The specter of Islamic extremism haunts Europe.

For about the past decade, a succession of young European Muslims fired up by Islamic radicalism have carried out one terrorist assault after another — from the train bombing in Madrid in 2004 that claimed the lives of 191 Spanish commuters to the attacks on the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket in Paris in January that claimed the lives of 17 people.

These terrorist outrages have shocked and angered Europeans, frightened European Jews and laid bare a festering sore in Europe’s body politic: Muslim disaffection from host societies.

This phenomenon is rooted in a variety of factors.

Some Muslims have reacted against Islamophobic prejudice in an increasingly tight employment market. Other Muslims do not identify with the values and customs of the countries in which they live. Still others, particularly those who have flocked to the ranks of Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, are animated by the siren call of jihadism, which distorts Islam and taps into grievances associated with the long and often dishonorable history of Western colonialism in the Middle East.

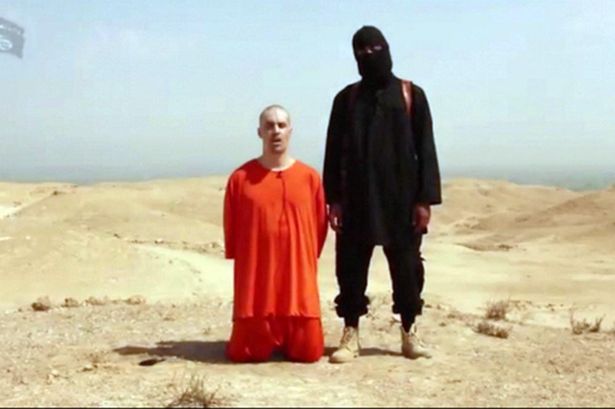

In recent months, the person who perhaps best exemplifies Muslim alienation has been Mohammed Emwazi, otherwise known as Jihadi John. A poster boy for the worst excesses of jihadism, Emwazi first came to notice last August in a gruesome video distributed by Islamic State.

Wearing a black balaclava and speaking with a foreign-inflected British accent, he was seen holding a knife over James Foley — an American journalist clad in an orange jumpsuit — before he brutally beheaded him. In subsequent videos, Emwazi could be seen posing in the same menacing position with yet more Islamic State prisoners who would be decapitated: the reporter Steven Sotloff and the aid workers David Haines, Peter Kassing and Alan Henning.

Emwazi, who remains at large, was born in Kuwait and grew up in northwest London, which has become something of a breeding ground for Islamic radicals. This neighborhood produced two of the Somali Muslim terrorists convicted of plotting to bomb London’s public transport system in the summer of 2005.

Emwazi was not one of the wretched of the earth. The scion of a middle-class family, he graduated from the University of Westminster with a degree in computer programming and seemed destined for a respectable career. It’s uncertain why he was radicalized, but his path to extremism went through Al Shabab, the Somali outfit which recently murdered scores of Christian students in Kenya, leaving Muslim students unharmed.

In countries like France, Belgium and Spain, the authorities have begun cracking down on jihadists like Emwazi.

France, still reeling from the attack on Charlie Hebdo carried out by the brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi and from the kosher supermarket rampage perpetrated by Amedy Coulibaly, has foiled five jihadist plots in recent months. The latest one was nipped in the bud a few days ago when a 24-year-old Algerian student was apprehended before he could attack a church near Paris.

France is on high alert. “We have never had to face this kind of terrorism in our history,” said French Prime Minister Manuel Valls on April 23.

Two months ago, French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve announced that a travel ban had been imposed on citizens suspected of engaging in terrorist activities. By all accounts, 1,400 French citizens belong to networks that have funnelled home-grown fighters to Syria and Iraq.

France has also closed charities, such as Pearl of Hope, charged with having sent funds to terrorist organizations.

Last week, Valls announced that 100 million euros will be allocated to programs and policies that monitor and combat racism and antisemitism. “Racism, antisemitism, hatred of Muslims, of foreigners … are increasing in an unbearable manner in our country,” he said. “French Jews should no longer be afraid of being Jewish, and French Muslims should no longer be ashamed of being Muslims.”

France is moving in the right direction, having recognized its duty to protect its 500,000 Jewish citizens and its five million Muslim citizens, the vast majority of whom are peaceful and law-abiding.

Belgium is also trying to curb Islamic radicalism. Recently, a judge ruled that Sharia4Belgium — which has sent young men to fight in Syria — is a terrorist organization and sentenced its leader, Fouad Belkacem, to 12 years in prison.

Belkacem was convicted of radicalizing Muslim youths and encouraging them to join salafist groups in Syria. It’s a serious problem, since returnees can turn murderously violent. Last May, Mehdi Nemmouche, a French national of Algerian descent who had fought with Islamic State in Syria, walked into the Jewish Museum in Brussels and shot and killed four tourists.

Spain is struggling with an identical problem.

On April 10, a month after the Spanish government disclosed it had dismantled a jihadist cell plotting attacks in Spain and neighboring nations, seven jihadists were imprisoned on charges of planning to bomb Jewish institutions and public buildings.

Many Islamic State recruits have entered Syria via Turkey, which until recently turned a blind eye to jihadists. Under U.S. pressure, Turkey — a NATO member — has taken steps to slow the flow. But James Clapper Jr., the director of U.S. intelligence, has expressed skepticism that the Turkish government will adopt tougher measures to seal its border altogether.

If Clapper’s assertion proves to be true, many more European jihadists will stream into Syria and Iraq via Turkey.