It’s no secret that The New York Times, the preeminent daily newspaper in the United States, downplayed the Holocaust as it unfolded in real time in Europe. Scholars and journalists have written reams of articles and monographs about its abject and unforgivable sin of omission.

The Times’ failure was all the more shocking because it’s a newspaper of record, as its front page slogan, “all the news that fit to print,” blares.

Emily Harrold’s documentary, Reporting on the Times: The New York Times and the Holocaust, dredges up its pathetic coverage of this unprecedented atrocity.

Currently being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation, Harrold’s film, though only 18 minutes long, touches on the most important points and packs a punch. It was inspired by Laurel Leff’s book, Buried by the Times.

The statistics tell the story succinctly. From 1939 to 1935, the Jewish-owned Times published more than 23,000 front page stories. Nearly 12,000 concerned World War II. A mere 26 were about the Holocaust.

“It was a bad judgment call,” says Alex Jones, a former Times reporter.

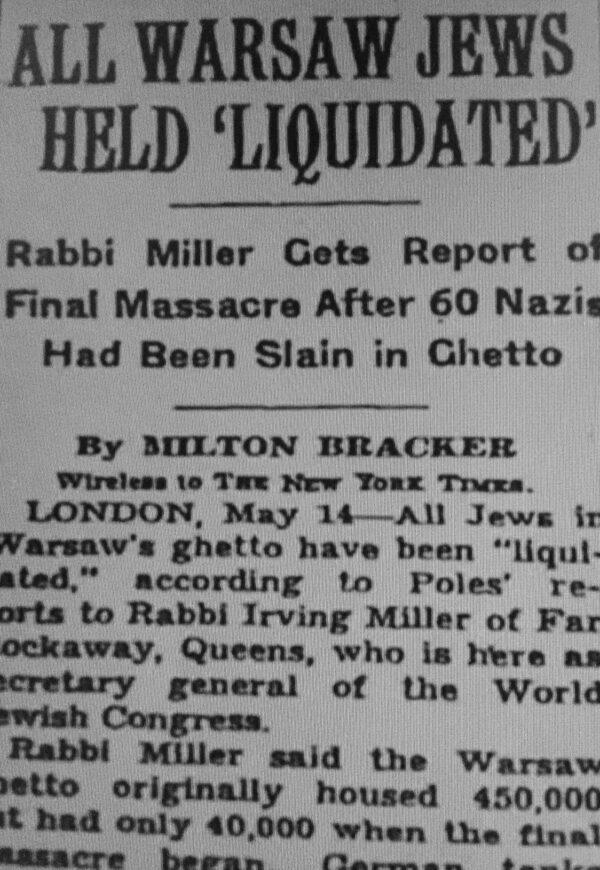

As Leff correctly observes, the Times usually buried stories relating to the Holocaust. The article it carried on the fall of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943 was placed on the bottom of page six. “The way the Times treated the destruction of the ghetto was emblematic of the way it treated the annihilation of the Jews,” she says in a stinging indictment.

American dailies took their cue from the Times, says former Times reporter Ari Goldman. As he puts it, “If it wasn’t in the Times, it didn’t happen.” As a result, the Holocaust was a disgracefully underplayed story.

“We kept hoping the world would know,” says Estelle Laughlin, a Holocaust survivor from Poland. “How could such horror not be questioned? It’s incomprehensible to me.”

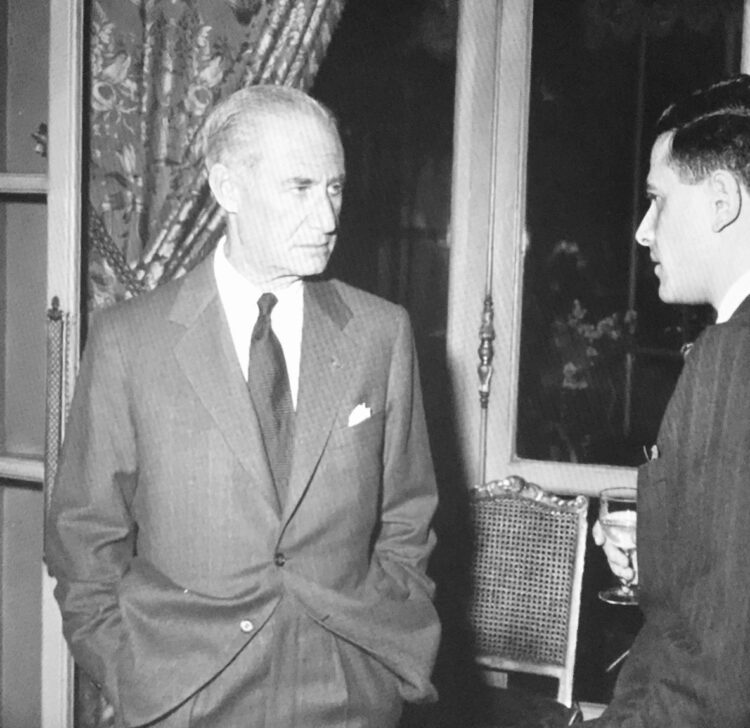

In fact, the rationale for the Times’ policy was crystal clear, at least to its publisher. Arthur Hays Sulzberger, an assimilated Jew, lived in fear of the Times being stigmatized as a “Jewish” newspaper.

Although he moved in elite ruling circles, Sulzberger was acutely conscious that antisemitism pervaded American society. As historian Hasia Diner points out, the majority of Americans harbored antisemitic notions and tropes.

“Antisemitism was a very serious factor in the United States,” New York City Rabbi Haskel Lookstein says. “It was not easy to be a front-and-center American Jew.”

This was a period when American antisemites like Charles Lindbergh and Father Charles Coughlin were quite influential in forming public opinion.

In addition, Sulzberger regarded himself as an American who happened to be Jewish. Since he believed that Judaism was a religion rather than a nationality, he could not relate to the plight of Jews in Europe.

The U.S. State Department minimized the severity of the Holocaust and opposed a mass influx of Jewish refugees into the United States. Sulzberger adopted its analysis and outlook. His attitude was reflected in the Times’ flimsy coverage of the Holocaust.

In 1996, the Times finally admitted its appalling mistake, but the cost of its journalistic shortcomings was catastrophic, as Harrold contends in her brief but bracing movie.