They were burdened with the most gut-wrenching, repulsive job a Jewish inmate in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland could possibly be assigned.

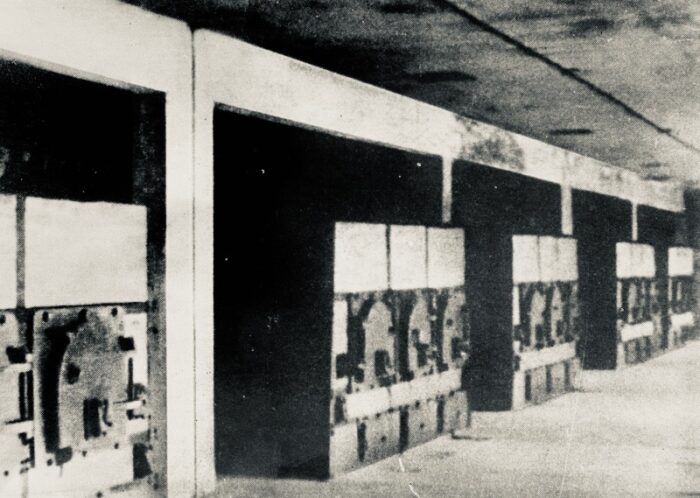

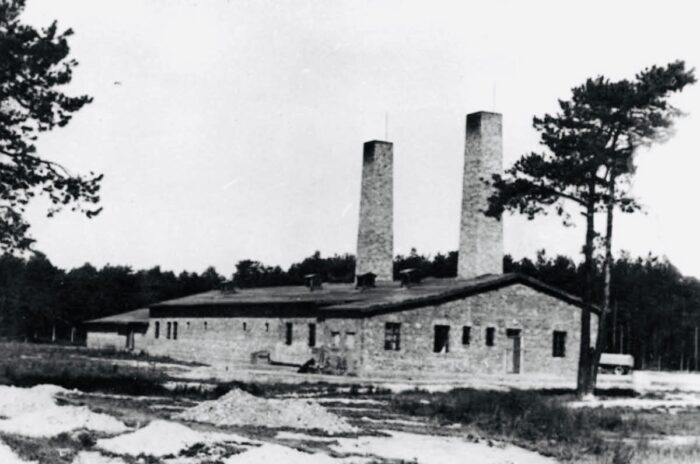

Their gruesome task was to escort Jewish deportees into the gas chambers, remove their lifeless bodies, salvage valuables, transport the corpses to the crematoria, and destroy all evidence of their murders.

Known in German as sonderkommandos, they were forcibly recruited by the SS to carry out these unbearable and dehumanizing tasks. The strongest ones somehow accustomed themselves to this horrific work. The weakest ones eventually committed suicide. Many of the others were murdered by their Nazi masters to eliminate witnesses to the greatest genocidal crime of the 20th century.

As if to atone for their forced participation in the Holocaust, several hundred sonderkommandos took part in a revolt on October 7, 1944. Zalmen Gradowski, a Polish Jew, was one of the leaders of the failed uprising.

Gradowski, who perished during this short-lived rebellion, expressed his rage and contempt toward the Nazis by keeping a secret journal. Written in Yiddish in the autumn of 1943, it was dedicated to his family, all of whom were murdered upon their arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“My aim in writing is that at least a tiny part of this reality should reach the world and that you, world, will then take revenge, revenge for everything,” he wrote.

The manuscript in which these words were written was found near a crematorium by a Soviet-Polish commission on March 5, 1945, slightly more than a month before Germany’s unconditional surrender and the end of hostilities in Europe.

Gradowski’s journal, a poignant testimony of grief and anger, has been published by the University of Chicago Press under the title of The Last Consolation Vanished. Edited by Arnold Davidson and Philippe Mansard, who provide a foreword, it was translated into English by Rubye Monet.

