The United States and one of its key allies in the Middle East, Turkey, remain at odds over an array of contentious issues.

The rift between Washington and Ankara may widen during the presidency of Joe Biden, who has yet to make a much-awaited phone call to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whom he previously described as an “autocrat.”

Biden is bound to be more critical of Erdogan than his predecessor, Donald Trump, who admired the Turkish leader as a populist strongman and usually shielded him from criticism.

Turkey, whose membership in NATO protects the western alliance’s eastern flank on the Russian border, triggered tensions by buying the made-in-Russia S-400 surface-to-air missile system in 2017 over strenuous objections from the United States. Turkey further irritated the United States by testing it. Turkey turned to Russia after Washington’s refusal to sell it Patriot missiles.

The Trump administration claimed that the S-400 was a threat to U.S. interests, allowing Russian access to the Turkish armed forces and Turkey’s defence industry and endangering the security of American personnel and military technology.

In short order, the United States cancelled a contract to deliver F-35 fighter jets to Turkey, fearing that Russia could exploit their capabilities. Turkey, in the meantime, hired an American law firm to lobby for its return to the F-35 program.

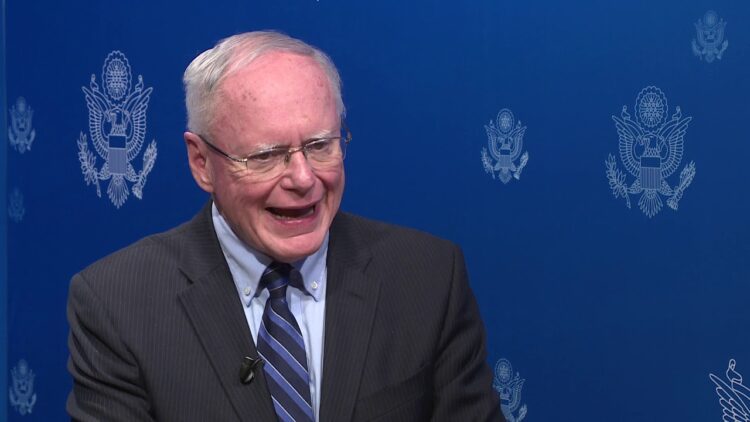

Last December, Washington imposed limited sanctions against Turkey’s military acquisitions organization. “This is not a step we have taken lightly, or certainly quickly,” said Christopher Ford, the then U.S. assistant secretary of state for international security. “We tried very hard to give Turkey every opportunity to find a better way forward, and it hasn’t done so.”

Washington has also criticized Turkey for its human rights record, having condemned the prolonged arrest of Turkish human rights activist Osman Kavala and the incarceration of Turkish journalists who’ve offended the government. In response, Turkey has told the United States to mind its own businesses and stop interfering in its internal affairs.

Washington has also blasted Turkey’s military operations against U.S.-backed Kurdish forces in northern Syria. Turkey, for its part, has lambasted the United States for supporting the Syrian Democratic Forces, an umbrella group in Syria it has branded as a terrorist organization.

Turkey, in turn, has accused the United States of sheltering Fethullah Gullen, a Turkish cleric whom it accuses of having masterminded the failed coup against Erdogan in the summer of 2016. Two hundred and fifty people were killed and more than 2,500 were wounded before the uprising was suppressed.

Last month, Turkish Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu resurrected this issue. “It’s plain as day that America was behind the July 15 coup attempt,” he said, adding that Gullen’s network carried it out at the behest of the United States.

The U.S. State Department promptly rejected Soylu’s allegation, but public opinion polls indicate that most Turks are convinced that the U.S. was involved in the putsch.

Despite their differences, Erdogan seeks better bilateral relations with the United States. “We believe our common interests with America far outweigh our differing opinions,” said Erdogan in February.

Shortly after the U.S. presidential election, Erdogan sent Biden a letter of congratulations. “I believe that the strong cooperation and alliance between our countries will continue to contribute to world peace, as it has until today,” he wrote.

Turkey, however, is standing firm on its acquisition of the S-400. “Turkey will never refrain from taking the necessary measures to safeguard its national security,” the Foreign Ministry said. Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu added that U.S. sanctions “are not measures that will shake us to the core or impact us very much.”

Turkey’s minister of defence, Hulusi Akar, struck the same defiant tone, saying that a solution to this problem cannot deprive Turkey of the S-400.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has waded into the dispute as well. During his Senate confirmation hearings, he questioned Turkey’s reliability. “Turkey is an ally that in many ways … is not acting as an ally should,” he said. “And this is a very, very significant challenge for us. ”

In his first face-to-face meeting with Cavusoglu on March 25, in Brussels, Blinken called on Turkey to ditch the S-400 and warned him of the likely consequences.

Blinken’s view has been echoed in the U.S. Congress.

Democratic and Republican leaders in the House of Representatives’ Foreign Affairs Committee have urged Ankara to end its “provocative behavior” so that the United States and Turkey “can once again enjoy a close and cooperative relationship.”

Turkey’s acquisition of the S-400 “undermines” NATO, they’ve charged. And they have have warned Turkey that its attacks against the Syrian Democratic Forces risk reversing “critical gains” forged by the United States against the Islamic State organization.

Turkey’s ties with Hamas have also been criticized in Congress.

Last month, more than half of the members of the Senate signed a letter urging Biden to pressure Erdogan to improve Turkey’s human rights record. They allege that Erdogan has “marginalized domestic opposition” and “silenced or coopted critical media outlets.”

Although Turkey’s value as a U.S. ally has eroded, no one underestimates its strategic importance. As James Jeffrey, the former U.S. ambassador to Turkey, said recently, “Given Turkey’s size, location, economic and military power, and the pro-Western sentiments of the population — if not its president — does it make sense to sideline Turkey and push it into the Russian camp?”

In Jeffrey’s view, Turkey — which is at loggerheads with Russia over conflicts in Syria and Libya — is a critical Western ally in Iraq and Afghanistan and a bulwark against Iran’s advances in the Middle East.

These factors notwithstanding, the United States’ relations with Turkey remain fractured and may not improve any time soon.