Twenty years ago, on March 19, the second Gulf War in 12 years erupted as the United States launched devastating “shock and awe” air strikes in Baghdad in a prelude to its massive ground invasion of Iraq a day later.

The American military campaign came on the heels of the Al Qaeda terrorist attacks that brought down the World Trade Center in New York City and impelled the United States to invade Afghanistan and oust its Taliban regime, which had provided a sanctuary to Al Qaeda’s fighters.

A coalition of some 45 nations, ranging from Britain to Poland, joined the United States in its bid to combat terrorism and transform the Middle East.

Two decades on, it is clear that the invasion had profound and lasting consequences.

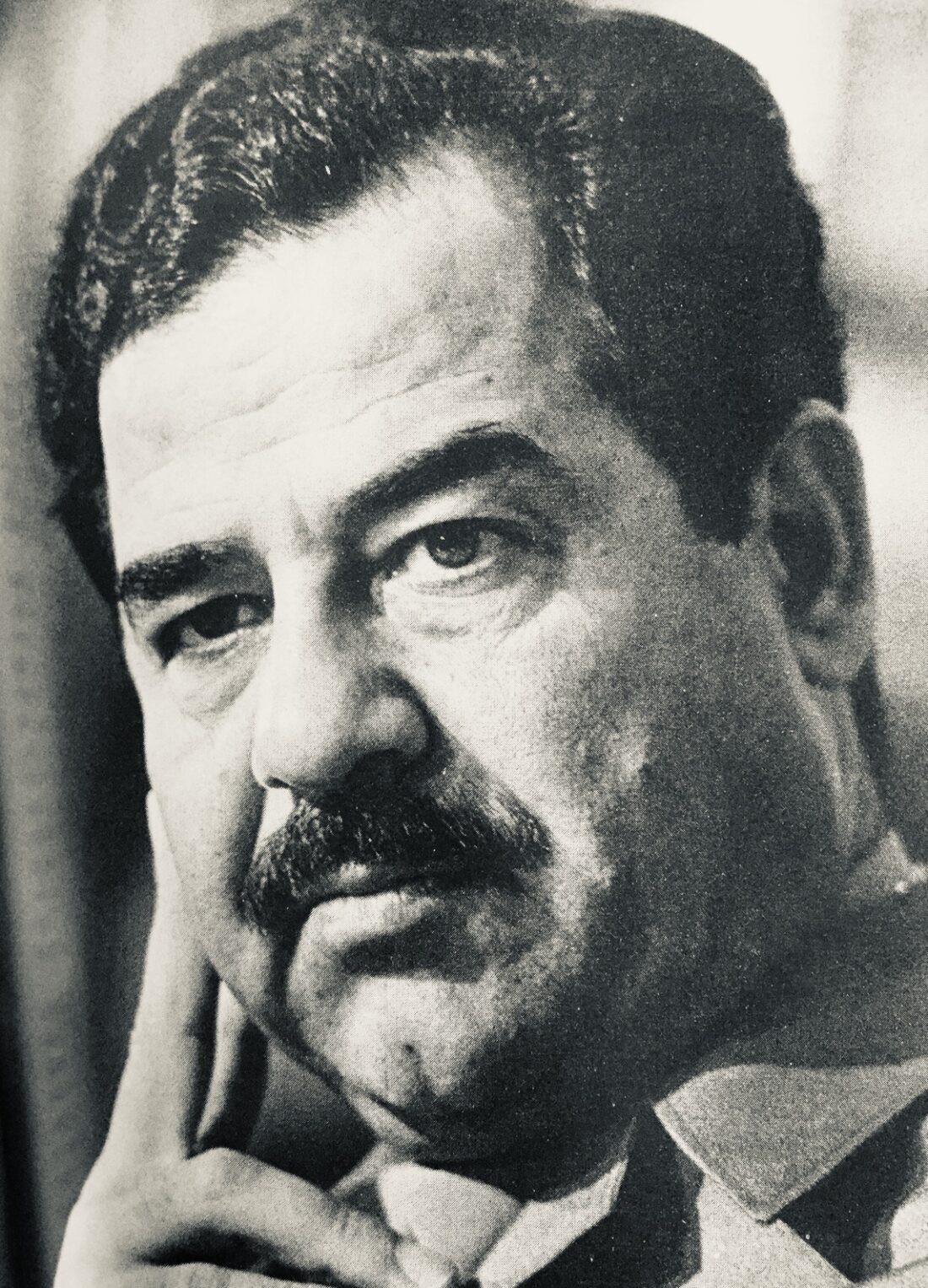

The ruling Baathist dictatorship, headed by Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, crumbled within a few weeks, and was replaced by a caretaker U.S. civilian administration governed by Paul Bremner.

Having been toppled after 24 years in office, Saddam — a Sunni Muslin in a predominately Shi’a-populated state — went into hiding, only to be captured in 2003 and executed by hanging in 2006.

Washington’s overriding official rationale for invading Iraq was to remove its biological, chemical and nuclear weapons of mass destruction. On the eve of the invasion, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell built his case for war around this sweeping claim, which turned out to be patently false.

