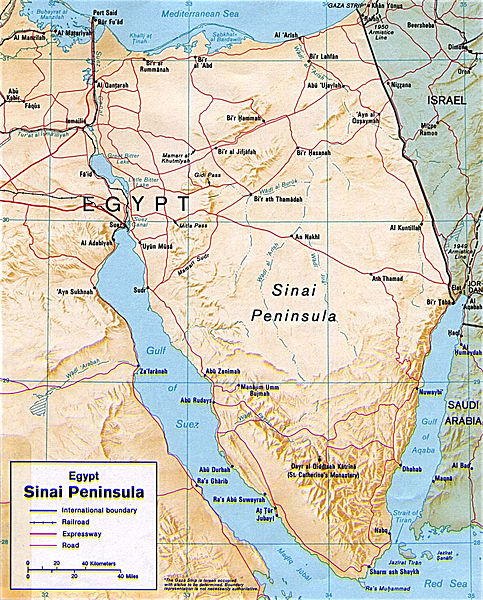

On my last visit to Egypt, in 1999, I spent several days in one of my favorite places, the Sinai Peninsula, a 61,000 square kilometer desert of spectacular Red Sea coast lines, undulating sand dunes, shady oases and craggy mountains.

I was truly in my element as I explored this pristine region, which on a map resembles a triangle.

A hub of the Israeli tourist industry until Israel’s withdrawal in 1982, the Sinai has since become a haven for Islamic fundamentalist terrorists, despite Egypt’s best efforts to dislodge them. In 2004, 2005 and 2006, terrorists carried out deadly attacks in Taba, Sharm-el Sheikh and Dahab, all of which I’ve visited over the course of several trips since 1967. And since 2013, Sinai Province — an affiliate of Islamic State known as Ansar Bayt a-Maddis until last year — has been at war with the Egyptian army in the northern Sinai.

In light of the situation prevailing there today, I would think twice before venturing into Sinai again.

Mohannad Sabry, an Egyptian journalist who has reported extensively from the Sinai despite government press restrictions, has watched its transformation from tourist mecca to terrorist enclave. In his highly informative book, Sinai: Egypt’s Linchpin, Gaza’s Lifeline, Israel’s Nightmare (The American University in Cairo Press), he charts Sinai’s downward spiral in minute detail.

As he points out, Sinai has gone through several distinct phases. Prior to the 1967 Six Day War, Sinai, remote and isolated, was little more than an Egyptian military zone, its Bedouin population marginalized and its economic development stunted.

Israel’s conquest of Sinai was the start of a new era in its history. Israel paved roads and built settlements. Israelis, hungry for wide open spaces, spectacular landscapes and solitude, flocked in droves to its beaches, rudimentary resorts and the St. Catherines monastery, at the foot of iconic Mt. Sinai, even as Israel and Egypt fought the War of Attrition along and around the Suez Canal from 1968 to 1970. Sinai prospered as never before, with the Bedouins reaping unprecedented economic benefits.

Israel, in fulfilling one of the main requirements of its 1979 peace treaty with Egypt, pulled out of Sinai in phased withdrawals. Egypt, having belatedly recognized Sinai’s great tourist potential, built new hotels and expanded existing facilities, as well as developing and offering new Egypt property for sale in many different areas, not just Sinai.

During the 1990s, as Egypt battled an Islamic insurgency in the Nile delta, Muslim radicals from the mainland filtered into the ragged towns and far-flung villages of northern Sinai, as Sabry points out. On October 7, 2004, an outfit known as Kataib al-Tawhid al-Islamyia drove three explosive-laden vehicles into the Hilton Taba Hotel and two beach camps in Nuweiba, killing 34 people, including 12 Israelis.

By all accounts, it was the first terrorist attack in the Sinai.

According to Sabry, the first smuggling tunnels between the Sinai and the Gaza Strip were constructed in 1983, a year after Israel’s pullout. Initially, the tunnels were used to smuggle drugs and Russian/Eastern European prostitutes, but eventually, they were utilized to funnel arms to the Palestinian Authority — which was created by the 1993 Oslo accords — and Hamas.

Iran, Israel’s paramount enemy, exploited the maze of tunnels to smuggle in blueprints and rocket parts for Hamas’s growing stockpile of Qassam and Grad rockets. The downfall of Libya’s dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, also facilitated the flow of weapons, including anti-aircraft missiles, from Sinai to Gaza.

