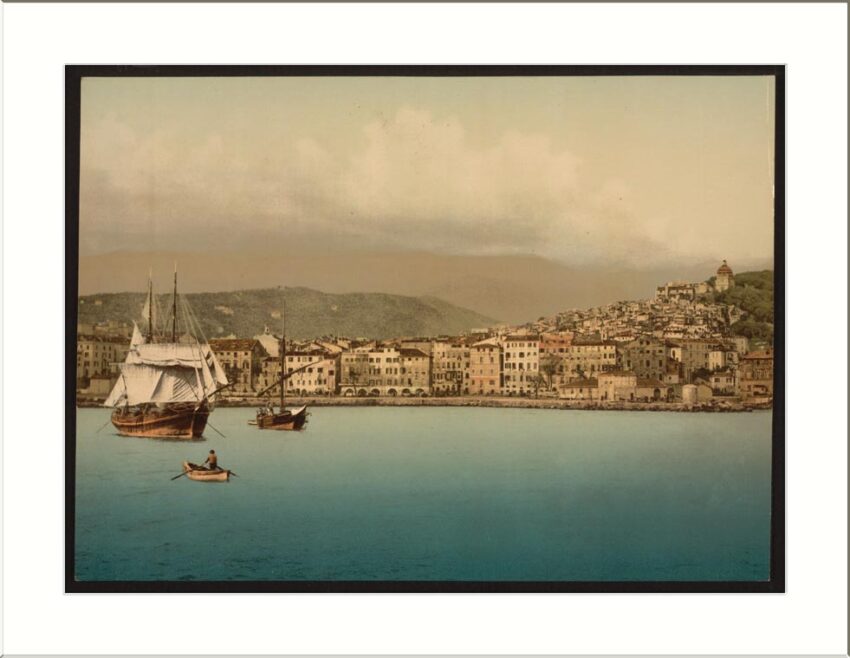

One hundred years ago this month, the map of the Middle East was radically redrawn by the major powers at a long-forgotten summit in a pretty resort town in northwestern Italy.

The San Remo Conference, which took place in 1920 between April 19-26 at the Villa Devachan, officially ratified the breakup of Turkey’s Ottoman Empire into League of Nations mandates, thereby creating a new international order in the region.

Britain would administer Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine, which included Trans-Jordan, and France would be charged with administering Syria and Lebanon.

An argument can be made that the conference was an exercise in imperialism, that it was nothing less than a mechanism for Britain and France to expand their colonial empires at the expense of Turkey and the Arab world.

But the hard truth is that the mandates were established with the ultimate intention of guiding Jews to self-governance in Palestine — the Jewish ancestral homeland — and Arabs to statehood in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Trans-Jordan, which later became known as Jordan.

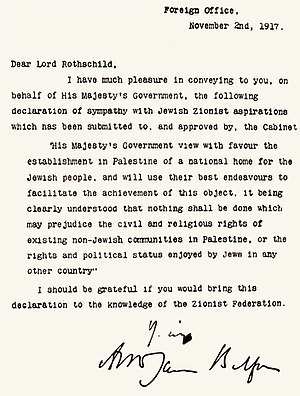

For the Zionist movement, the conference was a milestone inasmuch as it instructed Britain to implement the Balfour Declaration. Taking the form of a brief letter sent to Zionist leader Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild by British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour on November 2, 1917, it viewed with favor the creation of a “national home” for the Jewish people in Palestine on condition that the civil and religious rights of its Muslim and Christian inhabitants remained intact.

The conference effectively recognized the Jewish people’s historical connection to, and right of self-determination in, Palestine, the ancient Land of Israel.

The resolutions adopted by the conference were incorporated into international law by the Treaty of Sèvres in August 1920 and unanimously approved by the League of Nations several years later.

The conference was convened in the wake of World War I, which upended the territorial status quo in the Middle East.

The Ottoman Empire, based in Constantinople, encompassed much of the Middle East and a good chunk of the Balkans. Palestine, having been overrun by invaders ranging from the Persians to the Romans, was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1516.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the Ottomans aligned themselves with Germany and its allies. As battles on the Middle Eastern front raged, during which the Turks steadily lost ground to British and allied forces, Britain and France cooked up plans to divide up this vast polyglot empire.

The first step in that process occurred in 1915, when Henry McMahon, the British high commissioner in Egypt, reached a momentous understanding with the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali. In exchange for instigating a revolt against the Turks, Britain held out the promise of independence and sovereignty to the Arabs. T.E. Lawrence, a British army intelligence officer who would be dubbed Lawrence of Arabia, was directly involved in this military campaign.

In 1916, Britain and France signed the secret Sykes-Picot agreement carving up spheres of influence in the Middle East. Britain would be granted control of southern Palestine, Trans-Jordan and southern Iraq and be given port privileges in Haifa and Acre. France would receive Syria and Lebanon, as well as parcels of land in southwestern Turkey and northern Iraq.

