Hamas spokesmen have been consistently clear why it carried out the devastating terrorist attack in southern Israel on October 7.

First, Hamas sought to revive the Palestinian issue, which had fallen by the wayside following the 2020 Abraham Accords. Under the terms of this historic agreement, Israel formed ties with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan within a matter of months.

Second, Hamas wanted to torpedo Israel’s efforts to capitalize on the Abraham Accords by normalizing relations with Saudi Arabia. Israel had hoped to achieve this objective without seriously addressing the lingering Palestinian question.

Third, Hamas hoped to obtain the release of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails.

No one can deny that Hamas has achieved these objectives, more than a month after its bands of terrorists murdered 1,200 Israelis and foreigners, kidnapped some 240 hostages, and triggered the fifth Gaza war in fifteen years.

Since then, the Palestinian issue has resurfaced after a fairly lengthy period of dormancy. It is now getting a new hearing internationally. Saudi Arabia, the seat of Islam, has shelved plans to forge what could have been a truly historic rapprochement with Israel. And on November 24, Israel released the first batch of Palestinian prisoners in exchange for some Israeli hostages.

For Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who last December formed the most right-wing government in Israeli history, these are huge setbacks.

It is almost forgotten today that Netanyahu once embraced a two-state solution under one major condition. Succumbing to intense U.S. pressure, he accepted that formula in 2009, when he established his second government in thirteen years.

A Zionist Revisionist who believes that the West Bank is the homeland of the Jewish people, he had previously rejected the notion of Palestinian statehood, calling it a dire threat to Israel’s security. In temporarily shifting his hardline position, he insisted that a future Palestinian state would have to be demilitarized. But he never spelled out the exact boundaries of such a state.

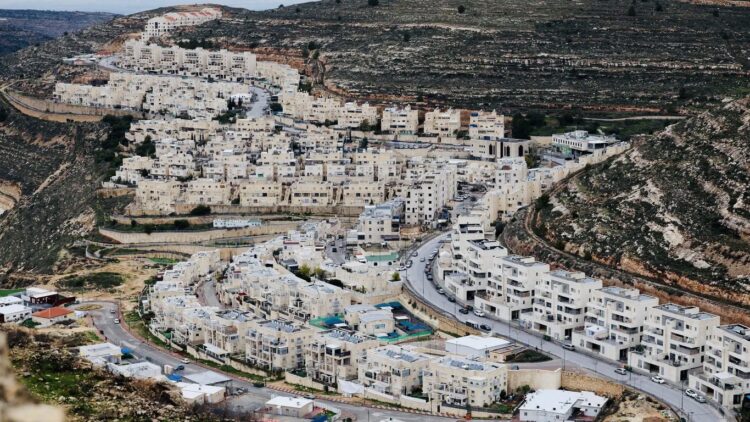

In reality, Netanyahu paid nothing more than lip service to a two-state solution as he expanded Jewish settlements in the West Bank and cut off contact with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas after the failure of U.S.-brokered peace talks between 2013 and 2014.

Prior to this, Israel and the Palestinian Authority tried but failed to reach a final status peace agreement.

During Donald Trump’s presidency, Netanyahu disclosed his real agenda when he openly acknowledged that the best deal he could offer the Palestinians was a limited form of autonomy in the West Bank, an outcome they could not accept under any circumstances.

With the signing of the Abraham Accords, which mentioned the Palestinians only in passing, Netanyahu grew yet more confident that he could kick the Palestinian issue even further down the road.

U.S. President Joe Biden was indirectly complicit in shaping this reality. Although he talked about the need for a two-state solution, he did not really press Israel to act on it, Instead, like Trump, he focused on bringing Saudi Arabia, a U.S. ally, into the Abraham Accords.

Senior Saudi officials claimed that an agreement with Israel would only be possible if there was progress toward there attainment of Palestinian statehood. But in a telling comment on the eve of Hamas’ attack last month, the Saudi crown prince and heir to the throne, Mohammed bin Salman, admitted that an “easing of conditions” for Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied West Bank would be sufficient for him to officially recognize Israel and join the Abraham Accords.

Watching these developments from Gaza, Hamas, an opponent of a two-state solution, feared that the Palestinians were being abandoned to their fate, and that the expansion of the Abraham Accords, with Saudi Arabia as its latest member, would greatly strengthen Israel and sideline the Palestinian cause.

Since the October 7 massacre and the resultant war in the Gaza Strip, the Palestinian issue has been reinvigorated. In recent weeks, Biden, French President Emmanuel Macron and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, among others, have added their voices to it.

Biden, in particular, has stressed the need for Palestinian independence and sovereignty within the framework of statehood. “There has to be a vision of what comes next,” he said last month. “In our view, it has to be a two-state solution.” Last week, Biden said, “I can tell you, I don’t think it (the Israel-Hamas war) ultimately ends until there’s a two-state solution.”

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has raised this issue as well. After one of his last visits to Israel, he said, “Anything that would move us away from that vision is, in our judgment, detrimental to Israel’s longterm security and longterm identity as a Jewish and democratic state.”

The Palestine Liberation Organization, an advocate of a two-state solution since the 1993 Oslo peace process, entered the debate two weeks ago. This occurred after Blinken suggested that the Palestinian Authority must play a central role in governing Gaza once Israel demolishes Hamas and unseats it as the governing body.

Hussein al-Sheikh, the secretary-general of the Palestine Liberation Organization, said the Palestinian Authority would favorably consider this option if the United States commits to a full-fledged two-state solution in the West Bank and Gaza and a resolution of core issues.

It is highly doubtful whether the current Israeli government would even consider the notion of Palestinian statehood, particularly in the wake of the Hamas massacre, which summoned up images of 19th century Russian pogroms and the Holocaust.

Israeli public opinion, which has been on a rightward course since the Six Day War, has shifted even further to the right since October. And the level of mistrust between Jewish Israelis and Palestinians has rarely, if ever, been as low as it is today.

Many years may elapse before Israel can restore its deterrence following the ghastly intelligence and military failures of October 7. Only then might the majority of Israelis feel more comfortable in discussing the possibility of a two-state solution.

If Israelis are forced to address Palestinian statehood sooner rather than later, Israel would require a new prime minister at the helm of a much more reasonable government. The same logic applies to the Palestinians. The Palestinian Authority, which has been widely accused of corruption and inefficiency, will have to be revamped, with a far younger, more dynamic leader replacing Abbas.

In any event, public support for a two-state solution among Israelis and Palestinians has reached a historic nadir in recent years.

According to a survey published by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Research earlier this year, 33 percent of Palestinians and 34 percent of Israeli Jews support a two-state solution, a significant drop since 2020. Two-thirds of Palestinians and 53 percent of Israeli Jews are antagonistic toward it.

Ultimately, Israel can only resolve its protracted conflict with the Palestinians by political rather than by military means. But at the moment, with emotions running red hot in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank, the prospect of Palestinian statehood is illusory.