Early on the morning of October 7, 2023, Israeli soldiers guarding the border along the Gaza Strip noticed signs of an imminent attack. Around the same time, the head of the Israeli army’s Southern Command, General Yaron Finkelman, returned to his post after a vacation.

At 6:29 a.m., as several thousand enemy rockets began raining down on Israel, 3,000 terrorists breached the high-tech security fence and stormed into kibbutzim, towns and army bases in what Hamas labelled as Operation Al Aqsa Flood.

Unprecedented in its size, scope and destructiveness, it shattered Israel’s sense of security and triggered the Israel-Hamas war and, later, Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon.

Seth Frantzman, an Israeli journalist who covered the war, resurrects these momentous events in his engaging and usually absorbing book, The October 7 War: Israel’s Battle For Security In Gaza (Wicked Son), which unfolds lucidly in three parts.

The first is a backgrounder on Gaza. The second is a primer on Hamas’ rampage and Israel’s response. The third is a summary of the first five months of the war, which was paused recently by a tenuous six-week ceasefire agreement that may or may not endure.

As he correctly observes, Gaza has played a pivotal role in Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians.

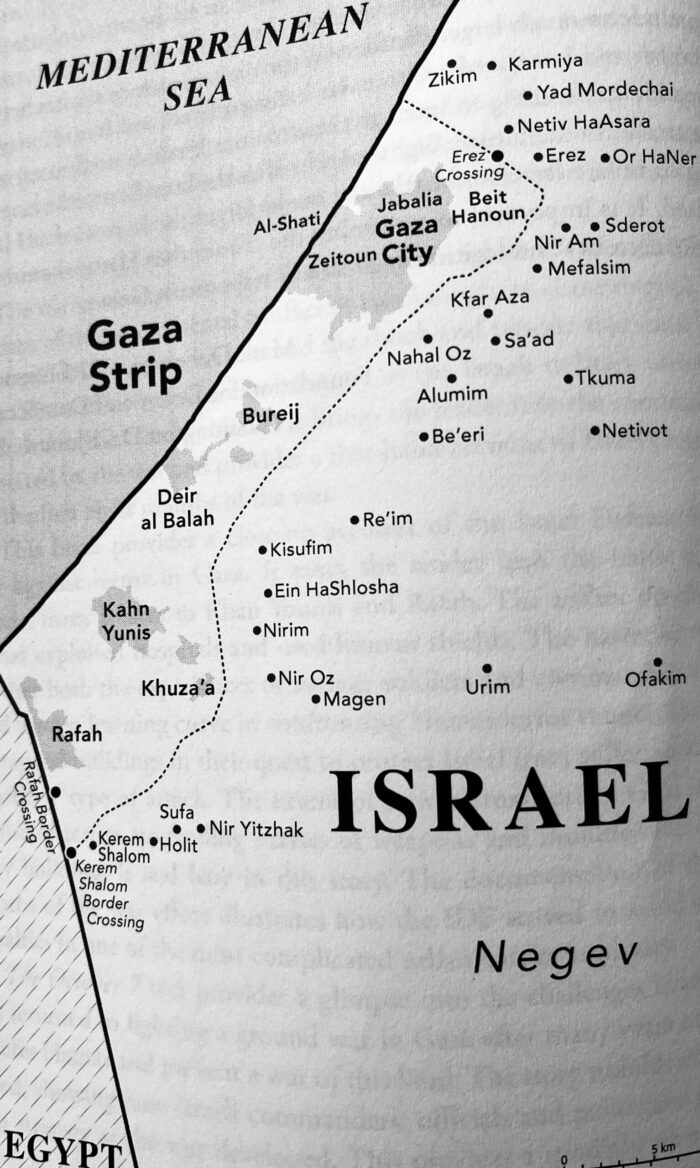

During the British Mandate period, the Zionist movement in Palestine built an array of settlements around Gaza ranging from Yad Mordechai and Nir Am to Nirim and Be’eri. The town of Sderot, just one kilometer away from Gaza, was founded in 1951.

Palestinians displaced by the 1948 war were resettled in eight refugee camps in Gaza, which would be incubators for terrorists. Due to a succession of wars, Israel occupied Gaza no less than three times. The first Palestinian uprising erupted in Gaza in 1987, when Hamas was created. Mohammed al-Dura, a Palestinian boy shot by Israeli forces in Gaza, became a symbol of the second intifada.

