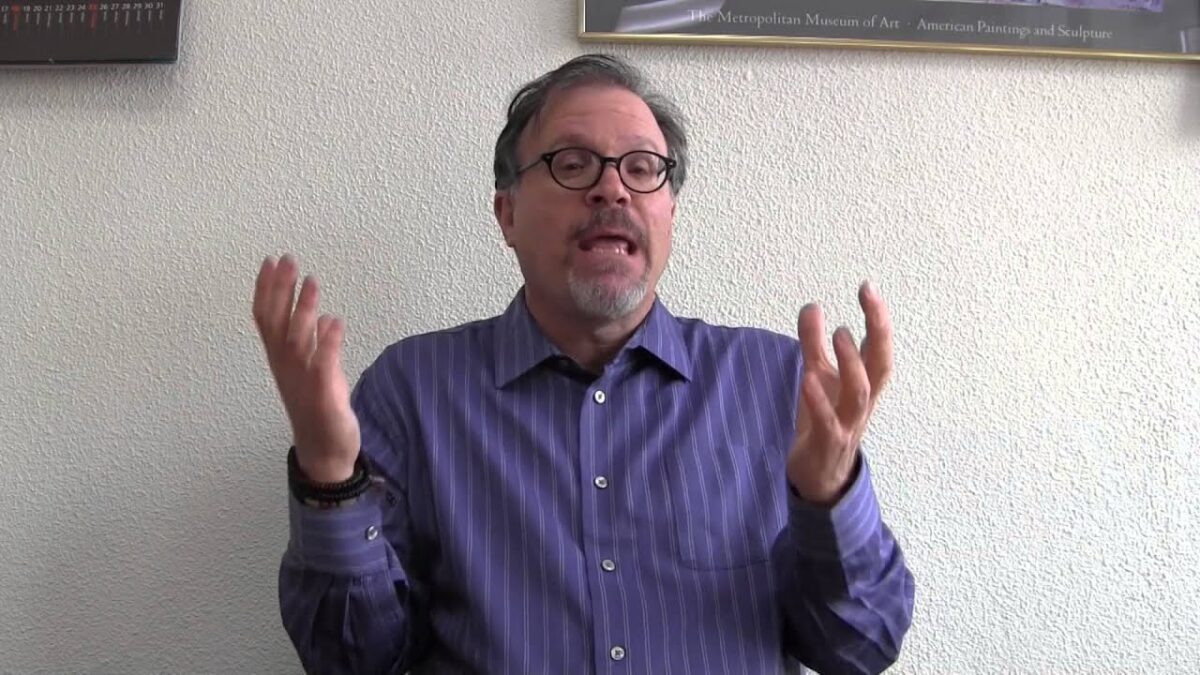

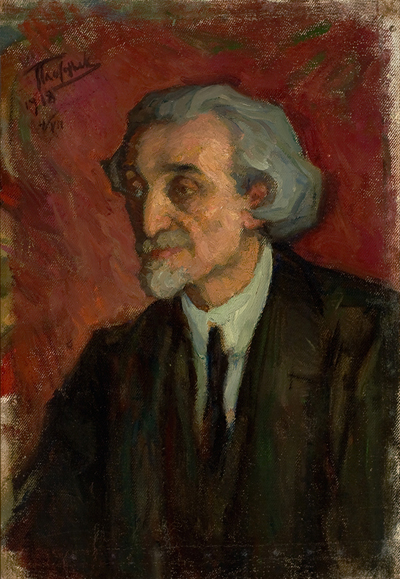

Ilan Stavans compares his lengthy trip to Latin America a few years ago to an ethnographic expedition undertaken by the fabled folklorist S. Ansky to Eastern Europe in the second decade of the last century. In his Yiddish-language book, The Enemy At His Pleasure, Ansky offered an acute analysis of Jewish life in Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova and layered it with pungent personal observations.

Stavans, in The Seventh Heaven: Travels Through Jewish Latin America (University of Pittsburgh Press), emulates Ansky in many respects. A Latin American Jew of Polish descent who immigrated to the United States in the mid-1980s, he spent four years on the road, plumbing the depths of countries like Argentina, Mexico and Cuba.

“The journey had been as much about the history of Jewish Latin America as it had been a quest of self-discovery,” he writes in this impressionistic and appealing travelogue.

I was drawn to Stavans’ account because my travels have taken me to Latin America and the adjacent Caribbean islands. During a nearly 40-year period, I have visited Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, El Salvador, Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, Jamaica, Cuba and the Dominican Republic. While touring these countries, I usually explored their Jewish communities, most of which go back centuries.

Demographically, they’re minuscule. “Yet as a conglomerate they represent the third largest concentration of Jews worldwide, after the United States and Israel and before France and Canada,” Stavans says.