As 1917 dawned, British and Australian troops under the supreme command of General Edmund Allenby began driving the Turks and their German advisors out of Palestine, which by then was populated by a minority of 80,000 Jews in a population of some 500,000 Arabs.

Most Jews had been uprooted from Palestine by the Romans, but in the late 19th century the eruption of pogroms in the Russian Empire impelled a small number of Eastern European Zionists to settle in rudimentary farming communities in Palestine.

Theodor Herzl, an assimilated Austrian Jewish journalist born in Budapest, was the founder of political Zionism, which fed on the millenarian Jewish attachment to Palestine. He was converted to Jewish nationalism while covering the trial of Alfred Dreyfus, a French army officer of the Jewish faith who had been falsely convicted of treason in a case that reeked of antisemitism, which persisted in France a century after Jews were formally emancipated.

At the first Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897, delegates voted for a resolution backed by Herzl — the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine. In a remarkably prescient comment, Herzl predicated that Jewish statehood would be achieved within 50 years.

With the Balfour Declaration, the fulfillment of the Zionist dream reached unprecedented heights. Zionist diplomacy, spearheaded by a Russian-born chemist living in Britain named Chaim Weizmann, was successful in convincing the British government that its strategic interests converged with the Zionist project in Palestine.

By that juncture, France had warmed up to Zionism. Five months before the advent of the Balfour Declaration, the secretary-general of the French Foreign Ministry, Jules Cambon, issued a letter endorsing a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

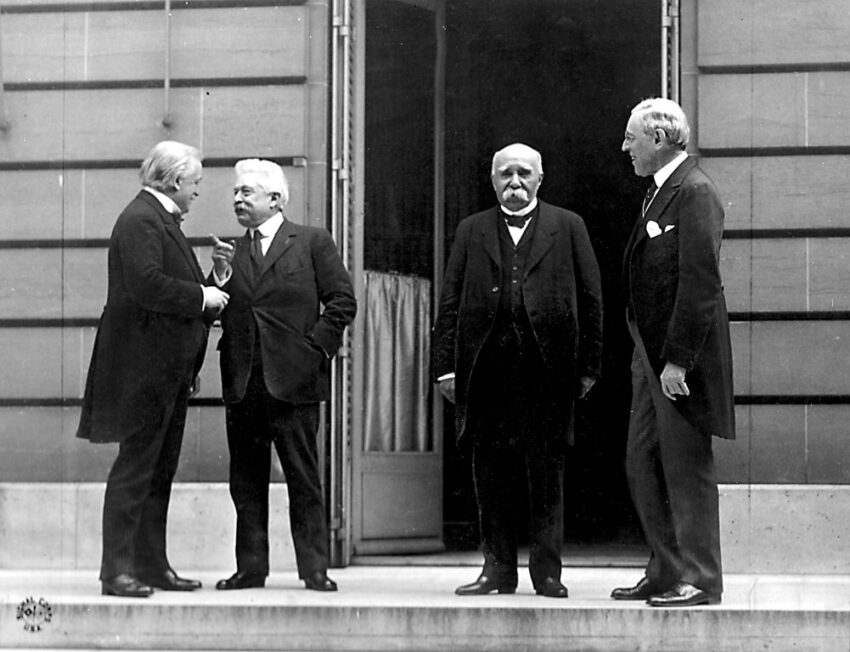

In 1918, France’s prime minister, Georges Clemenceau, acceded to a request by his British counterpart, David Lloyd George, that Palestine should be handed over to Britain in exchange for its recognition of France’s claim to Syria and Lebanon. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, France announced it would not stand in way of the formation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

Yet opposition to Zionism was building to a crescendo, particularly among the Palestinian Arab residents of Palestine. Their cause was keenly supported by Arabs throughout the Middle East.

Fierce opposition to Zionism was detected by the 1919 King-Crane Commission, which was dispatched to Palestine by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to gauge local public opinion regarding the possibility of continued Jewish settlement.

As a direct result of the Paris Peace Conference, the Supreme Council of the Principal Allied Powers (France, Britain, Italy and Japan, with the United States present as an observer) convened in San Remo to ratify the allocation of mandates in the Middle East.

The chief participants at the conference were the prime ministers of Britain, France and Italy, respectively David Lloyd George, Alexandre Millerand and Francesco Nitti. Japan was represented by its ambassador, Keishiro Matsui.

They settled the affairs at hand within a week, setting into motion an historic process that intrinsically reshaped the geopolitics of the Middle East.

And yet this seminal conference gradually faded into the mists of obscurity, overtaken by subsequent political earthquakes. As the Israeli historian Ephraim Karsh writes, “There is probably no more understated event in the history of the Arab-Israeli conflict than the San Remo Conference.”