Gradowski, born between 1908 and 1910 in Suwalki, a village near Lithuania, came from a family of very religious shopkeepers. A fervent Zionist, he was an active member of the right-wing Betar movement, which was founded by Vladimir Jabotinsky. When German forces occupied Suwalki in 1941, he and his wife, Sonja, settled in a village in the province of Bialystok.

On December 8, 1942, he and his family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On the same day, as his wife and children were killed, he was assigned to a sonderkommando unit in crematorium III. He was one of 2,200 prisoners conscripted into the sonderkommando in this concentration camp.

“Day after day, they participated in the destruction of their own people, while unable to reveal the truth to them,” write Davidson and Mansard. “They also facilitated the murder of prisoners deemed no longer capable of work during selections.”

In exchange, they benefited from better treatment at the hands of their Nazi overlords. They were fed, clothed and given a bed. Nevertheless, they lived in “extreme distress.”

Unable to live with themselves, several hundred sonderkommandos revolted. “The SS reaction was immediate. Over the next few hours, more than 400 members of the sonderkommando were killed. The extermination of the Jewish convoys continued at least until the first few days of November, when the surviving members of the sonderkommando were tasked with dismantling the machinery of extermination and erasing all traces of the crimes committed there.”

Between 1945 and 1980, the buried manuscripts of five members of the sonderkommandos were discovered on the grounds of Auschwitz-Birkenau. All of them were published. Gradowski’s was the longest of these heartfelt testimonies.

Until recently, as the editors point out, the history of the sonderkommandos was neglected. The reason is clear. They were considered pariahs, even traitors, although it was understood that they were forced into their positions on pain of death.

Surprisingly enough, the sonderkommandos have been at the center of two movies. The first, The Grey Zone, was directed by Tim Blake Nelson and came out in 2001. The second, Son of Saul, was directed by Laszlo Nemes and was released in 2015.

Gradowski’s journal, which fills much of The Last Consolation Vanished, was forged on the anvil of ceaseless agony. As he tells readers, “You will not believe that such horrendous destruction could be the work of people, even if those people had been turned into animals.”

He deals poignantly with a wide range of topics.

“You ask why Jews did not mount a resistance,” he writes in connection with the failure of most Jews to resist Nazi violence. “Because they had no trust in their neighbors, who would have betrayed them at the slightest setback. They could count on no elements who would seriously help …”

Gradowski expresses astonishment that the Holocaust happened. “Who would believe that they (the Nazis and their collaborators) would lead an entire people to destruction? Who would believe that a highly civilized people would turn into devils whose only ideal is murder?”

He sympathizes with the plight of the doomed Jewish children. “They can’t understand what people want from them … They cry and their mothers cry too over their bitter fate …”

Placing himself in the shoes of new arrivals, he writes, “See who has come to welcome us. Soldiers with helmets, rifles in their arms, accompanied by big fierce dogs. Are these the open arms that have come to greets us? No one understands why there is such a guard. Why such a terrifying welcome? For what?”

In a reference to the false and naive perception that Auschwitz-Birkenau was a merely resettlement camp, Gradowski writes,”Haven’t we come to work as calm and peaceful people. Then why all the security measures?”

Gradowski, in a few brushstrokes, captures the visceral fear of the deportees after they have disembarked from the cattle cars: “The unfortunate victims have arrived. Their hearts are frozen. They stand in helpless terror, resigned and dejected … They cannot understand what they (the Nazis) want from them … They sense that all, this life, is vanishing.”

He empathizes with the deportees as he leads them to their deaths. “We suffer and bleed along with them and feel that each step we take is a step further from life, a step closer to death.”

Having guided them into a gas chamber, he feels guilt. “They know that this is not a bath, but a corridor that leads to the grave … We see before us bubbling, quivering, passionate lives, all in full bloom …”

The rest of his journal unfolds in similar fashion. Here was a sensitive soul who, through no fault of his own, was complicit in the mass murder of his people.

Jews like Gradowski were wretched and tragic figures who were despised and demonized by their fellow Jews. They were the misbegotten spawn of the genocidal Nazi regime.

This is what emerges from The Last Consolation Vanished, a book that melts your heart.