The Jews of Italy have survived four major plagues through the centuries — religious persecution, ghettoization, fascism and the Holocaust — and have endured.

Sara Reguer, the chair of the Department of Judaic Studies at Brooklyn College, relates their 2,000-year history in a cogent and deeply-researched book, The Most Tenacious Of Minorities, published by Academic Studies Press.

Few Jewish communities in the Diaspora are as old as the one in Italy, and that’s one of the reasons Reguer’s account is well worth reading. She takes us on a journey, full of promise, peril and renewal, that begins during the Roman empire and ends in present-day Italy.

It’s quite a trip.

As she points out, the first known Jews to settle in what is now Italy were international traders and craftsmen. They were followed by Jews from the Land of Israel who were brought to Rome as slaves and paraded in front of Roman throngs. These events, she reminds us, were later commemorated in the monumental Arch of Titus, now a tourist attraction.

Reguer claims the Romans treated Jews fairly, as citizens and as neighbors, but quickly adds that the Jewish residents of Rome were required to pay a special tax, which became the prototype of the levy imposed on European Jews during the Middle Ages.

In addition, Jews were prohibited from owning slaves and holding public office, restrictions which came into effect around 439 CE. Possibly because of these edicts, some Jews chose to convert to Christianity, a phenomenon that would recur again and again in reaction to antisemitic pressure and assimilation.

Benjamin of Tudela, a medieval Jewish traveller and scribe, toured Italy and noted that Jews occupied all strata of society but that the majority were involved in handicrafts.

The community expanded with the arrival of Jews from Germany and France in the 14th century. During the following century, Jews were permitted to live in a host of city states from Ferrara to Cremona, but Rome remained the center of Jewish life. Jews, including New Christians from Spain and Portugal, were permitted to settle in Venice, but behind ghetto walls. A papal bull issued by Pope Paul IV in 1555 further emasculated the Jewish condition.

With the unification of Italy in the last half of the 19th century, Jews were emancipated, except in the papal states and in territories under Austrian control. “Jews were now integrated successfully in Italian society,” writes Reguer, adding that they became psychologically and intellectually Italian. By then, Italy was home to some 40,000 Jews, comprising less than one percent of the population.

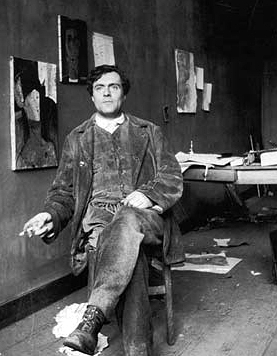

“There was broad participation of Jews in national life,” she says. “In politics, there was a Jewish mayor of Rome — Ernesto Nathan — from 1907 to 1913, and Jewish members of the senate and cabinet. And a Jewish man named Luigi Luzzatti became prime minister in 1909. In the arts, Italo Svevo and Alberto Moravia were famous Jewish authors, and Amadeo Modigliani was an Italian-Jewish painter and sculptor. Jews made up 8 percent of university professors, and they joined the army officer corps.”

By 1938, more than 10,000 Jews had joined Benito Mussolini’s fascist party. Claiming that Mussolini was not a racist, Reguer reminds a reader that his mistress for many years was Margherita Sarfatti, an art critic and co-editor of the party’s monthly ideological review.

As Mussolini drew closer to Nazi Germany, he turned antisemitic. Two anti-Jewish laws were passed between September and November 1938, and a third one was introduced in June 1939.

The Jewish reaction varied.

About 6,000 Jews emigrated. Three thousand converted to Catholicism. The remainder tried to adjust to the harsh reality of second-class citizenship.

Still, Jews in Italian-occupied Greece, Croatia and France were treated better than one might have expected.

Germany’s occupation of Italy proved fatal for 8,500 Italian Jews who were deported. Still other Jews were murdered by the Germans and their Italian collaborators. Yet about 80 percent of Jewish Italians survived. Some, of course, were helped by Christians, who sheltered Jews in monasteries and convents.

Summing up the Holocaust in Italy, Reguer observes: “There was a not a single Jew who was not affected, who did not lose family and friends, or who did not feel that their government, their neighbors and their countrymen had betrayed them.”

After the war, residential and commercial properties that had been seized from Jews were returned to their rightful owners. Also, the Italian government quietly aided Jews who had moved to Israel. “These unassuming activities were part of the reason why few or no reparations claims were made to the postwar Italian governments,” she explains.

In recent years, the community has been bolstered by Jewish immigrants from two Muslim states, Libya and Iran.

By her estimation, 25,000 Jews live in Italy today, with 13, 500 living in Rome. Smaller communities are found in Milan, Florence, Livorno, Trieste, Venice, Genoa, Naples, Bologna, Padua, Ancona and Pisa. “These numbers include only those Jews who identify themselves as such,” she says. “Should intermarried couples and their children be included, the number would grow exponentially.”

In conclusion, Reguer signs off with this succinct comment, “The number of Jews in Italy remains small, but (the community) is stubbornly maintained through the arrival of new Jewish groups seeking refuge. These are the latest communities to contribute to the Italian Jewish reputation as the most tenacious of minorities.”