When Polish-Jewish relations are discussed at any length, one of the topics that usually evokes heated debate revolves around the relationship between the Home Army (AK) and Jews. The largest resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Europe, the AK had an estimated membership of 350,000 and represented a cross-section of Polish society.

In general accounts of modern Poland published abroad, especially in Polish emigre circles, the AK has been seen as an heroic underground movement that fought the Nazis tooth-and-nail. But in the eyes of the former Communist regime in Poland, the AK was regarded much less favorably. Many Jewish historians, meanwhile, claimed that the AK was hostile to Jews.

Joshua D. Zimmerman, the author of The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939-1945 (Cambridge University Press), adopts a middle-of-the-road approach to this complex issue in his superb book. As he writes, “I argue that because the Home Army was an umbrella organization of disparate Polish organizations … from all regions ranging from socialists to nationalists, its attitude and behavior toward the Jews varied widely.”

Some AK factions assisted Jews. Others were indifferent. Still others were hostile.

As he sensibly points out in the paperback edition, the AK’s response to the Nazi persecution of Poland’s 3.3 million Jews was partly shaped by the positions its members had adopted before World War II. While socialists, communists and leftist democrats condemned antisemitism, a very serious problem in interwar Poland, center-right politicians from the Party of Labor and right-wing nationalists from the National Party supported the curtailment of Jewish civil rights, economic boycotts aimed at Jews and mass Jewish emigration.

Joseph Pilsudski, the revered and longtime Polish leader, respected Poland’s national minorities, including Jews. But after his death in 1935, the country was collectively ruled by his oldest associates in the Camp of National Unity. They included President Ignacy Moscicki, Prime Minister Felicjan Slawoj-Skladkowski, Foreign Minister Jozef Beck and armed forces chief of staff Edward Rydz-Smigly. They moved Poland in a more authoritarian direction, and while they rejected physical violence against the Jewish minority, they eventually endorsed the National Party’s radical position on Jews.

Poland, quickly conquered by Germany and the Soviet Union in September of 1939, suffered the loss of 71,500 soldiers, of whom 7,000 were Jews. By comparison, German casualties were 16,000.

With Poland’s defeat, a Polish-government-in-exile emerged led by Prime Minister Wladyslaw Sikorski. While he had questioned the patriotism of some left-wing Jews and had been in favor of voluntary mass Jewish emigration, he accentuated the positive in a speech delivered in Paris in October of 1939. Speaking in its largest synagogue, he affirmed his government’s commitment to full minority rights.

The AK, known in Polish as the Armia Krajowa, was formed toward the end of September 1939 by General Michal Tokarzewski and the mayor of Warsaw, Stefan Starzynski. Working closely with the government-in-exile in Paris and then London, the AK would provide the first reports on the Holocaust and the German maltreatment of Polish Jews.

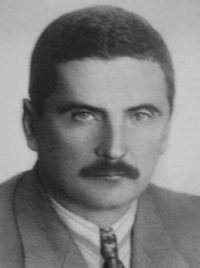

The second commander of the AK, Stefan Rowecki, assumed his duties in 1940 and held the post until his arrest and execution in 1943. A high-ranking army officer, he was apolitical, left-leaning and, in Zimmerman’s words, “evidently neutral” toward the so-called Jewish question, which consumed Poland even as Germany brutalized it.

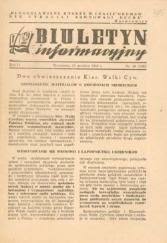

The first coverage of Jewish matters in AK media appeared in Biuletyn Informacyjny in January 1940 when it forbade Polish collaboration with the Germans. Around this time, Jan Karski, an AK courier, was asked by Stanislaw Kot, the government-in-exile’s minister of information, to write a report on Polish-Jewish relations in the homeland. Karski, a searingly honest observer, reported that Poles were not well-disposed toward Jews, and that Poles in the eastern sector of the country believed that Jews had collaborated with the Soviet Union at Poland’s expense.

Toward the close of that year, Prince Janusz Radziwill, a conservative prewar politician and member of the Camp of National Unity, wrote that while the Polish population categorically disapproved of German mistreatment of Jews, antisemitism “still exists among all segments of society.”

An AK intelligence report confirmed his appraisal: “That which the (German) occupiers have already managed to accomplish in the struggle against the Jews exceeds the wildest dreams of even the most rabid antisemites … Many Poles are expressing satisfaction among themselves that the Jews are being removed … from Polish residential districts, official positions, the free professions, industry and commerce … A certain percentage of the Poles behave kindly toward the Jews.”

A report from the AK branch in Lwow reached a similar conclusion: “The vast majority of Polish society assumes a hostile, or, at the very least, negative attitude … to the Jews … The majority, neverthelesss, condemn the brutal German methods.”

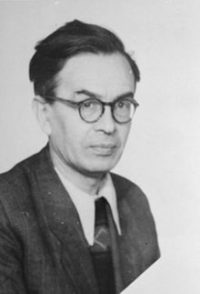

Throughout the initial phase of Germany’s occupation, Zimmerman notes, the AK press carried reports about appalling conditions in Nazi ghettos — the congestion, the hunger and starvation, the epidemics, the methodical plundering. Much of this information was gathered by the AK’s Jewish Affairs Bureau, which was formed in 1942 and headed by Henryk Wolinski, a democrat friendly toward Jews.

