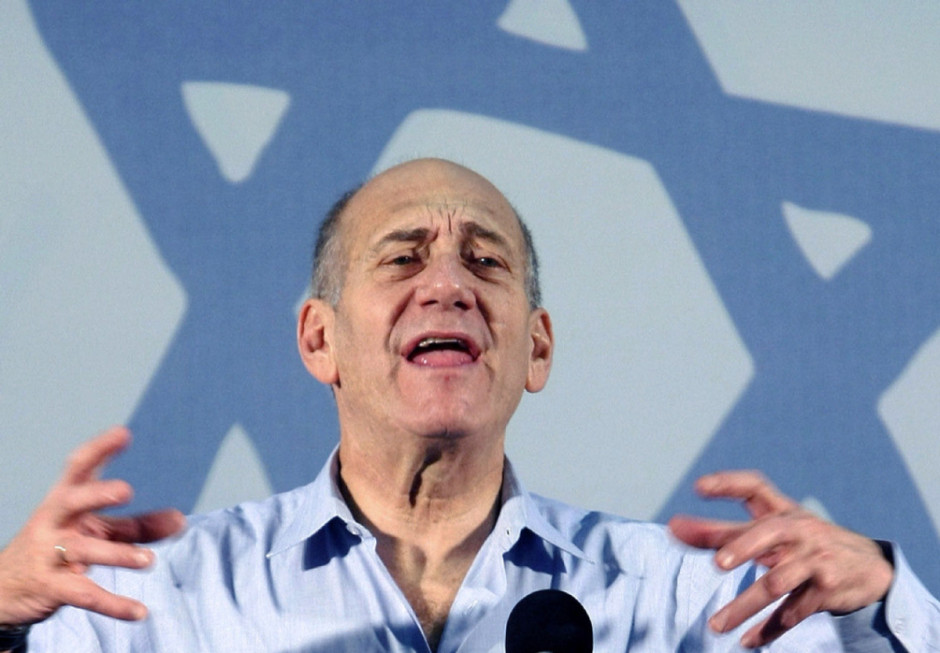

Standing on the cusp of becoming Israel’s first former prime minister to be packed off to jail and stamped with the infamy of a criminal record, Ehud Olmert is making history for entirely the wrong reason.

On May 25, a district court in Jerusalem sentenced him to eight months imprisonment on charges of breach of trust and fraud. The case turns on illegal transfers of money between the early 1990s and 2005, when he was mayor of Jerusalem and minister of industry of trade.

If his appeal fails, Olmert — who’s currently challenging a six-year sentence for taking brides in another case — will have to grin and bear it and present himself to prison authorities in July.

What a waste. What a tragedy.

Olmert succeeded Ariel Sharon as prime minister in 2006 and resigned some three years later, squandering a golden opportunity to become a reasonably successful and acclaimed leader.

Starting his political career as a hawk, he evolved into something of a dove, realizing that Israel’s future as a democratic Jewish state would be compromised by its continual occupation of Arab lands.

As a member of the right-wing Likud Party, Olmert initially opposed Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s courageous and far-sighted decision to relinquish the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for a peace treaty with Egypt. Years later, Olmert recanted, saying he regretted his intransigent stance.

In line with fellow Likudniks, Olmert was also vehemently against an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank. But following his departure from the Likud and his involvement in the centrist Kadima Party, he had a philosophical change of heart.

He became a realist.

As prime minister, he threw himself vigorously into the role of peacemaker, attempting to reach a viable and durable agreement with the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas. The pair conducted face-to-face meetings 36 times, hoping to resolve deep-seated differences over a variety of immensely difficult issues.

By all accounts, Olmert and Abbas came tantalizingly close to sealing a historic accord. Their talks finally came to naught because the stench of corruption had already enveloped Olmert. By that juncture, Abbas was loathe to deal with a lame duck prime minister, though he should have done so.

But say this for Olmert. Unlike his successor, Benjamin Netanyahu, he seems to have been sincerely interested in pursuing a two-state solution, knowing it would save Israel from the trap of a binational solution.

Like his predecessors Yitzhak Rabin and Ehud Barak, Olmert tried to engage Syria — one of Israel’s most implacable enemies — in peace negotiations. Less than a year after he had ordered the bombing of Syria’s North Korean nuclear reactor, Israel and Syria were cast into the cut and thrust of indirect peace talks thanks to the good offices of Turkey, then an Israeli ally.

These negotiations might have borne diplomatic fruit, but they collapsed after the eruption of the Gaza war at the end of 2008. Hamas and its ally, Islamic Jihad, initiated these hostilities by bombarding Israel with rocket and mortar fire. Olmert responded by unleashing Operation Cast Lead, which gave Israel an almost three year reprieve of relative quiet along the Gaza border.

Olmert was not afraid to resort to military means to deter aggression. In the summer of 2006, he went to war with Hezbollah after it had launched a brazen cross-border raid into the Galilee that claimed the lives of several Israeli soldiers. Arguably, he could have been more measured in his response. But the fact of the matter is that the Second Lebanon War, for all its operational failures, restored Israel’s deterrence vis-a-vis Hezbollah, a considerable achievement considering everything.

In retrospect, Olmert was a decisive, tough-minded, flexible prime minister, a man of vision who had the potential to improve Israel’s geopolitical position in the Middle East. Regrettably, his personal flaws undermined the positive legacy he might have bequeathed to his country and his people.