Latin America is important insofar as Israel is concerned. Thirteen nations, including Brazil, Venezuela and Ecuador, voted for the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan in favor of establishing a Jewish state. Some, like Chile, Mexico and Colombia, abstained. Only Cuba voted against the resolution.

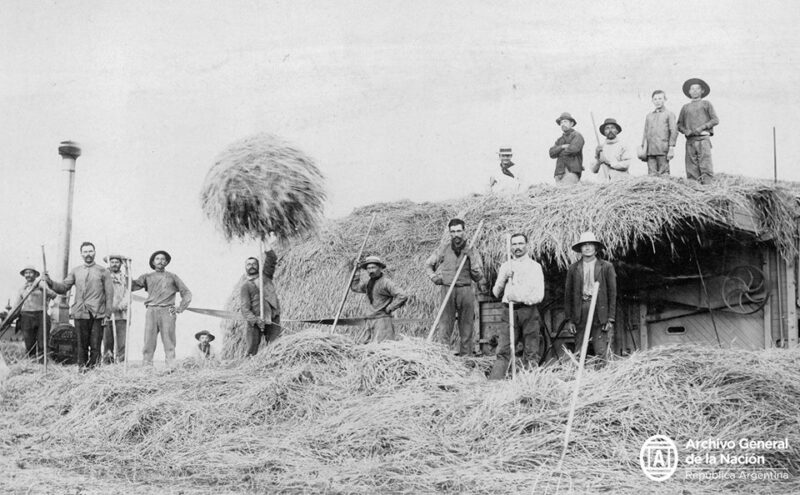

Stavans, who was raised in the Colonia Copilco neighborhood of Mexico City, begins his trip in Argentina, a nation of immigrants. “Aside from the Spanish, British, Italian and Portuguese, newcomers from Germany, Scandinavia, Poland and Russian have settled in Argentina. More recently, people from Africa, Korea and the Middle East have also come in,” he writes.

In the 19th century, as he notes, 6.6 million immigrants poured into Argentina, including substantial numbers of East European Jews fleeing persecution and pogroms. Only the United States surpassed Argentina in terms of its openness to mass immigration.

During the 1960s, Argentina was home to 300,000 Jews and had the largest Jewish community in Latin America. But by 2015, the number had fallen to between 180,000 and 220,000.

Stavans — a professor of humanities and Latin American and Latino culture at Amherst College — wanders around El Once, a crowded commercial district in Buenos Aires commonly identified with Argentinian Jews. He points out that the city once nurtured a vibrant Yiddish press, and that some tangos and traditional Argentine songs were composed in Yiddish.

Jews have fared well in Argentina, but close to 100 were killed in El Once in 1919 during an anti-immigrant protest and labor dispute that, some historians claim, was actually a pogrom, the first and only one in Latin America.

And on July 18, 1994, a Jewish community building in Buenos Aires was bombed, killing 85 people, in the worst antisemitic outrage since the Holocaust. It is widely believed that Hezbollah, in conjunction with Iran, were behind the attack.

“Antisemitism in the Americas is as old as modernity,” he says. “Its sources have changed over time. In certain periods, it has been sponsored by the Catholic church. In others it has sprung from the dissemination of stereotypes in popular culture.”

During the so-called Dirty War, when the Argentinian government was embroiled in a battle against left-wing guerrillas, a disproportionate percentage of the victims were Jews. Stavans’ guide in Buenos Aires ascribes this death toll to the widespread perception that “many Jews were left-leaning” and had been involved in “anti-military activities.”

Due to the efforts of the Jewish Colonization Association, thousands of Russian Jews were settled in pampas towns such as Moisesville and Villa Dominguez and earned a living as small farmers and merchants. A grandson of one of these pioneers, Jose Nestor Peckerman, was the coach of Argentina’s and Colombia’s national soccer teams. Contrary to myth, there were never any Jewish gauchos (cowboys) in the pampas.

After making a few observations about the alleged Jewish origin of legendary Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, Stavans invites a reader to his boyhood neighborhood. Once bucolic, it has degenerated into a congested and ugly district. Not surprisingly, he feels disconnected from it.

He visits Casa Trotsky, where the former Soviet communist leader Leon Trotsky lived until his assassination in 1940. “Nowhere in the entire museum was there any mention that Trotsky was Jewish. Granted, it wasn’t an aspect that he himself stressed.”

Stavans devotes a few pages to Indian Jewish converts to Judaism. “There are about a dozen fringe communities of this kind in Latin America, if not more,” he says. He cites, among others, the descendants of Moroccan Jews who were active in the rubber trade and who married Amazonian women. In general, Indian claims to being Jewish have been rejected by mainstream Jews.

