With bold and stunning strokes, Syrian rebels have uprooted the autocratic Assad dynasty, ended the long-running civil war in Syria, and upended the political order in the Middle East.

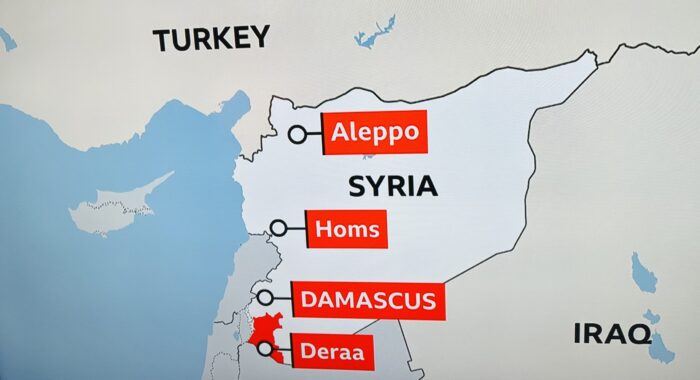

Yesterday, rebel forces stormed Damascus, the capital, after capturing Aleppo, Hama and Homs in a lightning offensive launched on November 27 from northwestern Idlib province.

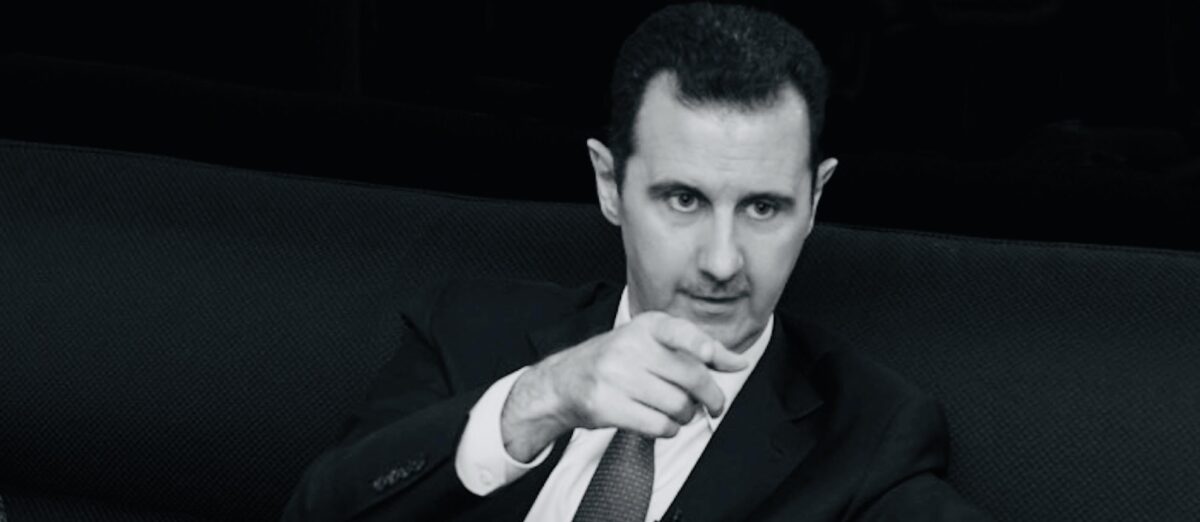

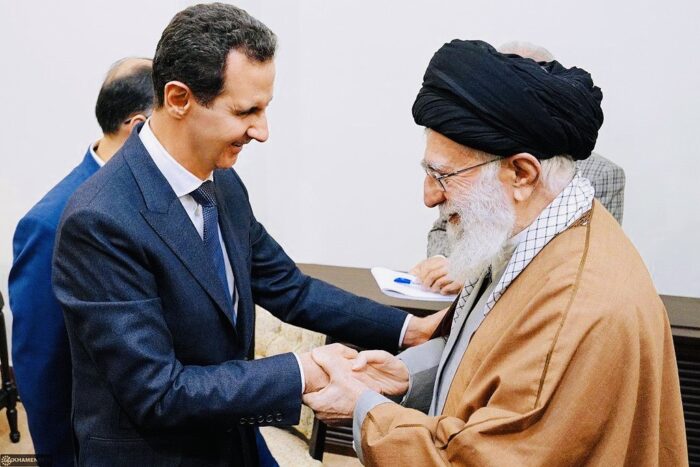

By then, President Bashar al-Assad, who began as a reformer but who ruthlessly ruled Syria with an iron fist for the past 24 years, had fled to Moscow. His chief backers, Russia, Iran and Hezbollah, proved to be impotent and were unable to stave off his ignominious defeat.

Surprisingly, the Syrian army put up little or no resistance. Syrian Prime Minister Mohammed al-Jalili offered to cooperate with the rebels, headed by Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, the leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a jihadist group once linked to Al Qaeda and Islamic State.

It was truly a geopolitical earthquake, the most consequential seismic shift in the region since Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution, which ousted the pro-U.S. Pahlavi monarchy and replaced it with a fervently anti-Western Islamic fundamentalist regime that morphed into the U.S.’ and Israel’s deadliest enemy.

Assad’s precipitous fall followed 13 years of civil war that devastated Syria, displaced millions of Syrians and resulted in the deaths of upwards of 500,000 of its citizens.

It brought to mind the collapse of three previous Arab regimes.

Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s tyrannical president, was overthrown by the United States during its invasion of Iraq in 2003. In 2006, he was hanged.

Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who succeeded Anwar Sadat in 1981, was forced to step down during the Arab Spring in 2011. Mubarak was succeeded by Mohammed Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood functionary who was toppled by Egypt’s current president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, in 2013.

Muammar Gaddafi, the longtime dictator of Libya, was murdered by Libyan rebels in 2011 during a protracted rebellion triggered by the Arab Spring.

And now Assad, who inherited the presidency in 2000 from his father, Hafez al-Assad, is gone too.

It is impossible to predict with any certainty who will replace Assad, a member of the minority Shi’a Alawite sect. But the odds favor Jolani, whose real name is Ahmed Hussein al-Shura, a Syrian who was born in Saudi Arabia and whose family returned to the homeland in the late 1980s.

Jolani went to Iraq in 2003, joined Al Qaeda, fought against the American occupation as an Islamic State operative, and spent several years in a U.S. prison in Iraq. Distancing himself from these jihadist organizations in 2016, he played a central role in the establishment of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which has been designated as a terrorist group by the United States.

Until recently, he was based in Idlib, a breakaway province in the northwest that Assad had been unable to recapture.

For the past eight years, during which the Syrian civil war was in remission, Jolani downplayed the radical Islamic roots of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and attempted to portray it as a nationalist force tolerant of political diversity and ethnic and religious minorities. Jolani’s pivot may be nothing more than a clever public relations ploy designed to curry favor with Syrians and the international community.

Whatever the case may be, the civil war has finally drawn to a close and Syria now has entered an uneasy transitional period of uncertainty, instability and power struggles. There is no guarantee that Hayat Tahrir al-Sham will prevail and form a government. The Syrian National Army, a rebel group backed by Turkey, may well want a slice of the pie.

But what seems certain is that the historic events in Syria have dealt severe blows to Russia, Iran and Hezbollah.

Russia, preoccupied by the two-year-old war in Ukraine, has lost a crucial partner in Assad — its chief Arab ally in the Arab world — and much of its influence in Syria. Russia has two Syrian military bases, and one can only wonder whether Syria’s new leaders will tolerate them. It would not be surprising if the United States replaces Russia as the dominant superpower in Syria.

Iran, its air defence batteries having been destroyed by Israel in retaliatory air strikes on October 26, has been further weakened by the demise of the Assad family Ba’athist regime, which took control of Syria 54 years ago.

With the Syrian rebels regarding the Iranian regime as an intractable foe, it is probably safe to say that Syria, Iran’s most important regional base, has exited its Axis of Resistance.

This anti-Israel alliance was established by the late Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, an arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps. Its objective is to surround Israel with a “ring of fire” and destroy the Jewish state. Apart from Syria, its members include Hamas, the Houthis of Yemen and Hezbollah.

With Assad out of the picture and with Israel having decimated Hezbollah’s leadership and smashed its military capabilities in southern Lebanon, Hezbollah is weaker than ever before.

Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz correctly hailed the most recent developments as “a severe blow to the Iranian axis of evil.”

“The octopus tentacles are being cut off one by one,” he added.

For Israel, Syria’s neighbor, the removal of Assad poses potential dangers and remarkable opportunities.

Syria’s new leadership may well perpetuate its traditional hostility toward Israel. Syria has fought four wars and numerous skirmishes with Israel since 1948. A peace agreement eluded Syria and Israel in the 1990s and 2000, but one may be possible if Syria readjusts its attitude and Israel signals a willingness to withdraw from most or all of the Golan Heights, the volcanic plateau overlooking the Sea of Galilee that was conquered by the Israeli army in the final hours of the 1967 Six Day War.

Even if this scenario fails to materialize, Israel would likely be pleased if Iran is shut out of Syria and Syrian territory no longer serves as an arms conduit to Hezbollah.

Two days before Syrian rebels entered Damascus, the Israeli Air Force bombed a border crossing between Syria and northern Lebanon which has been used to transfer weapons to Hezbollah.

On December 8, in the wake of Assad’s downfall, the Israeli Air Force bombed ammunition and weapons depots throughout Syria, fearing this weaponry could fall into the hands of Hezbollah and other enemies that could threaten Israel. In addition, Israeli jets struck the Mezzeh air base and a branch of the Scientific Studies and Research Center in Damascus.

As well, Israeli forces seized two vital border areas on December 8 — the buffer zone on the Golan created by a 1974 agreement between Israel and Syria and the Syrian side of Mount Hermon. These deployments are defensive and temporary, Israel said.

In retrospect, the end of the Assad era in Syria may really have begun on October 7, 2023, when Hamas terrorists attacked communities in southern Israel, killing roughly 1,200 civilians and soldiers and kidnapping 251 Israelis and foreigners.

This unprecedented massacre, the worst single day in Israel’s history, unleashed a ferocious Israeli armed response that ignited the wars in the Gaza Strip and Lebanon and Israel’s direct military clashes with Iran.

On December 8, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu claimed credit for starting this startling chain of events.

“This is a historic day in the history of the Middle East,” he said during a visit to Mount Bental on Israel’s border with Syria. “The Assad regime was a central link in Iran’s axis of evil, and now it has fallen. This is a direct result of the blows we have inflicted on Iran and Hezbollah, the main supporters of the Assad regime.”

Netanyahu’s explanation sounds reasonable enough.

Assuming he is correct, Israel is likely to grow stronger in the wake of Assad’s downfall. Turkey, a supporter of the rebel cause, may equally benefit from the upheaval in Syria.