Justice is elusive in Argentina.

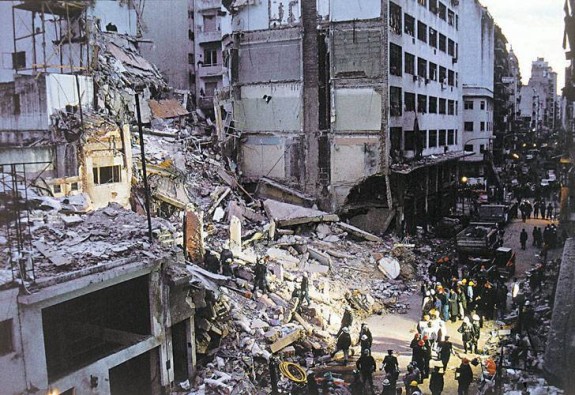

The bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires nearly 26 years ago, the worst antisemitic crime since the Holocaust and the most deadly act of terrorism in Argentina, remains murky to this day.

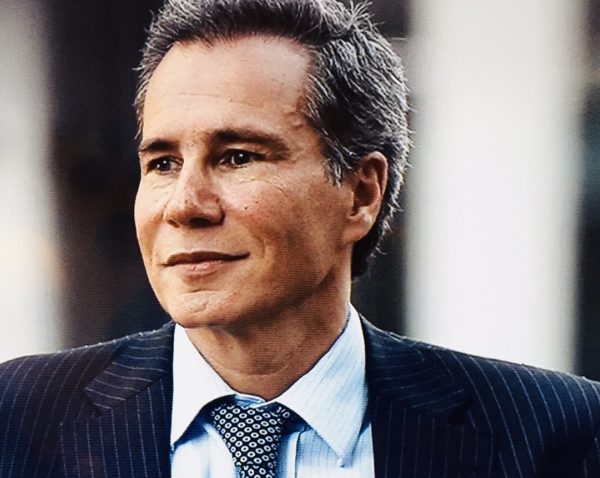

Alberto Nisman, the Jewish Argentinian prosecutor assigned to the case, was found dead in his apartment on January 18, 2015, just hours before he was due to present his findings to Congress. His death was initially regarded as a suicide, but a federal court later ruled he had been murdered. The murderer, or murderers, have yet to be caught.

The mystery surrounding these interlocking events lies at the core of The Prosecutor, The President And The Spy, a six-part Netflix documentary directed by Justin Webster that often unfolds like an espionage thriller. A British filmmaker, he bombards viewers with a mountain of facts, theories and interviews, but at the end of it all he’s no closer to solving these incredibly complex and convoluted cases.

On the morning of July 18, 1994, the building housing the headquarters of the Argentine Jewish Mutual Association (AMIA) was bombed, killing 85 people and wounding about 300. The blast took place more than two years after Israel’s embassy in Buenos Aires was attacked, resulting in the deaths of 29 Israeli diplomats and local employees. The Lebanese militia, Hezbollah, supposedly carried out the operation in retaliation for separate Israeli air strikes in Lebanon that killed its secretary-general, Abbas Musawi, in February 1992 and 26 of its recruits at a training camp in June 1994.

In 2006, Nisman accused Iran, Israel’s foremost enemy, of planning and financing the AMIA bombing and Hezbollah of perpetrating it. But Nisman’s efforts to prosecute Iranian officials, including Iran’s former president, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and the Iranian cultural attache at Iran’s embassy in Buenos Aires, Mohsen Rabbani, were short-circuited by the Argentinian government. This happened when President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and Foreign Minister Hector Timerman agreed to sign a memorandum with Iran establishing a joint “truth commission” to investigate the bombing.

Subsequently, de Kirchner was charged with covering up Iran’s role in the bombing in exchange for Iranian trade and oil benefits. She dismissed the allegation, blaming disgruntled Argentinian intelligence agents. In 2017, she was formally indicted in connection with the alleged coverup. Despite the indictment, Argentina’s current president, Alberto Fernandez, chose her as his vice-president.

Webster plunges headlong into this whirlpool of accusations and counter-accusations by means of interviews with Nisman, de Kirchner and Timerman and a plethora of Argentinians who had a professional interest in both cases. Among them are local journalists who covered the story; two FBI agents who followed it from their base in Buenos Aires ; Viviana Fein, a prosecutor who investigated Nisman’s death; Antonio (Jaime) Stiuso, a former high-ranking official in the secret service who was in charge of the first investigation of the AMIA bombing; Sandra Arroyo Salgado, Nisman’s ex-wife and a prosecutor herself, and Diego Lagomarsino, a computer specialist who befriended Nisman and lent him a pistol on the eve of his death.

Webster jumps between the bombing and Nisman, drawing out an avalanche of minor and major details.

Diana Wassner, a member of Buenos Aires’ Jewish community, recalls that the massive explosion that brought down the AMIA building at 9:53 a.m. could be heard 20 city blocks away, and that flying debris landed as far as 10 blocks from the epicenter.

Nisman concluded that Ibrahim Berro, a member of Hezbollah, was the driver of the explosives-filled suicide van he detonated on that fateful day. His DNA was found in the wreckage of the vehicle. Declared a “martyr” by Hezbollah, he was buried with full honors in Lebanon.

Despite Nisman’s zeal to break open the case, it languished. Nestor Kirchner, de Kirchner’s late husband, is quoted as saying that the government was not really interested in resolving it.

Iran vigorously denied its involvement in the bombing and made that clear to Timerman, who claims he did “everything” to get to the bottom of both cases. Nisman, believing that de Kirchner was shielding Iran, was convinced that justice would prevail, and that he would either lock her up or send her into exile. “I have something huge,” he told a friend.

Nisman’s bloodied corpse was found on the floor of his bathroom, a blood-stained handgun next to him. Fein, the first government official who saw his body, says, “We could be talking about suicide.” Yet not a trace of gunpowder was detected on Nisman, categorically ruling out the possibility he had killed himself.

Nisman’s friends and allies are absolutely certain he was murdered, and Stiuso agrees with that supposition.

Whatever the truth may be, Webster provides no compelling evidence to bolster the flimsy argument that Nisman committed suicide. Nor does he furnish viewers with plausible leads regarding his assassin or assassins.

Although The Prosecutor, The President And The Spy is informative, it is not razor sharp in its focus and imparts far too much information, some of which is frankly extraneous. These are flaws that exact a toll on this ambitious documentary.