Ahmad Fadil al-Khalayeh was a petty criminal, a pimp and a drug dealer, during his misspent youth in Jordan. By the time he changed his name to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, he had become an Islamic fundamentalist and a feared terrorist.

Zarqawi was the first leader of Islamic State — the jihadist organization that has since seized vast swaths of territory in Iraq and Syria, killed thousands of Iraqi civilians in suicide bombings, beheaded Western captives in Syria and brought death and destruction to Ankara, Beirut and Paris.

His soft-spoken and cultured Iraqi successor, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, whose real name was Ibrahim Awad al-Badri, has taken Zarqawi’s jihad to a higher, more dangerous level.

Through these two individuals, Joby Warrick — a reporter on the staff of The Washington Post — charts the alarming rise of Islamic State. He does so in Black Flags (Doubleday), an exceptionally fine book based on original reporting and first-hand interviews.

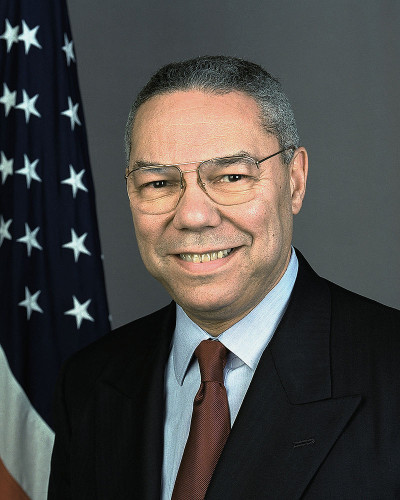

As Warrick observes, the U.S. secretary of state, Colin Powell, had the dubious distinction of introducing al-Zarqawi to the world. On February 5, 2003, in a speech to the United Nations Security Council, Powell laid out the American case for going to war against Iraq. In an erroneous attempt to link the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein, with Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, Powell claimed: “Iraq today harbors a deadly terrorist network headed by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, an associate and collaborator of … bin Laden and his Al Qaeda lieutenants.”

When Powell uttered these accusatory words, Zarqawi was a virtually unknown jihadist. But in the aftermath of Powell’s speech, Zarqawi came to be regarded as “an international celebrity and the toast of the Islamist movement,” says Warrick.

Powell’s claim that Iraq harbored Zarqawi was patently false. While Zarqawi happened to be operating in Iraq when Powell singled him out as a singular threat, he was neither Saddam’s friend nor ally. Zarqawi sneaked into northeast Iraq by way of Iran after fighting in Afghanistan. He then joined Ansar al-Islam, an extremist Kurdish group whose doctrinaire ideas he found appealing.

By that juncture, this remote region in Iraq was no longer in Saddam’s hands, having morphed into a semi-autonomous Kurdish enclave during the 1991 Gulf War. Since then, it has been protected by a U.S. no-fly zone.

Sizing up the geopolitical realities in the region, Zarqawi said, “Iraq will be the forthcoming battle against the Americans.” He made that prescient prediction about a year before the United States and its allies invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime. Subsequently, Zarqawi was one of the prime leaders of the insurgency, which pushed Iraq to the brink of an all-out civil war and claimed the lives of countless Iraqi and American soldiers and civilians.

Who could have known that this rough-hewn hoodlum from the bleak Jordanian city of Zarqa would transform himself into one of the most notorious figures in the annals of the Middle East?

Born into a working-class family, Zarqawi was a high school dropout with a reputation as a heavy drinker and street brawler. Deeply into pimping and drug dealing, he seemed like a hopeless case. His beloved mother signed him up for religious classes at a mosque, hoping he would find suitable role models among the imams and pious teenagers. “To everyone’s surprise, Zarqawi plunged into Islam with all the passion he had once reserved for his criminal activities,” Warrick writes.

Zarqawi arrived in Afghanistan in 1989, just weeks after the Soviet army had withdrawn but still in time to join an Islamist assault on the pro-Moscow Afghan government. He left the country four years later, having received military training and having been steeped in the doctrine of radical Islam.

