An avalanche of books has roared off the presses since the outbreak of the Six Day War on June 5, 1967, yet Guy Laron’s new paperback edition of The Six Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East (Yale University Press), a bracing account of its causes, offers fresh insights into a seminal conflict that tripled Israel’s size and redrew the map of the Middle East.

Laron, a senior lecturer in international relations at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, focuses on several key issues — Israel’s intermittent clashes with Syria as a prelude to war, the Soviet Union’s, Egypt’s, Jordan’s and the Palestinians’ respective roles in fomenting it, the United States’ attempts to head it off, and Israel’s territorial designs.

The immediate root cause of the war turned on Israel’s border dispute with Syria within the contested demilitarized zone, which was established in the wake of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Consisting of about 200 square kilometres, the zone was divided into three areas to the east and northeast of the Sea of Galilee.

The Syrian position was that Israel should not have a right of access to it until a final agreement concerning its status was signed. Israel’s interpretation was diametrically different: Israel had full sovereignty over it and could do as it pleased. The issue was complicated by the fact that Israeli and Syrian farmers owned land within the zone.

The disagreement was serious enough to spark periodic air and land battles between Israel and Syria from the 1950s onward. The Syrian army on the Golan Heights would shell Israeli settlements, prompting swift reprisals by Israel’s air force. On April 7, 1967, the situation spun out of control when Israeli aircraft downed six Syrian MiGs in a dogfight. Subsequently, the Soviet Union — Syria’s ally and arms supplier — circulated a false rumor that Israel was massing forces on its northern border to attack Syria. The Soviet ambassador in Damascus, Anatoli Barkovski, conveyed that message to Syrian Foreign Minister Ibrahim Makhus, and it inflamed the region.

Before the eruption of these border incidents, tensions were already boiling over. Arab states were outraged by Israel’s plan to divert regional waters for its pipeline from the Sea of Galilee to the Negev Desert. Israel was furious over Syria’s retaliatory water diversion plans and its support of Fatah, a Palestinian guerrilla group opposed to Israel’s existence.

In 1965, Fatah launched the first of a series of attacks, planting explosives near water pipelines, pumps, warehouses and power plants. Fatah also began mining roads, highways and railway tracks. Fatah’s terrorism stoked Israeli anxiety and anger.

On the second day of the war, Syria launched a half-hearted offensive that was easily blocked by Israel. Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Dayan was initially loathe to launch a counter-attack, but changed his mind during the final hours of the war. Laron discloses that Syria’s finest fighting forces remained in Damascus to keep the Baathist regime safe from its internal enemies.

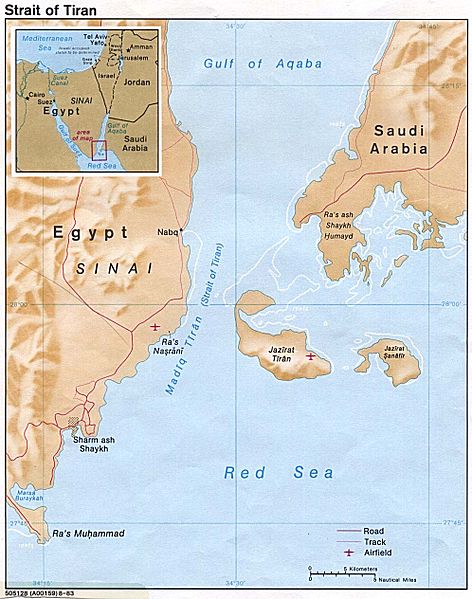

Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, attempting to gain the upper hand over Syria in the struggle for regional supremacy, fanned the flames of war as well, says Laron. Nasser not only demanded the withdrawal of United Nations peacekeeping troops from the Sinai Peninsula, but closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, thereby committing an act of war under international law.

According to Laron, Nasser backed away from an armed confrontation with Israel after closing the Straits of Tiran. While Egyptian Vice-President Abd al-Hakim Amer advocated an aggressive approach to Israel, Nasser was content with the status quo. In a bid to defuse the growing crisis, he asked Syria to rein in Fatah operatives on Syrian soil and informed Ahmad Shukeiri, the chairman of the PLO, that Egypt was not ready for a “liberation campaign.” Similarly, he told the United States he had no intention of waging war on Israel.

Israel did not buy his claims and attacked the Sinai, destroying the Egyptian army in a lightning campaign. A photograph of a long column of wrecked Egyptian armor in the Sinai pretty much told the story of Egypt’s ignominious defeat.

