Trust is the fuel we run on and the air we breathe, Barry Avrich muses at the start of his fascinating documentary, The Talented Mr. Rosenberg. Yet, as he quickly adds, trust can be misused as a weapon by the unscrupulous.

Avrich, a prolific Canadian filmmaker, was thinking of Albert Allan Rosenberg, a notorious resident of Toronto, when he made these apt comments.

Variously described as a financial parasite and a psychopath incapable of living within the norms of society, Rosenberg is a convicted fraudster who has bilked clients of their savings and destroyed their lives.

Call him, if you will, the Bernard Madoff of Canada.

A swindler who has perfected the art of the con, he has masqueraded over the years as a member of the Swiss nobility, a lawyer, a doctor and a movie producer. In fact, as Avrich strongly suggests, he is nothing more than a seasoned liar and a cheat of monumental proportions.

As Avrich further says in his film — which is currently making the rounds of international film festivals and is presently streaming on CBC Gem in Canada — Rosenberg is a smart, cunning, and charming operator who has squandered his obvious talents in the pursuit of greed and power and who has been in and out of prisons since the 1980s.

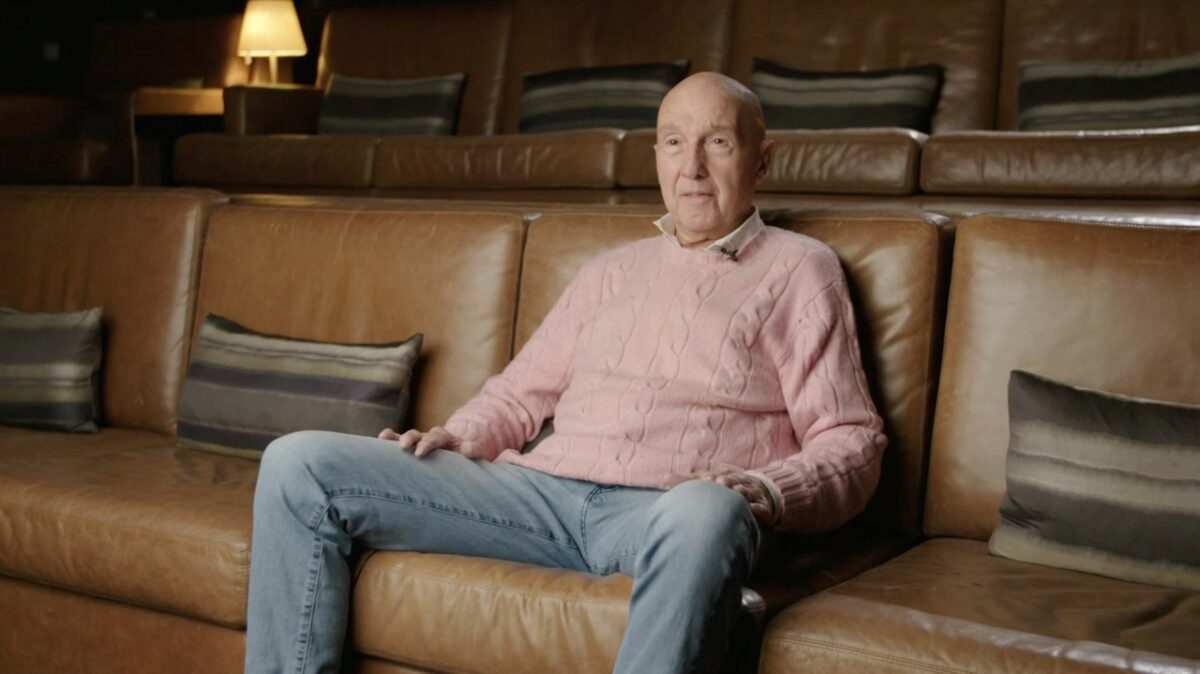

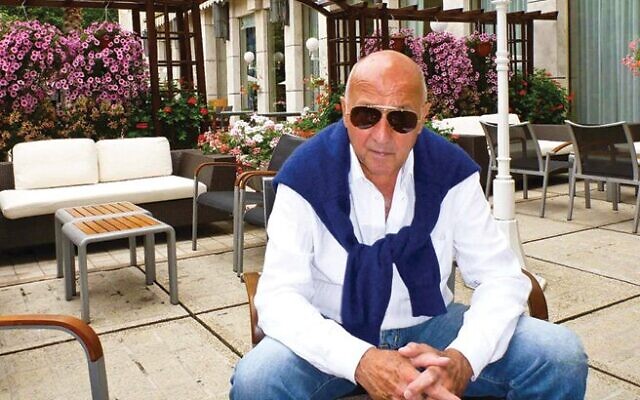

Thieves like Rosenberg normally stay clear of the media. Avrich persuaded him to submit to interviews because Rosenberg wanted to relay a message. “I’m not that bad,” claims Rosenberg, a bald, lanky man dressed in blue jeans and a pink sweater. “I did commit these crimes, but not to the extent they’re saying.”

Rosenberg’s scams were exposed in a Toronto Life article in 2015 by Courtney Shea. One of the film’s writers and producers, she dubbed him the Yorkville Swindler, a reference to the upscale neighborhood in dowtown Toronto in which he lives.

“It hurts to be called the Yorkville swindler,” says Rosenberg, who thinks the magazine was unfair to liken him to some kind of a devil. But as Shea counters, he would rather be known by that moniker than as a nobody.

Rosenberg’s fraudulent schemes have fooled even the high and mighty. Several years ago, one of Canada’s five major banks was on the cusp of investing $20 million in Marwa Holdings, a company owned by Rosenberg that promised investors unheard profits of 20 percent to 30 percent a month.

“He’s remarkably dangerous,” says Diana Henriques, an American journalist who wrote a book about Madoff.

Given Rosenberg’s slippery personality, it is difficult to separate truths from lies in his biography. But as far as Avrich is aware, he was born in Cairo in 1942 and was raised in Switzerland. His mother, Marcelle, was an academic, a fine, upstanding woman, in Rosenberg’s estimation. His father, Salman, was cold and distant and beat him.

