On a sparkling late summer day 30 years ago today, the tremors of a seismic shift in the Middle East were felt as two sworn enemies chose reconciliation, coexistence and peace over hostility, tension and war.

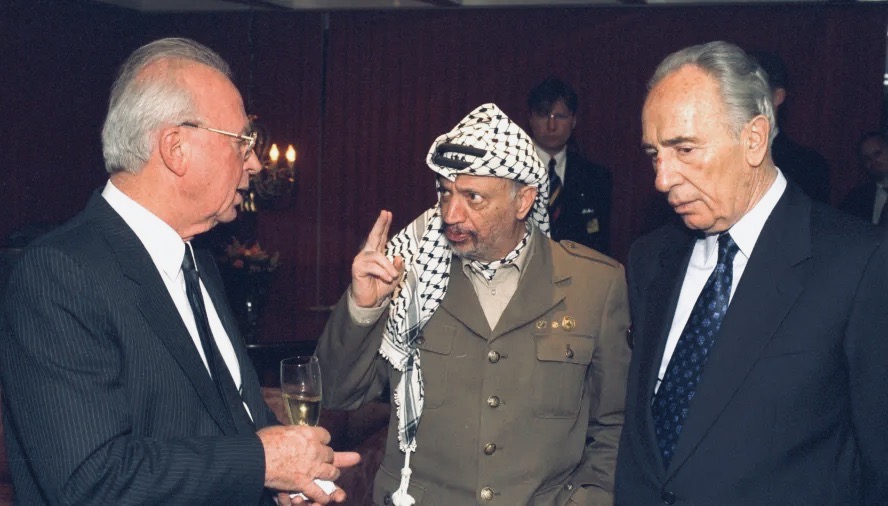

On September 13, 1993, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and his arch nemesis, Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, shook hands to seal the Declaration of Principles, which would be known as the Oslo Accord.

In terms of optics, the ceremony at which they appeared — which took place at the White House in Washington, D.C. and was presided over by U.S. President Bill Clinton — was a moment to remember in the tangled history of Israel’s relations with the Palestinians.

Oslo, in essence, was the culmination of violence and diplomacy.

The first Palestinian uprising, which raged from 1987 to 1990, pushed Israel closer to the glum realization that the Palestinians would never accept its military occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

The Madrid peace conference in 1990, which was attended by Israel, a Palestinian delegation, several Arab countries and the United States, jolted Israel into the belief that a diplomatic solution of its bitter and protracted dispute with the Palestinians might be possible.

The Declaration of Principles, hammered out in secret talks between Israeli and Palestinian negotiators in Norway, were path-breaking in their dimensions. Israel accepted the PLO as the representative of the Palestinians and the PLO renounced terrorism and recognized Israel’s right to exist.

The newly formed Palestinian Authority (PA), headquartered in the Gaza Strip, was charged with governing the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories over a five-year interim period.

Permanent-status talks on such core issues as final borders, Jewish settlements, Palestinian refugees, and the status of Jerusalem were scheduled to be completed in 1999, but the deadline was missed.

Oslo seemed like the harbinger of a new era, presaging the end of Israel’s struggle with the Palestinians. It was an all-consuming conflict that sucked major Arab countries, such as Egypt, Jordan and Syria, into a succession of skirmishes and wars with Israel.

While the majority of Israelis supported Oslo, a vocal and outspoken minority, who had no faith in Palestinian intentions and coveted the lands Israel had conquered in the 1967 Six Day War, denounced it as a sellout and a strategic blunder.

The rejectionist camp was led by Benjamin Netanyahu, the leader of the right-wing Likud Party, which opposed territorial compromise in principle. He and his allies, notably the settlers of the West Bank, mounted nation-wide protests and attacked Rabin as a traitor and likened him to a Nazi. One settler, Baruch Goldstein, vented his rage at Oslo by killing 29 Palestinians in a murderous rampage in Hebron in the winter of 1994.

Palestinians on the radical wing of the Palestinian national movement lambasted Oslo too, as did most Arab countries.

Despite the acrimony unleashed by Oslo, Israel and the PA signed yet another agreement on September 24, 1995 which divided the West Bank into three distinct parts.

Area A, which was fully controlled by the PA, comprised 18 percent of the West Bank and contained major Arab towns such as Ramallah, Nablus and Hebron. Area B, which was jointly administered by Israel and the PA, consisted of 22 percent of its land mass. Area C, which was fully in Israel’s hands and held its network of settlements and military posts, represented 60 percent of the West Bank.

Apart from these landmark agreements, Israel and the PA signed a series of accords regulating their bilateral relations.

Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement, excoriated Oslo. It launched a suicide bombing campaign in Israel in 1994 which targeted buses and public places.