In the wake of the Red Army’s retreat from eastern Poland in 1941, pogroms broke out in 66 towns and villages, precipitated by the widespread belief that Jews had committed treason by having welcomed the Soviets and cooperated with them. An AK report said, “The hostility of the Poles toward the Jews is so enormous that local Poles cannot imagine a return to normal relations with Jews in the future.” Rowecki wrote, “… the overwhelming majority of (Poles) is of an antisemitic orientation …”

To Jews, however, the Red Army was viewed as a savior, sparing them from Nazi atrocities.

Claiming that Jews under the Soviets had behaved hideously from “the Polish perspective, Kot wrote, “Polish society is terrified of excessive Jewish influence. It is afraid that the need to import foreign capital into a decimated Poland would give the international financial Israelite magnates excessive power …”

As these reports were issued, Sikorski, in a speech in early 1942, said, “Poland undoubtedly respects freedom and the civil rights of all citizens faithful to the Republic, regardless of nationality, religion or race …” But in the same year, he instructed the AK to bar national minorities from its ranks. Rowecki opposed this policy but field commanders ignored him.

AK media covered and condemned the massive Nazi deportations of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto in the summer of 1942 and reported they had been taken to extermination camps in Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor. Yet as these events occurred, an AK member from Lwow reported, “The Polish public has disgust for the oppressors (but) a tepid attitude toward the Jews. They strongly sympathize with individuals among the Jews and will risk their lives to help them. But in relation to the Jewish community as a whole, (these same Poles) feel subconscious pleasure that there will be no more Jews in Polish life.”

As Jewish fighters in the Warsaw ghetto prepared for a life-and-death battle with the Germans, they appealed to the AK for arms. A few months before the 1943 ghetto uprising erupted, the AK sent a small quantity of weapons — 50 pistols and 50 hand grenades — but AK commanders believed they would never be used or would be utilized ineffectively. The leadership of the Jewish Combat Organization considered the shipment important but inadequate.

The AK’s limited aid was a reflection of Sikorski’s assessment that a premature start of a general rebellion would cost the general population dearly and deal a heavy blow to the resistance movement, says Zimmerman. Nonetheless, the AK devised a plan to blow up a ghetto wall to allow for mass escapes. The mission failed after collaborationist Polish Blue Police spotted AK units and alerted a nearby German SS unit. During an ensuing exchange of fire, two AK fighters, Jozef Wilk and Eugeniusz Morawski, both aged 18, were killed. During the uprising itself, the AK conducted seven solidarity actions in support of the ghetto fighters, sustaining 30 casualties.

With the uprising crushed after about a month, Biuletyn Informacyjny reminded its readers that “our duty is to provide assistance in sheltering and protecting (Jews) from the Germans.” The Committee to Aid Jews, or Zegota, did just that with the active cooperation of the AK.

Under Rowecki’s successor, Tadeusz Komorowski, relations between the AK and Jews deteriorated. Komorowski, a prewar supporter of the National Party, was in favor of protecting unarmed Jewish civilians in hiding. But claiming that Jews were perceived by Poles as a “foreign element,” he was willing to send ghetto fighters only a minimal number of weapons. As the tendency to conflate Jews with the Soviet Union and communism took hold, he ordered AK units in eastern Poland to hunt down and eradicate “Jewish-communist bands.”

Wladyslaw Liniarski, the commander of the AK in Bialystok, carried out this mission with zeal and ferocity. Several members of an AK detachment in Kielce also murdered Jews.

Liniarski was negatively disposed toward Jews. As he wrote in a memo submitted to the Polish-government-in exile, “No matter how monstrous are German crimes against the Jews, for Polish society the removal of Jews from this area … has brought about the end of the Jewish problem … People remember Jewish influences on the destruction of Polish culture during Bolshevik rule … The absence of jews (sic) in trade in the Bialystok district is a true blessing…”

Despite the persistence of antisemitism within the AK, Zimmerman says, a few of its members in the Lwow and Vilna regions saved Jews and recruited them as underground fighters. Bronislaw Krzyzanowski and his wife, Helena, were two such Poles. A Jewish survivor who was helped by the AK had this to say, “The Home Army was a huge organization over a large area and each section was unique. One absolutely cannot make a definitive statement about the Home Army’s attitude to the Jews.”

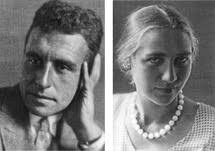

Four hundred to 500 Jews fought with the Home Army during the 1944 Warsaw uprising. Yitzhak Zuckerman, who had taken part in the Warsaw ghetto rebellion, was one of them, as was Stanislaw Aronson, whose unit captured the site from which Jews had been deported to Nazi death camps. The AK treated Zuckerman and his fellow Jews respectfully. “I didn’t sense antisemitism even once, neither from the civilian population nor from the AK,” said Zuckerman.

But, as Zimmerman notes, upwards of 30 Jews were murdered by AK units during the uprising, which resulted in the virtual destruction of Warsaw.

In closing, he says that the attitude of the AK toward Jews varied from region to region, and on the local level it depended on the views of individual leaders. At the end of the day, as the Polish political theorist Sofia Stemplowska has observed, the AK, at best, compiled a “mixed” record vis-a-vis its attitude and treatment of Jews.