The Israeli and Egyptian blockade of Gaza, instituted following Hamas’ takeover in 2007, increased the importance of the tunnels. “We had to build the tunnels since no electricity, water or food (was) coming in from outside,” Sabry quotes the co-founder of Hamas, Mahmoud al-Zahar, as saying.

The tunnels were privately owned, but Hamas taxed incoming goods, thereby bolstering its coffers. By 2008, the year the first Gaza war broke out, imports flowing into Gaza from Sinai were worth an estimated $650 million. By Sabry’s estimation, the massive profits derived from smuggling strengthened Hamas, invigorated Sinai’s economy and relieved the Egyptian government of its responsibility toward the impoverished population of northern Sinai.

Hundreds of tunnels were damaged and destroyed by Israel in Operation Cast Lead, which unfolded from December 2008 to January 2009, but they were rebuilt. Some were as long as 1,500 meters and two meters wide. By mid-2009, the tunnels could handle more than four times the previous flow, he estimates.

Egypt started raiding the tunnels, blocking them with solid waste, rocks and sand, but their proprietors promptly put them back into operation. Sabry says there were at least 1,200 operating tunnels by the end of 2010.

Islamic militancy gained new ground in northern of Sinai after the collapse in 2011 of Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year authoritarian regime. Sabry believes one of the reasons for his fall may have been the anger that a natural gas agreement between Egypt and Israel had aroused. Under the deal, signed in 2005, gas was shipped through a pipeline from El Arish, the capital of northern Sinai, to the southern Israeli port of Ashkelon. What upset some Egyptians, particularly Islamists and Nasserites, was that the natural gas was sold to Israel at “subsidized” prices. “Israel was buying Egyptian natural gas for prices eight to ten times less than prices paid by other countries to various exporters,” says Sabry.

Not surprisingly, the Islamist movement in Sinai — which allied itself to Al Qaeda before expressing allegiance to Islamic State — called for the application of Sharia law and the revocation of Egypt’s peace treaty with Egypt.

On August 18, 2011, six months after Mubarak’s ouster, Sinai-based Islamic radicals staged their first cross-border attack against Israel, killing six Israeli motorists driving along Highway 12 in the Negev Desert. The incident prompted Israel’s defence minister to call attention to the weakness of Egypt’s hold over the Sinai and broke decades of quiet along Israel’s border with Egypt.

Less than a month after this attack, protesters ripped the flag off the Israeli embassy in Cairo.

Following Israel’s bombardment of Gaza in Operation Pillar of Defence in November 2012, Mohammed Morsi — a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt’s first democratically-elected president — recalled the Egyptian ambassador to Israel and ordered the full opening of the Rafah border terminal.

In the wake of the military coup in July 2013 that toppled Morsi, jihadists in Sinai launched an armed campaign against Egyptian army and police checkpoints, patrols and bases in and around the towns of El Arish, Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayyed. This insurrection, which has claimed the lives of hundreds of Egyptian servicemen, has yet to be quelled.

Egypt’s new strongman, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the former chief of staff of the armed forces, claimed that Hamas and its armed wing, the Qassam Brigades, were involved in these attacks. According to Sabry, Sisi’s antagonism toward Hamas is justifiable. Hamas, he points out, orchestrated major arms trafficking operations after the eruption of the civil war in Libya. Hamas also refused to cooperate with Egyptian authorities in cracking down on jihadists moving freely between Gaza and northern Sinai.

These tactical mistakes were the result of Hamas’ erroneous belief that the Muslim Brotherhood would rule Egypt indefinitely, Sabry observes. “But to accuse (Hamas) of sponsoring terrorists … contradicts the deep-rooted animosity between Hamas and the Salafi jihadist movement in general,” he adds.

Sabry expects Sinai to be a continuing source of problems for Egypt and Israel alike. He is right, of course. Two and a half months ago, Sinai Province took credit for the downing of a Russian charter plane, carrying 224 passengers and crew, over central Sinai.

Clearly, much of Sinai is no longer an idyllic place where tourists may roam in peace and contentment. Its transformation has been one of the most depressing developments in the annals of the region, as Sabry intimates in his fine book.