Shortly after World War II, the German philosophers Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno wrote in their book, The Dialectics of the Enlightenment, that antisemitism was no longer possible after the unprecedented horror of the Holocaust.

Six decades on, their thesis appears incredibly foolishly and profoundly naive.

What were they thinking?

After Auschwitz, antisemitism never vanished, and probably never will. As Daniel Jonah Goldhagen observes in The Devil That Never Dies (Little, Brown and Company), the longevity, tenacity, adaptability and range of antisemitism is unparallelled in history. It cuts across cultures, countries and continents and continues to be a pernicious and dangerous global phenomenon.

Likening antisemitism to the devil, Goldhagen, an American scholar whose previous work was Hitler’s Willing Executioners, reminds a reader that it has inflamed and perverted minds and hearts and unleashed calumnies, riots, pogroms, expulsions and mass murder, all in the name of a misguided and ignorant hatred.

“Antisemitism has moved people, societies, indeed civilizations, for two thousand years,” he notes in this hard-hitting and wide-ranging tour d’horizon.

But in the past 20 years, he adds, it has exploded in volume and intensity. As he puts it, “The upsurge had been so meteoric and the canards advanced so prejudicial that if anyone in 1990 or even 1995 had predicted the current state of affairs, he would have been seen as a fanciful doomsayer.”

The accusations levelled against Jews since time immemorial can fill a thick catalogue.

Jews are in league with the devil. Jews corrupt the moral fabric of societies. Jews seduce and defile Christian women. Jews are dishonest and crafty and care only about themselves. Jews are fifth-columnists. Jews corrupt art and culture. Jews are behind capitalism and communism. Jews are a race apart.

And the list goes on ad nauseum.

Goldhagen claims that antisemitism, in great measure, is eliminationist in character, threatening politically and physically Jewish communities around the world and jeopardizing Israel’s very existence.

The claim, in my view, is exaggerated.

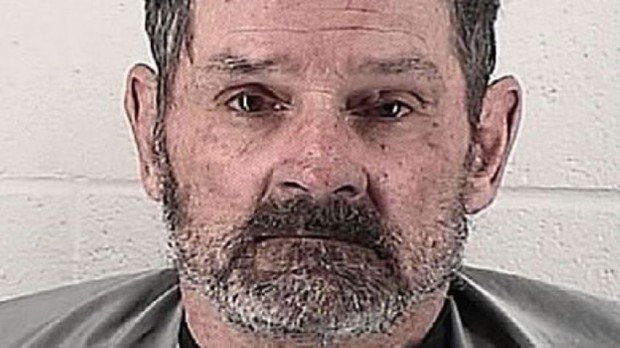

Only clinically unhinged and radical antisemites, like the American racist and white supremacist Frazier Glenn Miller, who shot and killed three people in front of a Jewish community center in Overland Park, Kansas, on April 13, would consider the physical destruction of Jews as a means to satisfy their perverted fantasies. But Goldhagen is basically right when he refers to antisemitism as a persistent pathology defying epochs and borders.

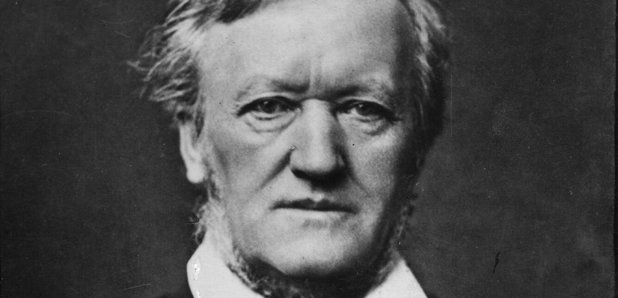

John Chrysostom, an early Christian theologian, set the tone in 386 AD in a series of eight homilies, Against the Jews. Peter the Venerable of Cluny, a medieval church leader, doubted whether “a Jew can be really human,” a concept the Nazis seized upon with glee. Martin Luther, the founder of Protestant Christianity, described Jews as “tricky serpents” and “the children of the devil.” Francois de Voltaire, the Enlightenment philosopher, stated, “The Jew does not belong to any place except that place in which he makes money.” Richard Wagner, the composer, claimed that Jews are an alien and corrosive element in music. T.S. Eliot, the poet, wrote, “The rats are underneath the piles/the jew is underneath the lot…”

More recently, the Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis, the Australian film actor/director Mel Gibson and the Portuguese Nobel Prize winning novelist Jose Saramago have contributed rants to the stinking, festering body of antisemitic literature.

“Everything that happens in the world today has to do with the Zionists,” Theodorakis blurted out in 2001. “Fucking Jews … the Jews are responsible for the the wars in the world,” Gibson exclaimed in 2006 after being stopped for drunk driving. “Israel, in short, is a racist state by virtue of Judaism’s monstrous doctrines,” Saramago wrote in an article published in the Spanish daily El Pais.

Antisemitism spiralled into disrepute in the wake of the Holocaust, the culmination of centuries of anti-Jewish prejudice. For a while, expressions of antisemitism were deemed beyond the pale and out of bounds, says Goldhagen. But as memories faded and repressed animosities re-surfaced, it roared back with a vengeance, gaining ground particularly in Muslim societies.

“Antisemitism is practically an article of faith … in much of the Arab and Islamic worlds,” he writes, citing a litany of trenchant examples.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the president of Iran from 2005 to 2013, was a Holocaust denier, the sole post-war head of state to deny the undeniable. Before he assumed the presidency of Egypt, Mohammed Morsi compared Jews to monkeys. Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, has been quoted as saying, “If we searched the entire world for a person more cowardly, despicable, weak and feeble in psyche, mind, ideology and religion, we would not find anyone like the Jew.” Hamas’ charter is replete with antisemitic references.

Goldhagen claims that racist antisemitism, a staple of Nazi Germany and its satellite states, is still propagated, and that the Internet has made “swirling streams” of antisemitism instantly available to everyone. He cites Jew Watch, with its 1.5 billion pages, as one of the most widely read antisemitic websites.

He accuses the political left, as well as the human rights community, of demonizing Israel and carving out a public space for the dissemination of antisemitism. But is legitimate and well-founded criticism of Israel the same as antisemitism?

Hardly.

In this connection, Goldhagen’s assertion that the United Nations has morphed into “an antisemitic institution” is plainly at odds with reality. True, the UN has often and unfairly singled out Israel. But does that mean that the UN itself is antisemitic?

No.

To Goldhagen, the most fundamental new fact about contemporary antisemitism is that it is global. “Never before could this be said about antisemitism,” he claims. How true is this? A century ago, for example, a Jew could easily encounter anti-Jewish animus not only in Europe, but in Canada, the United States, Russia, Germany, Hungary, Yemen, Brazil or Argentina.

In conclusion, he sounds a somber note: “Antisemitism, the real devil that Christianity spawned, has not died and shows no prospect of dying any time soon. In living, it has adapted and evolved and stalks the world ever more confidently as a global menace.”

One suspects that antisemitism will preoccupy Jews, Christians and Muslims for centuries to come.