The Red Army liberated Nazi extermination camps and freed the greatest number of Holocaust survivors, but its unsurpassed record of liberation loomed as a taboo topic in the now-defunct Soviet Union until the late 1980s, three scholars told an academic forum in Toronto yesterday during Holocaust Education Week.

The role played by the Soviet Union in freeing Nazi camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau and Treblinka and liberating thousands of Jewish prisoners has been underplayed due to Moscow’s ambivalent policies before and after World War II, said Doris Bergen, the Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe professor of Holocaust Studies at the University of Toronto.

By her reckoning, the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin was both an ideological foe and partner of Nazi Germany. The two countries signed a non-aggression pact a week before the outbreak of the war, but after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, they were bitter and irreconcilable enemies.

Upwards of two million Soviet Jews were murdered by the Nazis, but about 500,000 Jews found refuge behind Red Army lines in Central Asia and Siberia, she noted.

And while there were a high proportion of Jewish officers in the Red Army, Soviet Jews were persecuted and marginalized by the Soviet state in the wake of the war, Bergen added.

The Soviet Union was thus “a liberator and an oppressor” in the eyes of Jews, she observed.

Zvi Gitelman, a professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan and an expert on Soviet Jews, hewed to the same theme.

The Red Army’s role in the liberation of Nazi camps and Jewish survivors was a “non-subject” in the Soviet Union until the era of glasnost from the mid-1980s onward, he said.

“It’s still a politically-charged issue in Russia and the Baltics,” he went on to say.

Anna Shternshis, the Al and Malka Green associate professor of Yiddish Studies at the University of Toronto, said Red Army soldiers first stumbled upon evidence of Nazi atrocities in Ukraine in 1943 when they found mass graves and rotting corpses in fields. The Soviet media carried reports of Nazi massacres as early as 1941, when Einsatzgruppen mobile killing squads murdered Jews in massive shooting sprees and pogroms.

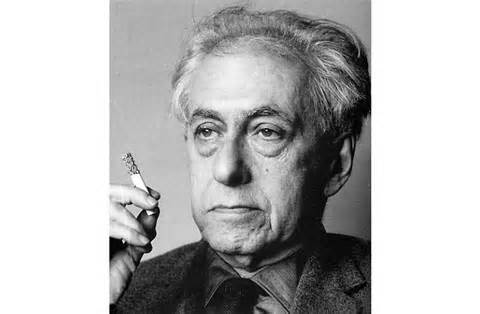

Two of the Soviet Union’s best known war correspondents, Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman, wrote impassioned stories about Nazi war crimes.

Gitelman pointed out that the story of German atrocities was not exclusively a Jewish story, given that 18 million Soviet citizens and eight to nine million Red Army soldiers lost their lives during the war. Red Army soldiers instinctively understood that German fascism was an “imminent threat” to their families.

In general, Jewish Red Army soldiers fought with increased ardor after learning about Nazi crimes, he said.

Some sought revenge and took pride in the number of Germans and local collaborators they had killed, Shternshis noted. Vengeance was a leit motif played up by the Soviet press.

Some non-Jewish Soviet soldiers displayed a flippant attitude toward the mass murder of Jews, while still others were indifferent, she said.

Their presentations were sponsored by the Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Center, UJA Federation of Greater Toronto, the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Arts and Science and the Anne Tanenbaum Center for Jewish Studies.