Arafat usually deplored these assaults, but could not or would not stop them. Skeptics contended that he secretly encouraged the terrorist onslaught because he was never sincerely committed to the prospect of peace with Israel.

Oslo generally went against the grain of Palestinian public opinion because it had no provision for Palestinian statehood and did not explicitly ban the construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank or the Gaza Strip.

Rabin and his associate, Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, envisioned a process which would lead to full Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza, though they both understood that autonomy could well result in statehood.

Arafat sought a sovereign and independent state within those boundaries, if not more. Their divergence of views was a prescription for acrimony.

Although Rabin was not a champion of the settlement movement, he believed that settlements located near Israel’s border with the West Bank were necessary for its security. To the Palestinians, the settlements posed an insurmountable problem since they broke up the territorial contiguity of a future Palestinian state.

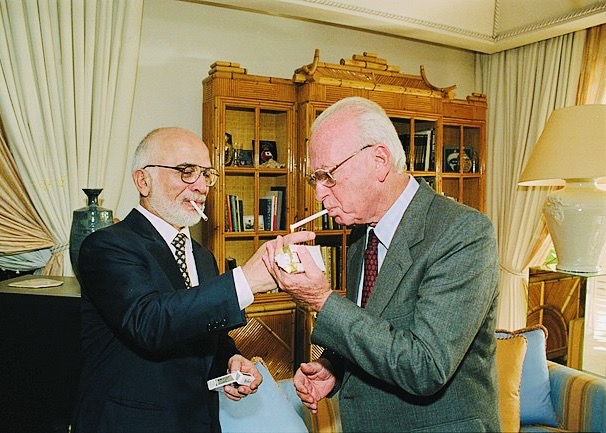

To the Israeli government, one of Oslo’s first tangible benefits was the peace treaty with Jordan, a vast desert kingdom which shared a long border with Israel and which had been part of Palestine until the early 1920s. Its ruler, King Hussein, who had long maintained secret contacts with Israel, had no territorial disputes with Israel. But since almost two-thirds of Jordan’s citizens were Palestinians, he had no alternative but to endorse Palestinian statehood.

After Oslo, King Hussein could afford to take the next logical step and follow in Egypt’s footsteps. Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty in October 1994.

Even as Israelis rejoiced over this seminal event, they were frightened and disillusioned by the spate of Palestinian suicide bombings, which definitely soured the spirit of Oslo. Palestinian terrorists, mainly from the ranks of Hamas, Islamic Jihad and the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, targeted civilians and soldiers alike.

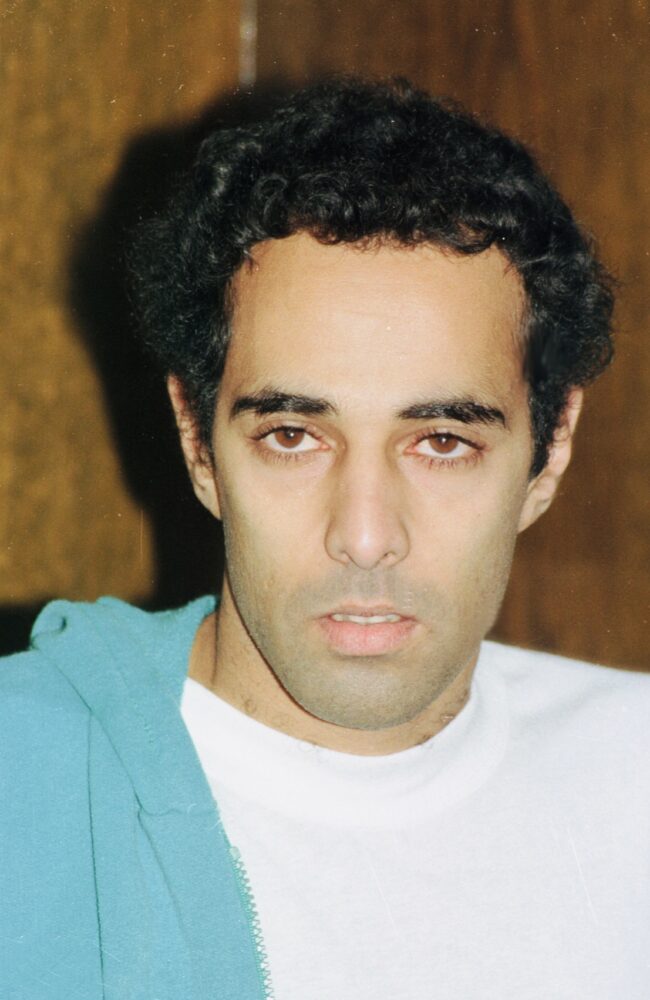

The attacks increased in tempo and ferocity after Israel’s assassination of Yahya Ayyash on January 5, 1996. Known as The Engineer, he was an extremely skilled Palestinian bomb maker whose devices had killed and maimed numerous Israelis.

