Thousands of books have been published about World War II, but Lizzie Collingham’s book, The Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food (Penguin), is unique. As far as I know, it’s the first that examines the role food played in that protracted conflict. Collingham’s topic, often overlooked by historians, is extremely important, since starvation and malnutrition killed more civilians than soldiers.

Food, as she correctly points out in this meticulously researched and illuminating volume, was a driving force in Germany’s decision to invade the Soviet Union and murder Jews on an industrial scale during the Holocaust.

And food, she adds, gave the United States a distinct advantage over its enemies.

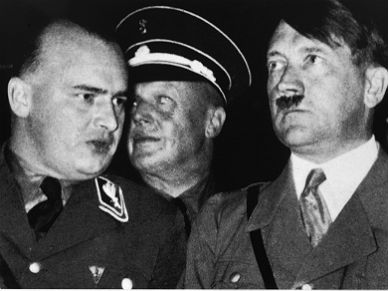

No less a person than Adolf Hitler drew a relationship between the supply of food and military strategy. In May1942, in a secret speech to young army officers, he said, “It is a battle for food, a battle for the basis of life, for the raw materials the earth offers, the natural resources that lie under the soil …”

Hitler, of course, was talking about Lebenstraum, the concept that required Germany to expand eastwards to achieve self-sufficiency in food production. The Reich Food Corporation, an arm of the German government, calculated that Germany needed another seven to eight million hectares of farmland in order to feed its population. This meant that Poland and the Soviet Union would have to be conquered. Germany had a variety of reasons for attacking Poland and the Soviet Union, but food was certainly one of them.

As Collingham writes, “The Third Reich viewed the whole of occupied Europe, not just the Soviet Union, as a source of food for the Germans.” Just as Britain depended on its allies and overseas colonial empire for food imports, Germany regarded the occupied territories as a vital source of food, she says.

Germany introduced rationing on the home front in August 1939, before its invasion of Poland. While German citizens were entitled to a decent ration, the non-productive and racially undesirable, namely Jews, were not accorded the same privileges. The mentally ill and disabled were restricted to a diet devoid of fats and very low in protein, while Jews were allowed to shop only at designated shops, which often charged them at extra 10 percent.

By the summer of 1941, supply problems led to food shortages in Germany. For two weeks in November of that year, for example, it became impossible to buy potatoes, sparking protests in the city of Cologne. As the war dragged on and food supplies dwindled, Horcher’s, the finest restaurant in Berlin and a haunt of the Nazi elite, closed its doors.

The greatest difficulty faced by German farmers was a shortage of labor, but Germany solved the problem by importing millions of Polish and Ukrainian forced laborers as well as Soviet prisoners of war.

The German army was a voracious consumer of food, swallowing 40 percent of the grain and 62 percent of the meat available to Germany, but on the whole, as Collingham points out, the Soviet Union was the main food supplier for the Wehrmacht.

Countries under Nazi occupation, like Denmark and France, were a critical source of meat. In some captive nations, such as Greece, Germany plundered food supplies, to the detriment of the civilian population.

Food shortages in Poland and the Soviet Union emboldened the Nazis to accelerate the slaughter of Jews. Hans Frank, the German governor general of occupied Poland, informed Hitler in December 1941 that plans to deport Polish Jews to the east were no longer viable. Since Jews were “extremely damaging eaters,” they had to be removed as quickly as possible, he said.

A month later, at the infamous Wannsee conference in Berlin, Germany decided to exterminate the Jews of Europe on a systematic basis.

“The Jews could not be allowed to continue eating the precious food which (Germans) deserved,” Collingham writes. “They must die in order to free up desperately needed food supplies.”

The same ruthlessness was applied to captured Soviet troops. By her estimate, 500,000 to 700,000 Red Army soldiers were starved to death between October 1941 and March 1942. The German siege of Leningrad, which prompted some of its inhabitants to resort to cannibalism, became an iconic symbol of starvation during the war.

The average Soviet citizen, who consumed at least 500 calories less than the average British or German civilian, survived on far less food than all other combatant nations except the Japanese. But Soviet leaders had no such problems. “At Kremlin banquets, caviar, fish and meat were all washed down with liberal quantities of vodka, wine and cognac,” she notes. “It was a bitter reality that during these years of terrible privation the communist elite was cushioned from the suffering, just as they had always been.”

Acting on the principle of self-sufficiency, the Red Army, in 1943, established 5,000 farms to produce meat, milk, eggs, potatoes, green vegetables, mushrooms and fish. “By 1944, these were able to cover a good proportion of the protein requirements of the standard military ration,” she says, adding that in the final two years of the war Red Army soldiers were finally guaranteed a ration that contained more calories and a better quality of food than the civilian ration.

The issue of food supply was crucial in Japan, too.

As Collingham puts it, “Military and right-wing groups used the need to secure the urban food supply and crisis in the Japanese countryside to justify ever more radical actions, beginning with the seizure of Manchuria in 1931 and culminating in the war against Nationalist China in 1937. Finally, the Japanese determination to hold China in the face of American disapproval set them upon a collision course with the United States.”

Prior to the war, she observes, most of the Japanese army recruits drawn from the countryside had been malnourished and physically weak. A military committee, having concluded that the customary Japanese diet of rice, miso soup and a little fish and vegetables would not produce battlefield warriors, recommended an increase in the amount of meat in the ration. The recommendation was accepted, but in practice, it was not always followed.

Surprisingly enough, Japan’s military leadership exhibited a cavalier attitude toward food supplies for troops in the field. As a result, 60 percent of Japan’s 1.7 million casualties were due to starvation, not combat.

In general, Japan’s dependence on food imports, blocked by a U.S. blockade enforced by submarines, aircraft and mines, led to a steadily worsening food crisis in 1944 and 1945. Civilians had access to noodles only once a week, meat virtually disappeared off the shelves, fish was hard to come by and expensive and milk was available only for the sick and children.

From the outset, the United States understood that modern war demands enormous stocks of food, not only for soldiers and sailors, but for workers employed in war-related industries. Consequently, American soldiers were the best fed.

“The superior rations which U.S. troops — and ordinary civilians — received thus became a powerful signifier of American strength and superiority, not only for the Americans themselves but also for their allies and enemies,” she says.

Although the United States introduced meat rationing in 1943, it continued to send its beleaguered ally, Britain, hundreds of tons of meat, thereby stabilizing its food supply, which remained stable and adequate throughout the war.

Canada, famous for its golden wheat fields, was also a supplier, replacing Denmark as Britain’s chief source of bacon. Indeed, the war brought Canada’s farming sector out of depression and solved the problem of rural unemployment by siphoning surplus labor into industry.

In The Taste of War, Collingham gives a reader new and valuable insights into an intriguing facet of warfare. As she suggests, an army fights on its stomach.