Two Palestinian uprisings in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip have broken out in the past 36 years, the first in 1987 and the second in 2000. A third intifada is looming in light of a significant upsurge of Palestinian violence, Israeli retaliatory raids, and the absence of any movement toward resolving the century-old Israeli-Palestinian dispute by diplomatic means.

Last November, the United Nations issued a warning that Israel’s perennial conflict with the Palestinians was yet again reaching “a boiling point.”

Seventeen Israelis and two foreign workers were killed in terrorist incidents inside Israel last year, the highest toll in years. Starting last spring, Israel launched a series of reprisal raids in and around the northern West Bank town of Jenin, the home of two of the Palestinian assailants.

These attacks, plus additional skirmishes between Israel and Palestinian gunmen, resulted in more than 2,500 arrests and the deaths of some 170 Palestinians, almost double the figure for 2021.

On January 27, a lone Palestinian terrorist bent on exacting revenge killed seven Israelis as they left a synagogue in Neve Yaakov, an Israeli settlement near the center of Jerusalem. Shortly afterwards, Israeli commandos raided a Palestinian refugee camp in Jenin, killing 10 Palestinians. This raid angered the Palestinian Authority, prompting it to announce the severance of security coordination relations with Israel for the third time in six years.

On February 6, Israeli troops clashed with a band of Palestinians near the West Bank town of Jericho. They were reportedly on the verge of attacking a nearby Jewish settlement. The five Palestinians who were killed were members of Hamas’ armed wing. With their deaths, the number of Palestinians killed in clashes with Israeli forces so far this year rose to 40.

Hamas, an Islamic organization dedicated to Israel’s destruction, rules the Gaza Strip, from which Israel withdraw unilaterally in 2005. Since 2008, Israel and Hamas have fought four cross-border wars.

The spike in fatalities prompted the director of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, William Burns, to voice concern that a new intifada may be in the works. Burns, who spent several days in Israel and the West Bank last week, told the Georgetown School of Foreign Service in Washington, D.C. a few days ago that he detected signs of trouble.

“I was a senior U.S. diplomat 20 years ago during the second intifada, and I’m concerned, as are my colleagues in the intelligence community, that a lot of what we’re seeing today has a very unhappy resemblance to some of those realities that we saw then too,” he said.

“The conversations I’ve had with Israeli and Palestinian leaders left me quite concerned about the prospects for greater fragility and even greater violence between Israelis and Palestinians,” he added.

Since Burns is a highly informed observer, his appraisal of the facts on the ground should be taken with the utmost seriousness.

The current tensions are rooted in several factors.

The Palestinians are extremely angry and frustrated by the glaring absence of a credible political process that could lead to a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, a body created by the 1993 Oslo peace negotiations.

Oslo was a historic breakthrough in terms of atmosphere and optics, but it did not give the Palestinians statehood, but only autonomy in Area A of the West Bank.

A wave of Palestinian terrorism, perpetrated in the main by Hamas, caused the deaths of hundreds of Israelis from 1994 to 1999 and enabled the Likud Party to win the 1996 general election. This bloodshed disillusioned many Israelis about the prospect of peace with the Palestinians.

Negotiations under the sponsorship of the United States resumed in the summer of 2013, but collapsed in the spring of 2014 without any meaningful results. During this period, the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, never even met to discuss the issues at hand. The pair conferred last in 2010, though they have greeted each other at various events since then.

From 2015 until his ouster from office in 2021, Netanyahu failed to engage the Palestinians in peace talks, claiming that Abbas and his colleagues were neither reliable nor trustworthy partners. The Palestinians levelled the same accusation against Netanyahu and his ministers.

In the meantime, Israel consolidated its chain of settlements and reinforced its occupation of the West Bank, much to the chagrin of the Palestinians.

Netanyahu’s right-wing and centrist successors, Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid, did not enter into talks with the Palestinians either, though they eased the occupation with economic incentives.

The leadership of the Palestinian Authority repeatedly called for a “political horizon,” or direct peace talks that could lead the Palestinians closer to statehood, but these calls were ignored by Israel.

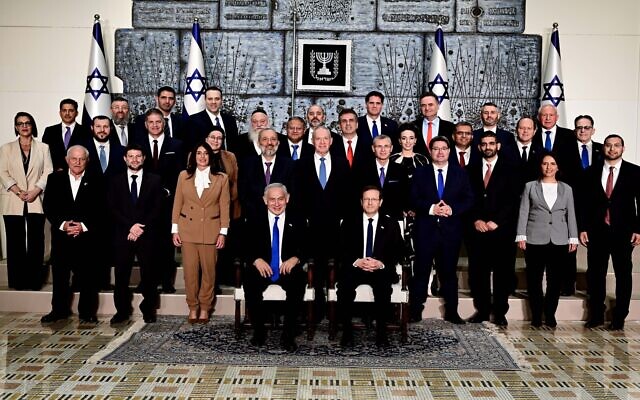

The establishment of a new Israeli government late last year under Netanyahu’s premiership has pushed the issue of Palestinian statehood completely off the table. For several years after his reelection in 2009, under intense pressure from the United States, he paid lip service to a two-state solution, but abandoned this position after the end of peace talks in 2014.

The government he leads today, the most right-wing in Israeli history, is largely composed of zealots like Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich who want to expand the settlements, annex vast swaths of the West Bank, deepen the occupation, and deny the Palestinians the right to independence and sovereignty.

In one of its first measures, Netanyahu’s government halted the flow of taxation funds to the Palestinian Authority after it formally asked the International Court of Justice in The Hague to investigate Israel’s occupation of the West Bank.

In recent discussions with U.S. President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, Abbas bitterly complained about Israel’s “unilateral moves” in the West Bank. He defined these as settlement expansion, the establishment of unauthorized outposts, land expropriations, home demolitions, the absence of freedom of movement, Jewish settler violence, and Israeli army incursions into Area A, which the Palestinian Authority fully administers under the 1995 Oslo accord.

Although the Palestinian Authority is the internationally recognized representative of the Palestinian people, many Palestinians have lost faith in it, regarding it as autocratic, corrupt and incapable of achieving statehood. Most Palestinians oppose security cooperation with Israel, regarding it as a sellout to Palestinian national interests.

Due to all these factors, some Palestinians have called for a third intifada to break the political logjam.

The first Palestinian uprising erupted in the Gaza Strip in December 1987 and quickly spread to the West Bank, resulting in the deaths of 185 Israelis and about 1,000 Palestinians. The rebellion petered out in 1993 as the Oslo peace process got under way.

The second intifada started in September 2000 and lasted until Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza five years later. Far bloodier than the first one, it cost the lives of more than 1,000 Israelis in suicide bombings, shootings and knife attacks and of a little more than 3,000 Palestinians.

What these uprisings had in common was that both ended only after significant Israeli territorial and political concessions to the Palestinians.

Given his hardline views and the composition of his staunchly conservative government, Netanyahu has no intention of offering the Palestinian Authority anything of real political value. Which is precisely why grassroots Palestinians may lose all hope and resort to a systematic campaign of violence to achieve strategic objectives that are now unattainable. Hamas has been encouraging armed resistance, but the Palestinian Authority is officially against it.

The Palestinians would stand little chance militarily against the Israelis, but they could inflict painful casualties on Israel and further tarnish its already battered international image.

The West Bank is a ticking time bomb. Whether it explodes into all-out violence has yet to be seen. But all the signs of a massive explosion are in place.