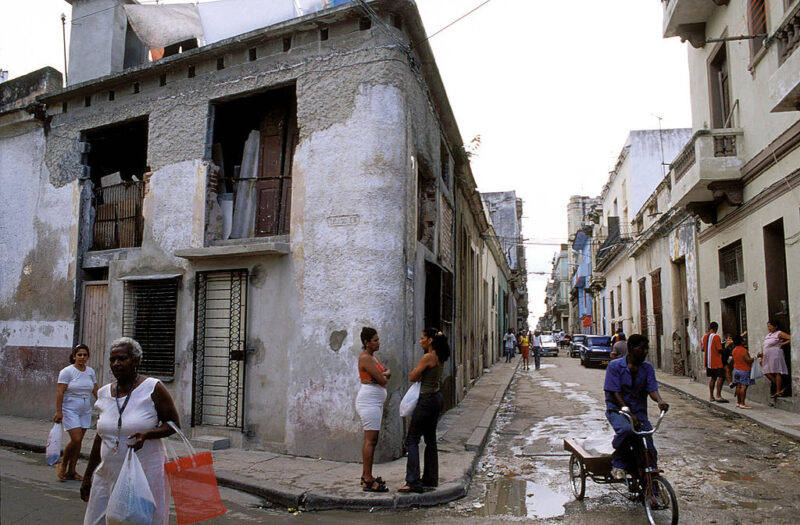

Cuba, a port of arrival and transit for European merchandise en route to Latin America, attracted newly-converted Jews to Christianity in the colonial era and American, European and Sephardic Jews in the 20th century. The majority of Cuban Jews emigrated in the wake of Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution. Those who remained behind were invariably converts to Judaism or the products of mixed marriages who regard themselves as Jews.

Cuba broke diplomatic relations with Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, but welcomes Israeli tourists.

Stavans meets a middle-aged Jamaican woman in Old Havana and their meeting leads to a conversation about Jews in Jamaica. Some of the oldest tombstones on the island date back to the 17th century and are engraved with Hebrew letters. Yaakov Kuriel, a Jewish pirate based in Jamaica, harassed Spanish vessels. At the end of this life, he went to Ottoman Palestine and became a Kabbalist. He died in Safed in 1572.

Recalling trips to Venezuela in 2005 and 2013, Stavans dredges up memories of Hugo Chavez’s anti-Israel rhetoric, which sometimes spilled into outright antisemitism, driving out thousands of Jews.

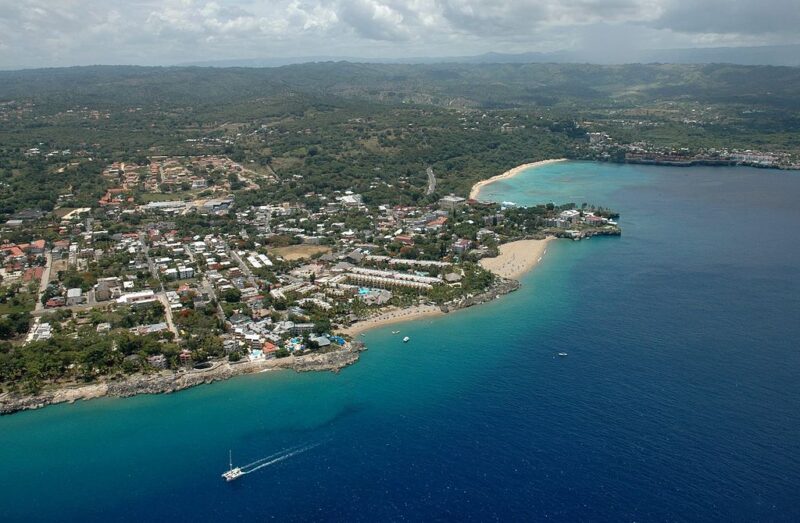

In the Dominican Republic, he focuses on Sosua, a Jewish colony that was populated, in the main, by German and Austrian Jewish refugees fleeing Nazism. Rafael Trujillo, the island’s dictator from 1930 to 1961, invited Jews to “whiten” its population. Hundreds accepted his invitation.

While in Montevideo, Stavans learns that, in per capita terms, Uruguay is the country from which the greatest number of Jews have made aliyah. They arrived in Israel in the 1970s and between 1998 and 2003, when Uruguay was gripped by financial troubles.

Arabs have migrated to Latin America in droves, says Stavans. By all accounts, 17 million to 30 million ethnic Arabs live in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Chile. Brazil has more people of Lebanese descent than Lebanon itself, while Chile has more Palestinians than anywhere except the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Such are the nuggets that turn up in The Seventh Heaven.