After the couple divorced, Rosenberg and his remarried mother moved to Toronto, where she operated a successful boutique in Yorkville. According to Rosenberg, he attended Forest Hill Collegiate and placed third in the province of Ontario in his final year.

He supposedly graduated from the University of Toronto and Harvard University, but neither institution has a record of his enrollment. Rosenberg insists he has diplomas from both universities, but one of his three daughters, who prefers to remain anonymous, challenges this claim. Indeed, she denigrates him as “a very heinous human being.”

He admits he has been “obsessed with money” for years now. One can assume he is telling the truth. But every other facet of his dubious career rests on shifting sands.

In the wake of his first marriage, which was of brief duration, he went to Israel to observe its society and learn Hebrew. Around this period, he met his second wife, Karin, the heir to the Ovaltine fortune in Switzerland and the mother of his children.

Rosenberg’s daughter reveals he was a big spender with very expensive tastes who shrouded himself in secrecy. He was also a spousal abuser, she adds.

The RCMP charged Rosenberg with fraud in a Toronto art gallery scandal. Sentenced to four years in prison, he was released midway through his term. Recalling his imprisonment, he says, “It was devastating.”

During this interregnum, his wife divorced him.

In the 1990s, he fell afoul of the law again after being charged with fraud. He spent the next three years in jail.

He met his third wife, a psychologist, online. “He was very charming and romantic,” she remembers. “He made everything so special.”

He promised to set up a $14 million trust find for her, but instead squeezed money out of her and isolated her from family and friends. In desperation, she contacted the police. Charged with fraud, he was sent back to prison for 18 months.

“Jail time was the cost of doing business,” says a former Toronto policeman sardonically.

At this point in the film, Rosenberg sounds somewhat contrite.

“I wish I could start all over again,” he murmurs, disclosing he has put his criminal past behind him and is devoting himself to charitable works.

In the meantime, he has adopted two new aliases: Allan Rothschild and Allan Rose Wander. One wonders what is going on.

When Avrich asks him to describe his legacy, he pauses before replying: “A good businessman …. and a good father. That’s it.”

In light of Rosenberg’s past, his description of himself is remarkably cosmetic and self-serving.