Hamas, having defeated the mainstream Fatah movement in a 2006 election in Gaza, staged a violent coup against the ruling Palestinian Authority in 2007. From that point forward, Hamas, an organization dedicated to Israel’s destruction, converted Gaza into an armed camp.

Hamas assembled an army, amassed an arsenal and constructed 600 kilometres of tunnels in anticipation of waging war against Israel. From 2008 to 2021, Hamas and its sister organization, Islamic Jihad, regularly bombarded Israel. These missile and mortar attacks sparked cross-border wars in 2008, 2011, 2014 and 2021. Frantzman describes these interrelated events clearly and concisely.

He reminds readers that Israel’s policy was to manage or shrink the conflict by buying off Hamas with infusions of dollars from Qatar. Convinced that Hamas was deterred and interested in developing Gaza, Israel focused its attention on the threats posed by Iran and the Lebanese militia Hezbollah, an Iranian proxy.

Despite its preoccupation with Iran and Hezbollah, Israel, in 2014, constructed a billion dollar border fence to keep terrorists at bay. Frantzman points out that defensive barriers, from the Maginot Line in France to the Bar-Lev Line along the Suez Canal, have not worked.

Israel’s fence was just as ineffective when it was put to the test. As he observes, the barrier was not intended to stop a massive attack, but to “prevent infiltrations and attacks by small groups of terrorists. As with most failures in military history, the fence was designed for the past war.”

Apart from this problem, he adds, Israel recklessly failed to station sufficient forces near Gaza. By his estimate, only 700 soldiers guarded the border on that fateful day in October. Soldiers normally assigned to the Gaza front had been transferred to the West Bank to guard Israeli settlements amid an upsurge of terrorism.

The Israeli government believed that Hamas, having been pummelled in previous wars, would abide by the status quo. Israel’s calculation was incorrect. Hamas, egged on by Iran, meticulously planned a war.

Hamas’ deception worked like a charm, luring Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu into a false sense of security. In what was a colossal intelligence failure, Israel got wind of Hamas’ plan in 2022, but failed to take it seriously.

During the initial hours of the war, Hamas fired 3,000 missiles at Israel. The massive barrage not only targeted a music festival near Gaza, but a string of cities from Beersheba and Kiryat Gat to Tel Aviv and Rishon Lezion.

On the first day, around 300 Israeli soldiers, including several high-ranking officers, were killed, as were 61 policemen and 38 members of security forces protecting kibbutzim.

According to Frantzman, women played an unprecedented role in defending the country. When terrorists broke into army bases, 15 female observers were killed and seven taken hostage.

Terrorists left behind scenes of carnage in many kibbutzim. In Sderot, they captured the police station. But in some places, such as Kibbutz Magen, they were decimated in a hail of bullets. Israeli drones and helicopters picked off others, but also accidentally killed Israelis.

The Israeli Air Force roared into action in Gaza immediately, bombing military targets but also civilian infrastructure commandeered by Hamas. Five army divisions were sent to the border, three were dispatched northward after Hezbollah opened fire on Israeli communities in the Galilee, and one was assigned to the West Bank.

Frantzman suggests that Israel was not entirely prepared to launch a full-scale invasion of Gaza. Its assumption was that there would be no need to capture Gaza.

Frantzman discloses that Israel relied on artificial intelligence to produce targets quickly and accurately. While Israel destroyed hundreds of tunnels and tunnel shafts, its attempt to flood them with sea water was only partially successful.

In passing, Frantzman devotes a few paragraphs to the Israeli Navy’s contribution. He delves deeply into the battles that raged in Gaza, but sometimes overwhelms a reader with a mountain of minute details.

Since Gaza is at the center of his book, Frantzman glosses over Israel’s low-intensity conflict with Hezbollah and its direct armed clashes with Iran.

In closing, he criticizes the Israeli government for having allowed Hamas and Hezbollah to build up their respective forces to an alarming degree prior to the war. And he critiques the Israeli army for having insufficient forces at its disposal when the war in Gaza erupted. He also disposes of the notion, promoted by Netanyahu, that Israeli military pressure would pressure Hamas to release the hostages.

One can safely assume that many more books will be written about Hamas’ attack and its aftermath. But in the meantime, The October 7 War serves as a fine introduction to the tumultuous events surrounding this massacre and the Gaza war that followed.