

In closing, Friedlander dwells on this contentious issue.

“Criticizing Israel’s policies is not only justified, it is necessary. However, questioning Israel’s right to exist is a very different matter. Sometimes, one gets the feeling that, in the American academic environment, the first attitude leads to the second one. As for the second attitude, it often smells of more than a whiff of antisemitism.”

Given his tortuous life journey, Friedlander is obviously highly sensitive to such matters.