On June 27, 2007, Ashraf Marwan, an Egyptian hailed as one of Israel’s greatest spies, was killed when he fell to his death from a fifth-storey apartment balcony in central London. To this day, no one is certain whether he jumped or was pushed. Nor can one be absolutely sure whether he was an Israeli spy or an Egyptian double agent.

This complex issue is thoroughly examined in The Spy Who Fell To Earth, a fascinating British documentary by Thomas Meadmore now available on the Netflix streaming service. The film is based on an eponymous book written by Ahron Bregman, an Israeli researcher and writer living in London.

Bregman claims Marwan was a double agent, but his theory is hotly disputed by two former directors of the Mossad, Shabtai Shavit and Zvi Zamir, and by Yossi Melman, an Israeli investigative journalist who dismisses it as “bullshit.” As far as they’re concerned, Marwan was an Israeli super spy, Israel’s best ever Arab agent.

Claims by Egypt that Marwan was an Egyptian operative add another layer of complexity to this convoluted saga.

An immensely intriguing figure, Marwan was the son of an Egyptian army general, the son-in-law of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the president of Egypt from 1954 to 1970, and an aide to Anwar Sadat, Egypt’s president from 1970 to 1981. He moved in elite circles and had access to top secret information.

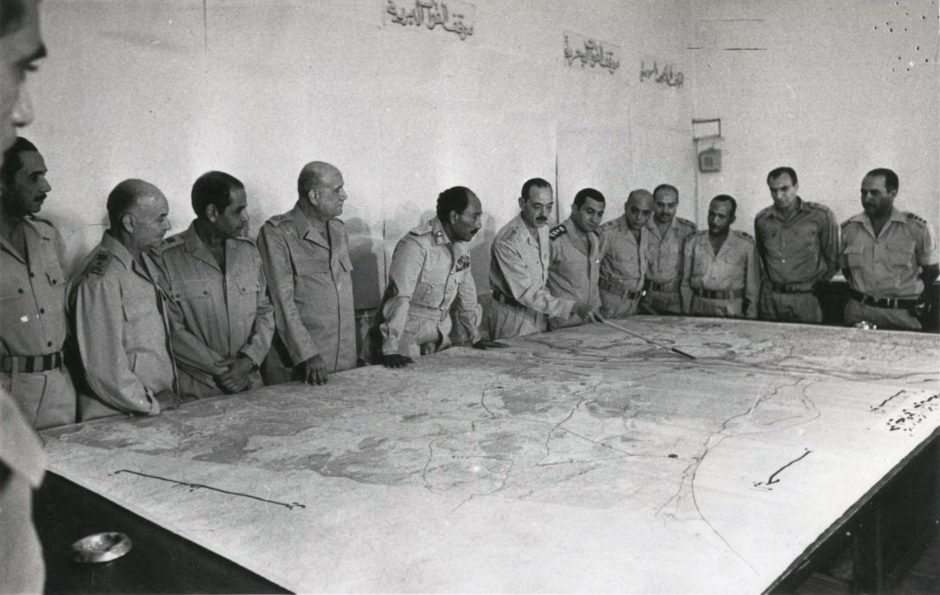

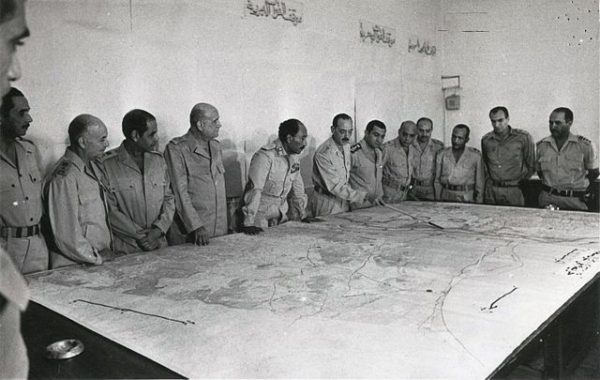

As Shavit describes him, Marwan was a “walk-in,” an intelligence source who voluntarily offered his services to Israel. Prior to the 1973 Yom Kippur War, he provided the Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, with Egypt’s war plans, thereby shaping its military strategy. Yet, paradoxically enough, Israel was not fully prepared for the coordinated offensive launched by Egypt in the Sinai Peninsula and by Syria on the Golan Heights on October 6, 1973. Israeli casualties were horrendously high, exceeding 2,000 killed in three weeks of warfare.

Marwan, born in 1944, married Nasser’s daughter, Mona, in 1966. Nasser, never really trusting him, gave him a minor position in his office. Feeling demeaned and punished, Marwan, accompanied by his wife, moved to London, where he continued his studies in chemistry. Appalled by Marwan’s high-living lifestyle, Nasser recalled him to Cairo.

Following Nasser’s death in 1970, Sadat, his successor, appointed Marwan to an important position in his presidential office. In the early 1970s, Marwan cold-called the Israeli embassy in London and offered Israel vital information about Egypt’s relations with its ally and arms supplier, the Soviet Union. Why did he allegedly betray his country? Bregman has no definitive answer, but to the best of his knowledge, Israel paid him $1 million, a substantial sum back then, for his services.

Meadmore claims that Marwan funnelled Egyptian battle orders to Israel. “It was beautiful information, really,” says Amos Gilboa, the former research director of the Mossad.

But according to Bregman, Marwan fooled Israel. “He was not the person Israelis thought he was,” he says.

Abdallah Hamouda, a former Egyptian intelligence operative, contends that Marwan was a double agent who answered to Sadat himself. “He was the best actor to portray the part,” he says, claiming that Marwan funnelled only partial and thus misleading information to Israel.

As a result, Egypt was able to surprise Israel on the first day of the war. Only 450 troops manned Israel’s Bar-Lev Line along the Suez Canal when 100,000 Egyptian troops attacked it. The disaster probably would have been far worse had Marwan not warned Israel about Egypt’s imminent onslaught.

Bregman argues that the director of Israeli military intelligence, General Eli Zeira, ignored Marwan’s warnings of an imminent Egyptian offensive to recapture the Sinai Peninsula. Zeira, forced to resign after the war, claimed in a book published in 1986 that Marwan was a double agent.

Zamir, who conferred with Marwan on the eve of Egypt’s offensive, is convinced he worked for no one but Israel. Such is Zamir’s confidence in Marwan that he wishes he could place a rose on his gravestone in Cairo. Shavit shares Zamir’s high opinion of Marwan.

The Egyptians think otherwise.

Marwan’s widow, Mona, believes he was an Egyptian hero murdered by the Mossad. Sadat honored Marwan after the 1973 war. His successor, Hosni Mubarak, called him a patriot of the highest order. Marwan’s funeral attracted the creme de la creme of Egyptian society. Strangely enough, though, the Egyptian government has not released evidence to substantiate its case that Marwan worked exclusively for Egypt.

Due to the sharply conflicting theories about his role as a spy, Marwan remains a mystery man, an enigma wrapped in a riddle, as The Spy Who Fell To Earth suggests.