Fredericka Mandelbaum was no ordinary immigrant.

A German Jew, she arrived in New York City in a near penniless state in 1850. Within a few years, she had created one of the first organized crime rings in the United States.

One of the most infamous underworld figures in the last half of the 19th century, she employed a cadre of bank robbers, housebreakers and shoplifters in a criminal network that specialized in stolen luxury goods and the robbery of banks and stores.

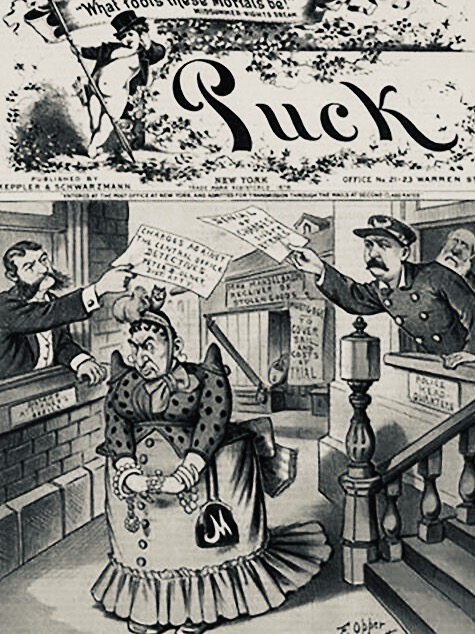

A storied figure whose net worth would be almost $300 million today, she was the subject of news stories, editorial cartoons and a theater play during America’s Gilded Age. She was also mentioned in a spate of books.

She kept no written records herself, realizing they could incriminate her.

Margalit Fox, a New York journalist, has written an engaging biography of this notorious “fence,” or receiver and dispenser of stolen merchandise. The Talented Mrs. Mandelbaum: The Rise and Fall of an American Organized Crime Boss (Random House) takes a reader from her birth in Kassel to her final years in Hamilton, a town in the Canadian province of Ontario.

Early on in the book, she places Mandelbaum in the context of her times: “She was among the first — quite possibly the very first — to systematize the formerly scattershot enterprise of property crime, working our logistics, organizing chains of supply and demand, and constructing the entire venture first and foremost as a business. And in doing so, she simultaneously embodied and upended the cherished rags-to-riches narrative of Victorian America, starring, on entirely her own terms, in a Horatio Alger story of a very different kind.”

Born 1825, she was the daughter of Samuel Abraham Weisner, an itinerant peddler, and his wife, Rahel Lea Solling. Hardship drove the family to emigrate. They arrived in Manhattan, then a largely pastoral island, with practically nothing.

Marm, as she was known, was already married when she set foot in America. Two years earlier, she had wed Wolf Mandelbaum. He died in 1875 at the age of 51, leaving her as the sole supporter of their four children.

They lived in a shabby tenement in the Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) quarter of the Lower East Side, which would become a refuge for European Jewish immigrants. It would be Mandelbaum’s neighborhood for the rest of her life.

A hulk of a woman, six feet tall and weighing between 250 to 300 pounds, she started as a door-to-door peddler of lace. She soon became a protege of Abe Greenthal, a master fence and one of the “shrewdest criminals in this country,” as The New York Times noted.

Under the tutelage of Greenthal and his associates, she became an expert in appraising the value of textiles and luxury goods that passed through their hands fleetingly. “The skills she acquired laid the foundation for her criminal career,” writes Fox, a fluid writer who brings Mandelbaum’s almost forgotten story to life.

Mandelbaum worked out of a street level shop and basement at 163 Rivington Street, which served as her headquarters for two decades. It was there that she became the most celebrated “fence” in American history.

“She made her underworld ascent in a congenial climate of mass production, middle class desire, rampant graft and endemic police corruption,” writes Fox.

Mandelbaum’s army of thieves robbed high-end stores, textile houses and the homes of the wealthy. She played an active role in planning these crimes and underwriting their expenses.

Unlike most criminals, she played fair with her associates. “She attained a reputation as a business woman whose honesty in criminal matters was absolute,” said the city’s police chief, George Washington Walling.

With so much merchandise at her disposal, she distributed her goods to warehouses throughout the city and in neighboring New Jersey and to rental rooms in a string of local apartment buildings. As Fox says, she took great care not to have them sent directly to her shop.

She was at the height of her career from the late 1860s to the mid-1870s, during an era characterized by “rapacious greed, unregulated speculation, rampant corruption and a widening chasm of income inequality.”

This accounts for the fact that she barely spent time behind bars. Mandelbaum mingled with the rich and famous and used her connections to avoid prison.

She projected an image of herself as an upstanding member of the Jewish community and an attentive mother. “Her neighbors adored her,” writes Fox. “As someone who created jobs, offered discounts and dispensed charity when needed, she was seen as a local benefactor.”

Even Walling had something good to say about his adversary, calling Mandelbaum “a woman and a mother spoken of with respect.”

Inevitably, the police caught up with her, forcing Mandelbaum to flee to Canada. Fortune there did not smile on her. In Hamilton, she and an associate were found with a suspicious package of precious jewels and stones worth upwards of $40,000. The goods were impounded by Canadian Customs for non-payment of duty.

Nonetheless, Mandelbaum continued to ply her trade in Hamilton until the early 1890s. During her final years, she was afflicted with painful illnesses. She died on February 26, 1894 at the age of 68, and was buried in a cemetery in New York City’s Queens borough.

Fox ends on a somewhat mischievous note: “At the internment, it was reported afterward, some mourners deftly picked the pockets of others. Whether they did so in tribute to their fallen leader or simply from occupational reflex is unrecorded.”