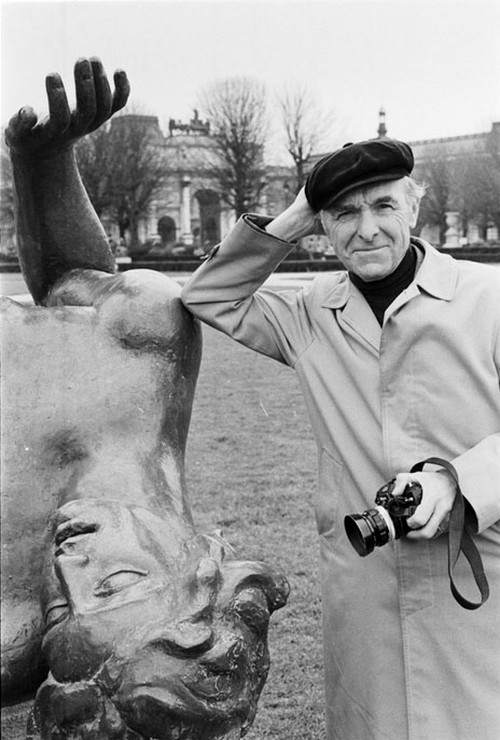

Robert Doisneau (1912-1994) was a remarkable photographer, often mentioned in the same breadth as the illustrious Henri Cartier Bresson. A lithographer and engraver by trade, he slipped into photojournalism gradually. By the 1950s, he was well established, known in particular for his photographs of Paris.

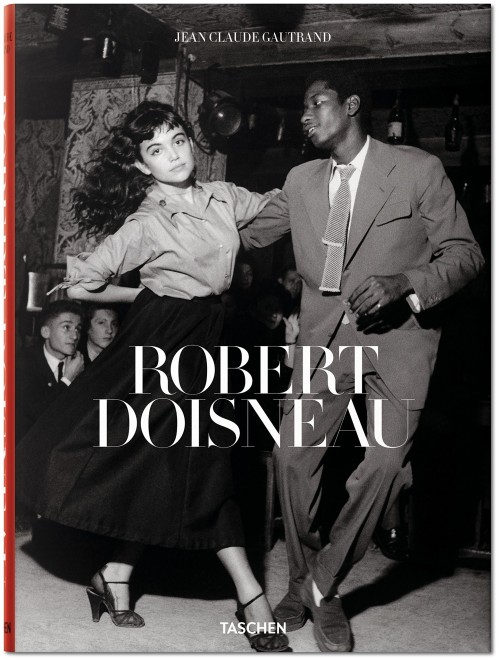

Jean Claude Gautrand’s lavishly-illustrated coffee-table book, Robert Doisneau, published by Taschen in English, French and German, is an ode to the renowned French photographer. It contains hundreds of his smartly-crafted photographs, nearly all of which are in black and white.

Striving to capture images that expressed the simple joys of urban life, Doisneau frequented the old streets of Paris and its suburbs, focusing on the glances and smiles of people he randomly encountered. He was interested in spontaneity, not in artifice.

His earliest photographs, from the pre-war era, are guileless and candid — three girls skipping rope in a park, an artist committing a painting to a canvas in the courtyard of the Louvre, a group of Parisians sitting idly on the banks of a river.

For a while, Doisneau was employed by Renault, the car manufacturer. The sharp and evocative photographs he produced of a busy assembly line, a worker taking a cigarette break and three young Parisians enjoying on a road trip in the countryside in a Renault transcend the bounds of the ordinary.

Doisneau’s photographs of Paris under Nazi occupation are oddly benign, except for an edgy image of Parisians looking curiously skyward during an air raid warning. His compositions of Paris’ liberation, in August 1944, are stronger. Parisians build barricades in the Latin Quarter. A collaborator, his hands behind his head, is marched away by two policemen. Charles de Gaulle, resplendent in an army uniform, walks along the Champs-Elysees, an entourage following in his wake.

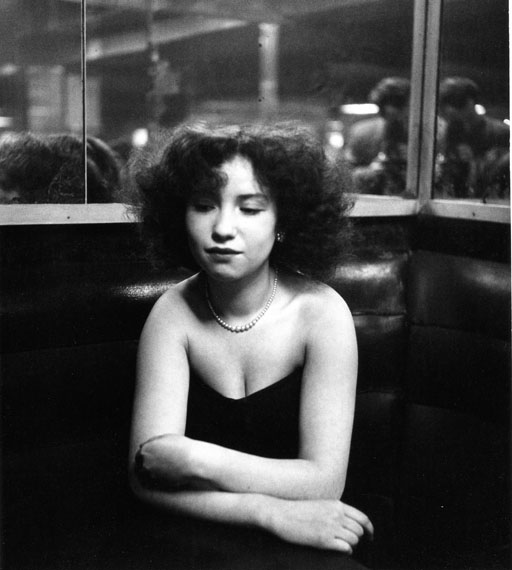

The postwar photographs exude a sense of calm and serenity. A young woman in a black dress, her cleavage exposed, sits quietly in a bar. What is she thinking? An attendant in a nursery brimming with babies weighs a toddler. A woman in a skirt, gazing expressively at the camera, dances with an African man clad in a suit and tie. A prostitute waits for a customer.

Doisneau’s fashion photographs, including one of Yves St. Laurent standing behind a scantily-dressed model, are glamorous yet charged with tension. His celebrity portraits of Saul Steinberg, Maurice Utrillo, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, some of which are in color, are naturalistic.

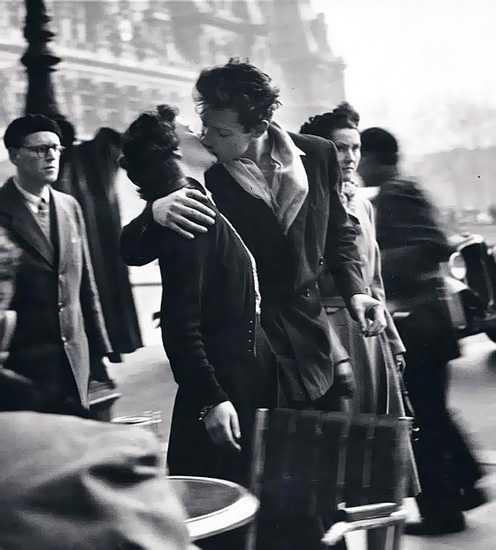

He stumbles upon Parisians in a variety of pursuits. An old man brandishes a fishing rod. A boy riding a bicycle tows a girl on skates. Two nude female dancers accept candy from a formally-dressed man. In one of his most famous photographs, lovers kiss amid the clamor of pedestrians and traffic.

His portraitures radiate strength. Two women face the camera provocatively, a man sitting impassively on the side. Jack Lang, the minister of culture, stands in a room pensively. The actress Isabelle Huppert, her legs crossed, sits alone in a bar.

Doisneau’s photographs of unguarded moments and of times long gone are stripped down to their barest essentials, revealing unvarnished truths.