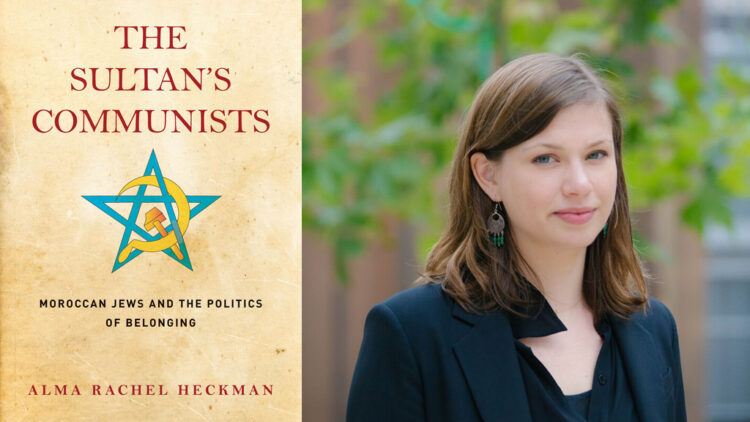

Alma Rachel Heckman has written an original and important book concerning the role that radicalized Jews played in Morocco’s struggle for independence from France and in newly independent Morocco. The Sultan’s Communists: Moroccan Jews and the Politics of Belonging (Stanford University Press) is billed as the first volume of its kind.

These Jews, members of the small Moroccan Communist Party, known as the PCM, were rebels in the truest sense of the word. Challenging the norms and traditions of a conservative Muslim Arab society, and deviating from traditional Judaism, they were outcasts in the Jewish community and the objects of persecution by the French colonial authorities and post-colonial Morocco.

Yet by the end of the last century, these pariahs were “hailed by the Moroccan monarchy itself (and) held aloft as national heroes and emblems of Morocco’s Jewish heritage,” writes Heckman, a professor of history and Jewish Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Until about 1945, Morocco was home to 250,000 Jews. But in the wake of Israel’s birth in 1948, the community declined as the vast majority immigrated to the Jewish state. Heckman explores the motivations of Jews who remained behind, the advent of Moroccan independence in 1956, and the Arab wars with Israel in 1967 and 1973. In doing so, she presents the heretofore untold story of Jewish radicals’ “involvement in Morocco’s national liberation project.”

With this path-breaking book, she challenges “standard narratives” of the Jewish past in Morocco. Pro-Zionist Moroccan Jews and Arab historians alike in Morocco have focused on emigration and “salvation” in Israel. “In contrast, this book examines the Jews who stayed in Morocco after independence and their political activism, which stood at the intersection of colonialism, Arab nationalism, and Zionism,” she writes. “This book is about a minority within a minority — Jews in the Moroccan Communist Party — and how they became the most famous of Moroccan Jews.”

Heckman singles out several figures in the PCM, which never had more than a few thousand members and was legalized only in 1968.

Edmond Amran El Maleh, a writer from the coastal city of Safi and one of its leaders, was prominent in the anti-colonial movement.

Abraham Sarfaty, a resident of Casablanca, underscored his Arab Jewish identify as a way of proclaiming his Moroccan patriotism.

Simon Levy, a proponent of a pluralistic Morocco, founded the Moroccan Jewish Heritage Foundation and Museum in Casablanca, a government-funded institution that expressed his belief that Jewishness and Moroccanness are inextricably bound up. Heckman credits him with the inspiration to write The Sultan’s Communists.

Leon Rene Sultan, born in Algeria, was a staunch believer in the universalist virtues of French republicanism and in the Zionist goal of a Jewish cultural renaissance.

Raphael Benarrosh, born in Meknes, served as a PCM lawyer prior to Moroccan independence.

Sion Assidon, hailing from Agadir, was ostracized by the Jewish community after being arrested in 1972.

As Heckman observes, Jewish participation in Communist politics was “a unique strategy to achieve normalization through conscious pariahdom.” But as she notes, “Moroccan Jewish Communists fought for an idealized Morocco that never quite came to fruition.”

Nonetheless, the PCM, which emerged out of the French Communist Party and leftist groups in Morocco, was “the primary avenue for Moroccan Jewish expressions of patriotism and participation in the national liberation movement.” Its universalist, expansive definition of “Moroccan” identity appealed to Jews at a time when the majority of national liberation parties, like the Istiqlal, promoted an Arab Muslim national agenda.

“Moroccan Jewish Communists were mostly active in French, but ardently supported Arabization and efforts to bring Moroccan Jews closer to Moroccan Muslims in language, cultural practices and political aspirations,” she says.

Several interlocking forces drew Jews to communism in the first place — the rise of fascism and Nazism, antisemitism, and Arab nationalism.

French Vichy rule in Morocco, with its profusion of antisemitic edicts, led some Moroccan Jews to distance themselves from France. Jewish rights were restored after Operation Torch, the U.S. and British landings in Morocco in November 1942.