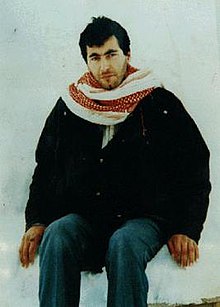

On November 4, 1995, a Bar-Ilan University student named Yigal Amir, a fierce opponent of Oslo, assassinated Rabin in the wake of an upbeat peace rally in Tel Aviv. His Labor Party successor, Shimon Peres, carried on with Oslo, but due to a succession of terrorist incidents which led to widespread disaffection among Israelis, he lost the 1996 election to Netanyahu, an arch foe of Oslo.

Netanyahu was less than eager to embrace the pro-peace policy of his predecessors. But succumbing to U.S. pressure, he deigned to meet Arafat and grudgingly agreed to continue with Oslo on condition of mutual Israeli and PA reciprocity.

Nevertheless, the level of mistrust between Israel and the Palestinian Authority sank to a new low in the summer of 1996, when 15 Israeli soldiers and dozens of Palestinians were killed in riots in eastern Jerusalem following Israel’s opening of an ancient tunnel complex beneath two holy sites, the Western Wall and the adjoining Temple Mount.

Bowing to yet more U.S. pressure, Netanyahu in 1997 reluctantly ceded 80 percent of Hebron to the PA, while reserving the rest for Jewish settlers, who had returned to their ancestors’ homes after the Six Day War.

To further appease his constituents, Netanyahu refused to withdraw from more territory in the West Bank, as called for in the Oslo agreement, and ordered the construction of Har Homa, a neighborhood in East Jerusalem.

Netanyahu went down to defeat in the 1999 election, losing to the Labor Party’s Ehud Barak, a former chief of staff of the armed forces. Seeking to end Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, he persuaded the United States and the PA to attend a make-or-break summit. It would be held at Camp David in the U.S. state of Maryland in July 2000.

Barak offered Arafat sweeping territorial concessions as well as statehood in disconnected parts of the West Bank in exchange for a peace settlement. Arafat walked away from Barak’s proposal, being dissatisfied with the Swiss cheese complexion of the map drawn by by Israel.

Two months after their unsuccessful meeting, the second Palestinian rebellion in 13 years erupted. Whether it was spontaneous or planned is still debatable, but it was certainly far bloodier than the first one, claiming the lives of more than 1,000 Israelis and some 3,000 Palestinians. It would fester until 2005, the year of Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza, a plan conceived and implemented by Ariel Sharon, who succeeded Barak as prime minister in 2001.

This intifada widened the chasm of mistrust between Israel and the PA, effectively emasculated Oslo, and turned Israeli public opinion on a definite rightward trajectory.

A Palestinian suicide bombing at the Park Hotel in Netanya in March 2002, the worst on Israeli soil since Israel’s establishment in 1948, claimed the lives of 30 Israelis. Within days of this atrocity, Israel launched Defensive Shield, its biggest military operation since the Six Day War. Israel reoccupied Palestinian towns in Area A, only to pull out some two months later. Israel also raided Palestinian refugee camps throughout the West Bank in an attempt to crush the infrastructure of terrorism.

Much to Israel’s frustration, the suicide attacks continued unabated, though less frequently.

During this turbulent period, Israel sidelined Arafat, confining him to PA headquarters in Ramallah. His successor, Mahmoud Abbas, denounced armed struggle as a strategy and supported a two-state solution. But subsequent diplomatic efforts to break the impasse failed.

Neither the 2007 “road map” proposal proffered by the United States, nor Abbas’ negotiations with Ehud Olmert, Sharon’s successor, could break the deadlock.

From 2013 to 2014, Israel and the PA engaged in on-again, off-again negotiations under the auspices of President Barack Obama’s administration, but they collapsed without a single tangible breakthrough.

President Donald Trump’s one-sided “peace plan of the century” floundered as well, though his initiative aimed at normalizing Israel’s ties with four Arab countries — the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan — largely succeeded.

Since 2014, Israel’s relations with the Palestinians have progressively worsened, though the PA has maintained security cooperation with Israel, much to the chagrin of the average Palestinian.

In most other respects, the Oslo process been mothballed, the object of demonization by substantial segments of the Israeli, Palestinian and Arab population.

The current Israeli government, the most right-wing in history, is surely glad and relieved that Oslo has been consigned to the dustbin. Since its formation last December with Netanyahu at its helm, the Israeli government has expanded Israel’s footprint in the West Bank, utterly dismissed the possibility of a two-state solution, and ruled out peace talks with the PA.

Oslo began with high hopes and expectations, but has since fizzled and is now little more than a faint memory.