Returning to Jordan, he worked as clerk in a video store and joined a local Islamist organization. Fired up by the murderous rampage of Baruch Goldstein — a Jewish settler who killed 29 Palestinians in the West Bank town of Hebron in 1994– Zarqawi and his associates planned an attack on an Israeli settlement near the Jordanian border. Jordan’s secret service learned of the plot, which also entailed attacks on Christian shrines and a hotel in Amman, and arrested him. He and a fellow plotter were given a 15-year prison sentence. They were released in 1999 as part of a general amnesty following the death of King Hussein of Jordan.

After establishing a jihadist training camp in Iraq under the auspices of Al Qaeda, Zarqawi dispatched envoys to Middle Eastern and European capitals in search of volunteers, money and allies. Later, in an attempt to create chaos in Iraq, he attacked American troops in hit-and-run raids, launched a succession of suicide bombers to kill as many Iraqis and Americans as possible and ignited conflict between Sunnis and Shiites.

In one of his most audacious operations, he ordered the bombing of the United Nations compound in Baghdad, killing the UN representative, the Brazilian diplomat Sergio Vieira de Mello. Then, in a brutal demonstration of his disdain for Shiites, he bombed the Askari mosque in Samarra, the most revered Shiite house of worship in the country, setting off a chain reaction of sectarian warfare.

Embittered former Iraqi army officers offered their services to Zarqawi, having been rendered jobless by the U.S. decision to dissolve Iraq’s armed forces.

By Warrick’s estimate, Zarqawi was an able field commander, “capable of transforming waves of untrained recruits into soldiers and suicide bombers who struck with purpose and discipline.”

Zarqawi set his sights on Jordanian interests, too, bombing Jordan’s embassy in Baghdad and attempting to carry out a chemical attack in Amman. In 2005, Zarqawi’s suicide bombers set off explosives in three of Amman’s finest hotels, killing 60 Jordanians.

Eventually, the United States put a price on his head, increasing the reward for information leading to his arrest from $10 million to $25 million. In the meantime, U.S. commandos, led by General Stanley McChrystal, stepped up their campaign against his command structure, eliminating scores of mid-level operatives.

Al Qaeda coopted Zarqawi, designating him as the emir of its branch in Iraq. But as increasing number of Muslims were killed by his fighters, Al Qaeda reprimanded him for his gratuitous use of violence.

Zarqawi, having been injured in Afghanistan by a U.S. air strike, was gravely wounded when an F-16 bombed his house in June 2006. He died of his wounds. He was succeeded by Islamic scholar Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the son of a conservative Muslim imam from Samarra. Baghdadi, who had fought against the Americans after 2003, was captured in Fallujah and briefly imprisoned in Camp Bucca, a breeding ground for jihadists.

After Zarqawi’s demise, the United States mercilessly pummelled the Al Qaeda franchise in Iraq, but Baghdadi pressed on, pulling away from Al Qaeda’s orbit and forming the Islamic State in Iraq. In 2013, it got a new name, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. Last year, Baghdadi finally settled on its current shortened name, Islamic State.

Baghdadi’s overarching objective, the establishment of a borderless caliphate in the Middle East, is opposed by Al Qaeda on strategic grounds. Al Qaeda holds that the first priority is to unseat the region’s secular Arab regimes. Al Qaeda also believes that shocking displays of violence, like beheadings, offend mainstream Muslims.

Islamic State, with at least 30,000 fighters in its ranks, has fared relatively well since seizing the eastern Syrian city of Raqqa in 2013, the first one it ever conquered. In 2014, Islamic State captured Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. According to Warrick, Islamic State’s land holdings today in Iraq and Syria are greater than the land areas of Israel and Lebanon combined.

With chapters in more than a dozen nations, including Saudi Arabia, Libya, Yemen, Algeria and Nigeria, Islamic State has developed into a formidable force. Its coordinated attacks in Paris on November 13, which claimed the lives of 130 people, prove it’s a clear and present danger.