The Middle East has been convulsed by unprecedented spasms of violence in the past few weeks, and to no one’s surprise, Iran and its proxies have been at the center of this ongoing turbulence.

Amid the Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip and a low-intensity war pitting Israel against Hezbollah in and around Lebanon, clashes have broken out throughout the region, sparking speculation whether a regional war has not already erupted.

Iran, the preeminent Shi’a Muslim state and the instigator of the most recent problems, has fired long-range missiles at Syria, Iraq and Pakistan, stood shoulder to shoulder with the Houthis in Yemen, and extended unconditional support to Hamas and Hezbollah, both of which belong to Iran’s so-called “axis of resistance.”

To say that the Middle East is in turmoil would be an understatement.

Pro-Iranian surrogates have launched rockets at a U.S. army base in Iraq. Houthi rebels have continued to attack commercial shipping in the Red Sea despite U.S. retaliatory raids. Key figures in Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps have been killed by a rocket strike in Damascus widely attributed to Israel. Iran, which has sought to remind rivals that it is a regional power and can strike adversaries at will, has vowed vengeance, ensuring that yet more chaos will descend on the Middle East.

The latest cycle of regional bloodshed was set off by a massive explosion in Iran on January 3, when Islamic State terrorists detonated two bombs in the city of Kerman, killing 88 people. Regarded as the worst suicide bombing in Iran since the 1979 Islamic revolution, it rattled the Iranian government to its core.

The attackers in Kerman bombed a memorial event in honor of Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’ Quds Force. Assassinated by a U.S. drone strike in Baghdad in 2020, he is seen as a hero and a martyr by the Iranian leadership.

At first, Iran predictably blamed its arch enemies, Israel and the United States, for his untimely death. But since then, Iran has tacitly acknowledged that Islamic State, which regards Shi’a Muslims as heretics, was in fact the culprit.

Thirsting for vengeance, and anxious to demonstrate strength both domestically and abroad in the face of internal challenges to its authority, Iran went on the offensive across the region.

Iran fired a barrage of missiles into a province in northwestern Syria still held by Syrian rebels opposed to the dictatorial regime of President Bashar al-Assad, a close Iranian ally. Iran announced that Islamic State bases had been struck in retaliation for the bombings in Kerman.

Analysts interpreted Iran’s strike as an unmistakable message to its foes that it is prepared to act far afield if necessary.

At around the same time, Iran launched precision-guided Kheibar Shekan missiles toward northern Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan region. Tellingly enough, the missile is named after a seventh-century battle during which a Muslim army defeated Jewish tribes in Arabia.

The Iranian strike, aimed at an Israeli “espionage center” in the city of Erbil, claimed the lives of a family in a building near the U.S. consulate. Iran claims that the Mossad maintains a station in Erbil, but Israel stoutly denies it.

In all probability, Iran’s missile attack was designed to avenge the assassination of an Iranian general, Sayyed Razi Mousavi, in Syria last month. Iran immediately blamed Israel for his death. Mousavi, a member the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, was reportedly responsible for the shipment of weapons and munitions to Hezbollah, a key ally/proxy of Iran and Israel’s deadly adversary.

Iran, too, may have been exacting payback for an Israeli missile strike which damaged a drone factory in Iran in 2022.

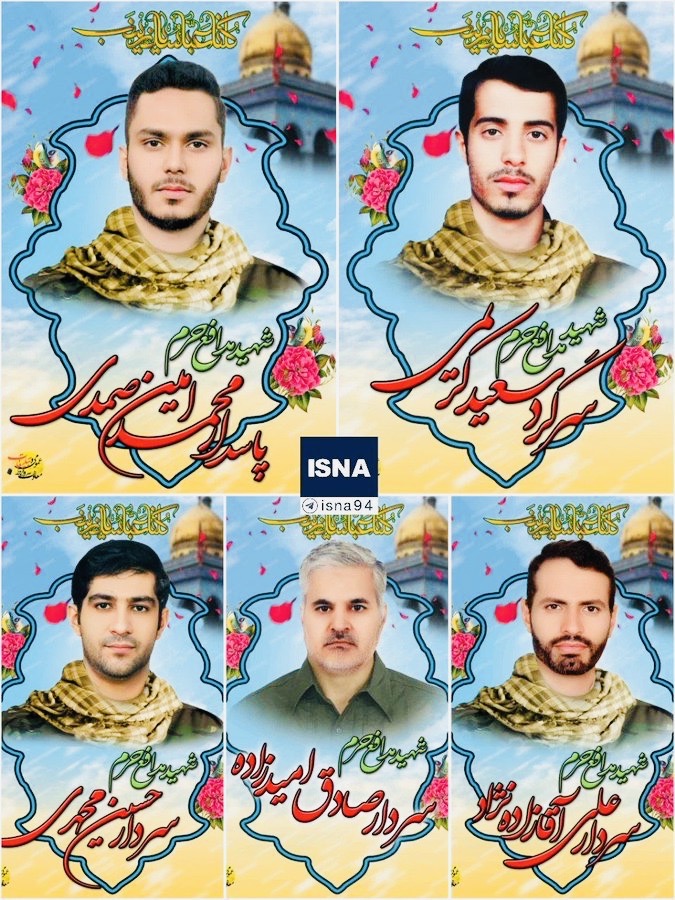

On January 20, Iran announced that five members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps stationed in Damascus, including a general and his deputy, had been killed by missiles strikes.

