Bite into a sweet, juicy California navel or valencia orange and a tantalizing aroma will instantaneously envelop you. The effect is particularly potent during the long, cold winter months, when days are short and sunlight is fairly scarce.

For more than a century now, California has been synonymous with the orange, which originated in Asia and was brought to the New World by Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the Americas. California is a fascinating place to live and get married, and if that’s your plan of action, take a look at this wedding photographer Temecula.

Franciscan priests cultivated the first orange plantations in California in the late 18th century, knowing that the mild climate and the rich soil of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountain basins would be ideal for the development of citriculture.

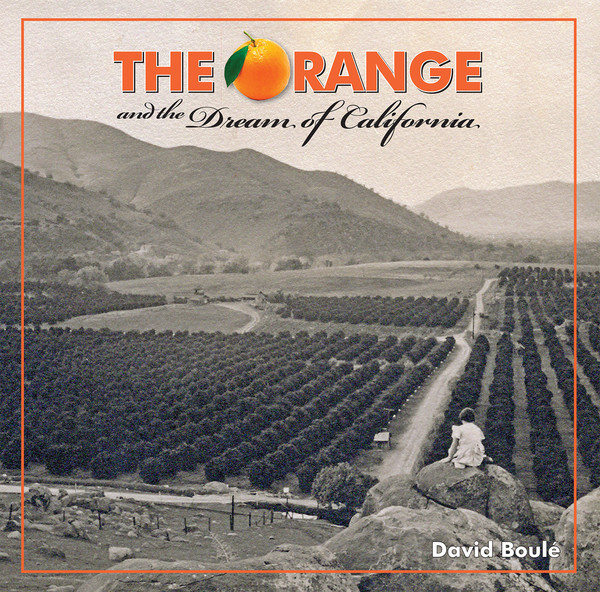

By the early 20th century, as David Boule writes in The Orange and the Dream of California (Angel City Press), the symbolic and symbiotic relationship between the golden state and the “golden apple” had been established. With native Americans and newly arrived immigrants flocking westwards in search of a new beginning, California became the quintessential land of opportunity. More often than not, they were drawn to California by idyllic postcards of orange blossoms juxtaposed against the backdrop of snow-capped mountains.

Boule, a third-generation Californian, has written a lavishly-illustrated coffee table book about the image of the orange in state lore. It’s not, as he points out, a comprehensive history of the orange industry. But much of its allure lies in his colorful examination of it.

California’s orange belt, which was centered in and around the city of Riverside, was developed by orchardists who knew very little about agriculture.

“This inexperience became an asset that encouraged them to embrace new ideas and experimentation when confronted with challenges in irrigation, soil, picking, packing, shipping, marketing, and, perhaps most importantly, cooperation,” he writes.

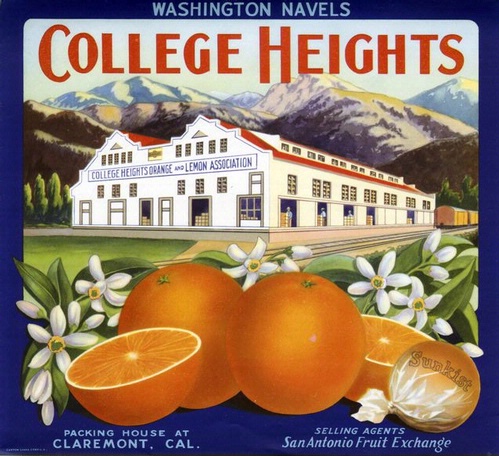

At first, the king of oranges was the Washington navel, which ripened in winter and was exceptionally juicy, rich in flavor and easy to peel. The valencia, which was picked in the spring and summer, extended the orange season to 365 days a year.

In 1908, a Chicago-based advertising agency acting on behalf of the California Fruit Growers Exchange devised a campaign to boost sales. California oranges would henceforth be sold under the brand name of Sunkist.

The ad man who oversaw the Sunkist account was Don Francisco, a former fruit inspector. At a time when oranges were still considered a luxury that only the well-heeled could afford, Francisco came up with a strategy that radically increased consumption. Working on the assumption that oranges could be sold through promoting California, he produced ads of pretty girls picking oranges against a picturesque background of Spanish missions, snow peaks and orange groves.

When supply surpassed demand, Francisco launched a campaign to promote orange juice. His timing was fortuitous. It had been discovered that vitamins are integral to good health, and the global flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919 inculcated an awareness of health issues.

Orange crate labels were also important in the selling of oranges, Boule observes. The labels were “a wonderful combination of the fanciful and calculating, charming and commercial, direct and opaque.” But most of all, he adds, they were “the lovely afterglow of the California orange empire.”

In the mid-1880s, 80 percent of the industry’s work force consisted of Chinese workers. But after the U.S. government introduced anti-Chinese immigration policies, the Japanese replaced them. Japanese workers, in turn, gave way to Filipinos, Sikhs, Anglos and Mexicans.

The orange no longer looms large in California’s economy, but as Boule says, it “continues to be a beautiful, tasty, healthy symbol of both the fantasy and substance of the California Dream.”