After World War II, Zionism achieved popularity in Morocco, being regarded as a cultural expression of Jewish pride and international Jewish identification. Some traditional Jews, as well as the French colonial administration, disapproved of Zionism, perceiving it as a disruptive force in Moroccan society.

Among Moroccan Muslims, rising strife in Palestine prompted them to conflate local Jews with Zionism, a spurious perception that further entrenched the widespread belief that Jews were not real Moroccans.

Jewish Communists had no problem rejecting Zionism. Their position was “one critical means of expressing devotion to the Moroccan state.” As El Maleh wrote in 1949, “We are Moroccans, we are not ‘foreigners,’ as the Zionists would have us believe … We are deeply Moroccan.”

Communists like him encouraged Jews to become more involved in the national liberation movement. But for most Jews, the fierce anti-Zionist atmosphere that enveloped Morocco was problematic, to say the least.

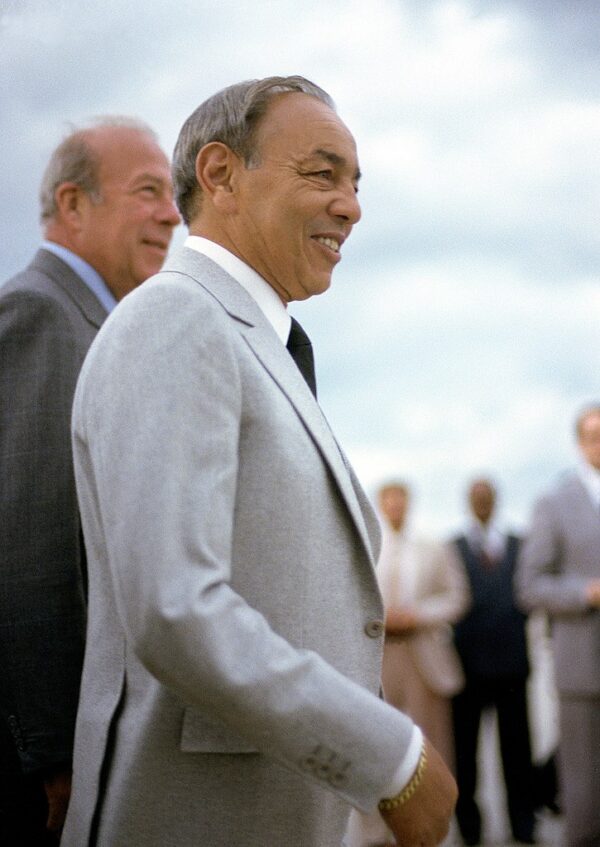

A few months before Israel’s proclamation of statehood, the Istiqlal claimed that all Jews were Zionists and exhorted Muslims to boycott Jewish shops and commercial enterprises. Following Israel’s creation, Sultan Mohammad V denounced Zionism, but urged Jews “not to lose sight of the fact they are Moroccans” and warned them to “abstain from any act that might support the Zionist aggression …”

In 1955, the sultan assured a Jewish delegation that Jews are “citizens with full rights like their Muslim compatriots.” He then appointed his Jewish personal physician, Dr. Leon Benzaquen, a member of Istiqlal, as a minister in the new government.

A year later, after the outbreak of the Sinai war, the sultan told Jewish dignitaries that Jews should remain in Morocco “because their place is here.”

By then, Jews were leaving Morocco in droves. Under popular pressure, the sultan banned Jewish emigration, only to lift the ban months later, enabling an additional 92,000 Jews to leave between 1961 and 1964. With the death of the sultan, Crown Prince Moulay Hassan, his son and the future King Hassan II, ascended to the Moroccan throne. Uncertain of what lay ahead, still more Jews departed.

In the meantime, the PCM denounced antisemitism as antithetical to Moroccan “tradition,” called for greater monitoring of “notorious Zionist agents” who were “denationalizing” Jews, and asked Jews and Muslims to reject the polarizing effects of Zionism.

Amid the tensions, the Istiqlal began publishing openly antisemitic tracts. And one of its former leaders, Allal al-Fassi, said condescendingly that Jews “are nothing but dhimmis,” a derogatory word for tolerated minorities in Muslim societies.

In the aftermath of the Six Day War, Jewish businesses were boycotted. King Hassan II, the self-styled “protector” of Jews, defended the Jewish community and urged Moroccans to distinguish between Jews and Zionists. But he warned Moroccan Jews that their rights as citizens could be compromised by their endorsement of Zionism.

Jewish Communists issued a public declaration calling on Jews to cease their Zionist activities.

Morocco spent a small expeditionary force to Syria during the Yom Kippur War, but the king assured the Jewish community that its security would not be jeopardized.

Upon the Hassan’s death in 1999, his successor, King Mohammad VI, sought to portray Morocco as a beacon of tolerance and pluralism. Jewish Communists, who always had remained loyal to the monarchy, were only too glad to be coopted into the government’s public relations campaign.

“They, too, would become the ‘Sultan’s Communists,'” says Heckman. “They became the very international face of Moroccan openness … while simultaneously being shunned by the majority Jewish community.”