King Hussein of Jordan, who had been secretly meeting Israeli officials in the 1960s, assured Israel he would not permit Iraqi forces to enter his country and take up positions near the Israeli border. Nor would he allow the Palestine Liberation Organization to establish bases in Jordan. He retreated from his promises after an Israeli armored force struck the Jordanian village of Samu in 1966 in a reprisal that resulted in the deaths of 14 Arab Legion soldiers. On the eve of the Six Day War, Jordan signed a military treaty with Egypt. King Hussein later disclosed that the Samu raid convinced him that Israel was untrustworthy and that it coveted the West Bank.

As Laron suggests, Jordan’s hands were tied during the war. On the first day of hostilities, Eshkol wrote a letter to King Hussein imploring him to stay out of the war. But since an Egyptian general had been placed in charge of the Arab Legion, Jordan effectively lost control of its army and ignored Israel’s request. As a result, Jordan lost the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Laron points out that some high-level Israelis were in favor of a war. Much to his surprise, the Israeli prime minister, Levi Eshkol, discovered in 1963 that the chief of staff, General Tzvi Tzur, wanted to use the next war to expand Israel’s borders so as to achieve strategic depth. His deputy, Yitzhak Rabin, concurred, as did the commander of the Israeli Air Force, Ezer Weizman, who maintained that “the current borders and not sacred” and needed to be changed in the next war.

Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, had described the post-1948 borders as “unbearable.” Taking its cue from him, the Israeli army’s planning department drew up contingency plans for defensible borders. They were to run along geographic barriers such as the Golan in the north, the Suez Canal in the south and the Jordan River in the east. In the weeks prior to the war, however, Eshkol informed the Knesset’s foreign affairs committee that war should be avoided and that Israel should abide by the territorial status quo.

Eshkol’s dovish outlook was shattered by the Arab military buildup along Israel’s borders and the United States’ failure to reopen the Straits of Tiran.

As Laron indicates, Israel was well prepared for armed conflict: “Every maneuver, every battle plan had been drilled and redrilled for years.”

There was, he adds, no equivalent degree of planning and preparation on the Arab side. Why? To Laron, the answer is clear: “Arab armies were built to ensure the survival of the regime. They were better suited to serve as internal police than as a fighting force. The regimes that sustained these armies held loyalty in higher esteem than efficiency or battle readiness. The constant purges of officers — to deter coups — prevented the development of capable cadres.”

Laron’s analysis of the Soviet Union’s approach to Israel in the months and weeks prior to the war is illuminating.

Although the Soviet Union was one of the first countries to recognize Israel on a de jure basis, the Soviets were mainly interested in currying favor with the Arab world, while leaving bilateral relations with Israel on a minimal level. This was particularly true during the 1960s, when Soviet weapons sales to Arab states were booming.

Despite its vigorous pro-Arab policy, Moscow let it be known in Arab capitals that it supported Israel’s right to exist within secure borders. In March and April of 1967, the head of the foreign ministry’s Middle Eastern department, Alexei Shchiborin, conveyed that message to Israeli diplomats. He also informed the Israelis that Moscow sought peace and stability in the region and that one of its main objectives was dissuading its Arab allies from attacking Israel. Several days before the war, the Soviet ambassador to Israel, Dmitri Chuvakhin, urged Eshkol to do everything possible to avoid a war.

Nonetheless, the Soviets stirred the pot by telling the Syrians that Israel had deployed eight brigades near Syria in an operation to destroy Syrian military sites on the Golan.

Laron has an explanation for the sharp discrepancy in Soviet policy.

One faction of the Soviet regime, headed by Communist Party chairman Leonid Brezhnev and Defence Minister Andrei Grechko, adopted an aggressive policy toward Israel. Another faction, spearheaded by Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin and Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, hewed to a more accommodating position. Kosygin and Gromyko argued that diplomatic relations with Israel should be preserved, but hawks in the Politburo prevailed and the Soviet Union severed ties with Israel, much to its geopolitical detriment. More than two decades would elapse before they were restored.

Prior to the war, the U.S. State Department and the Pentagon regarded Israel as “a strategic pain in the neck rather than as a strategic asset,” says Laron. But thanks to its victory, Israel became a valuable U.S. ally. Israel’s new relationship with the United States took shape despite the USS Liberty incident on the fourth day of the war, during which Israeli aircraft accidentally strafed an American surveillance vessel, killing 34 U.S. sailors.

Laron has written an important book about the events leading up to the war. If you read it in conjunction with Six Days of War, Michael Oren’s excellent work, you will be all the wiser.