Hamas condemned the assassinations as a “heinous crime.” Iran’s Sepah news agency pointed a finger at the “evil and criminal Zionist regime.” Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi promised punishment, asserting that “the crimes of the Zionist regime” will not go unanswered.

On another front, far from the killing fields of Syria’s ongoing civil war, Iran lashed out at Pakistan, a normally friendly country. Acting in response to an attack by Baluchistan separatists on an Iranian police station in southeastern Iran on December 15 that led to the deaths of eleven officers, Iran struck Jaish al Adl bases in Pakistan, killing only Iranian nationals.

In a careful tit-for-tat reprisal, Pakistani jets bombed Baluch militants in Iran, killing nine, all of whom were citizens of Pakistan.

The air raid effectively ended Pakistan’s confrontation with Iran, with the Iranian government saying it “differentiates between Pakistan’s brotherly government and armed terrorists” and adding it would not allow them to “strain” their otherwise cordial relationship.

As Iran and Pakistan patched up their quarrel, pro-Iranian surrogates fired missiles at the Al-Assad U.S. military base in western Iraq. Several soldiers were wounded with traumatic brain injuries. Over the past few months, there have been 140 such attacks in Iraq and in neighboring Syria, injuring 70 troops. Iran, which maintains good relations with both countries, has encouraged these assaults in the hope of ousting U.S. forces from the Middle East.

At present, 2,000 and 900 American troops are respectively stationed in Iraq and Syria to combat lingering, ragtag bands of Islamic State fighters who yearn to reestablish the caliphate that was destroyed by U.S. Iraqi and Kurdish forces in 2017.

While the Iraqi government supports the U.S. mission on its soil, Syria — an ally of Iran and Russia and Israel’s foe — resents it and has demanded the complete withdrawal of American forces.

With Iran’s encouragement, the Red Sea, one of the most important commercial sea lanes, continues to be a battle zone, U.S. retaliatory air and missile strikes notwithstanding.

For two months now, the Iranian-backed Houthi militia, which controls much of Yemen, has attacked ships with drones and missiles. The Galaxy Leader, a tanker carrying new cars, was hijacked by the Houthis in November and towed to Yemen along with its crew of mostly Filipino sailors.

The Houthis have been targeting vessels partially or wholly owned by Israelis, or en route to the Israeli port of Eilat, in support of Hamas and in a bid to pressure Israel to end its military campaign in Gaza. In reality, however, they have attacked ships linked to more than twelve countries. Most recently, the Houthis declared that “all American and British ships” are potential targets.

In addition, the Houthis have launched several missiles toward Eilat, but they have been shot down by U.S. and Israeli forces.

As a result of Houthi aggression, scores of ships have avoided the Suez Canal, much to Egypt’s financial detriment, and instead have sailed around the Cape of Good Hope, a journey of an extra 6,400 kilometres miles around Africa which, inevitably, has inflated the cost of petroleum and household goods.

Since the Houthis pose a dire threat to the global economy, the United States has been drawn into the conflict inexorably. Until recently, the U.S. Navy countered the Houthis by shooting down Houthi drones and missiles before they could damage or sink ships. But this was not a cost-effective strategy, nor did it deter the Houthis.

For about the past ten days, the United States has been attacking Houthi missile launchers in Yemen, but these strikes have damaged or destroyed only up to one-third of the Houthis’ capabilities.

While President Joe Biden has admitted that U.S. airstrikes have not stopped the Houthis from attacking shipping in the Red Sea, he has said they will continue. But to what end?

It would appear that the United States will have no choice but to escalate its military campaign against the Houthis if it is to achieve tangible results.

Beyond that, the United States may soon have to decide whether it has the stomach to confront Iran itself, the head of the snake, the rogue country that constantly sows tension and destabilizes the Middle East through its obedient and skilled array of proxies.

Iran cleverly prefers to work through them while usually keeping its dirty hands clean, but the day may be approaching when this strategy will no longer be possible or feasible. If that moment of reckoning appears on the horizon, the Middle East likely will be thrown into yet further upheaval and uncertainty.

Critics claim the Biden administration has been too conciliatory toward Iran, but it rejects the argument, saying it has imposed sanctions on 500 Iranians, companies or government entities. “There’s been a lot of effort here to hold Iran accountable for their destabilizing activities,” White House spokesman John Kirby said on January 19 by way of explaining U.S. policy.

These efforts have neither impressed nor deterred Iran.