In fact, Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction had been dismantled or destroyed by United Nations inspectors following the first Gulf War in 1991, which broke out after Iraq occupied and annexed neighboring Kuwait in 1990. So the hunt for such weapons from 2003 onward was essentially an exercise in futility, a waste of time and resources.

But as supporters of the invasion have always insisted, the removal of Saddam, an enormously disruptive and destabilizing force, was a worthy goal in itself.

Saddam, who ascended to the presidency in 1979, grossly interfered in the internal affairs of his neighbors, threatened Israel, fired 39 Scud missiles at Israeli cities during the first Gulf War, and paid subsidies to Palestinian families in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip whose sons had been killed during the second intifada.

With the dissolution of Baathism in Iraq — a major Arab state that had competed with Egypt and Syria for dominance in the Arab world — power shifted to the majority Shi’a Muslims, and has remained there ever since. As part of this transformation in governance, the Kurds, the largest ethnic group in the region to remain stateless, established a semi-autonomous enclave in northern Iraq with the approval of the U.S. occupation force.

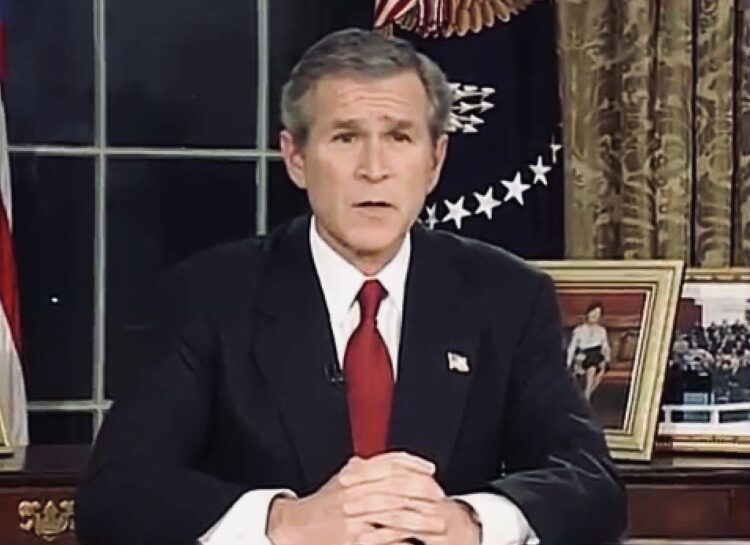

On May 1, 2003, U.S. President George W. Bush proudly stood on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln and, in a grandiose “mission accomplished” statement, optimistically declared an end to combat operations in Iraq, not realizing that a long and bloody road lay ahead.

Shortly after U.S. officials disbanded the Iraqi army and purged Baathist bureaucrats from the civil service, a nation-wide insurrection broke out. It was spearheaded by Al Qaeda operatives and disaffected Iraqi army officers. Suicide bombers targeted Americans, their local allies and United Nations personnel, including the UN’s special representative in Iraq, Sergio Vieira de Mello, who was killed by a bomb blast.

As the chaos deepened in 2004, U.S. Marines fought Iraqi rebels in a major battle in Fallujah, while Al Qaeda, led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, mounted attacks against Shi’a holy sites in Baghdad and Karbala. He was killed by a U.S. air strike in 2006.

The violence fueled sectarian hatred, which degenerated into a full-fledged civil war in the winter of 2006, when Sunni extremists destroyed an important Shi’a mosque in Samarra. At least 200,000 Iraqi civilians and 50,000 Iraqi soldiers died during this period of turmoil, upheaval and uncertainty.

With Iraq spiralling into dysfunction, Iran — Iraq’s regional rival and the Middle East’s preeminent Shi’a state — exploited the power vacuum for its own strategic ends.

Iran, which had fought an eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s that ended in a stalemate, enmeshed itself in Iraq’s politics and economy as Iraqi Shi’a Muslims took control of the country. Shi’a parties gained a parliamentary majority in 2005. Nouri al-Maliki, a Shi’a with close ties to Iran, was appointed prime minister in 2006.

As the insurgency expanded, Iran funnelled weapons to rebels. According to the Pentagon, more than 600 U.S. troops were killed by Iranian-backed fighters, a figure representing about one-sixth of the total casualties sustained by the United States.

By about 2008, the American commander in Iraq, General David Petraeus, temporarily succeeded in stamping out the rebellion. At this juncture, 170,000 U.S. troops were stationed in Iraq.

On August 31, 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama announced that the U.S. mission in Iraq would be wound up. Toward the close of 2011, the last American combat soldier departed, leaving behind a garrison to train the reconstituted Iraqi armed forces. By then, 4,487 U.S. soldiers had been killed in Iraq, with an additional 32,000 having been wounded. As well, 3,600 military subcontractors lost their lives in Iraq.

Recently, U.S. Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin said that American troops will remain in Iraq in a non-combat role at the invitation of the Iraqi government.

In 2013, Islamic State emerged with a vengeance in Iraq.

An Al Qaeda splinter group, Islamic State was remarkably successful. It defeated the Iraqi army in a momentous battle near Baghdad, captured a string of Iraqi cities, notably Mosul and Tikrit, and established a caliphate in about 40 percent of Iraq. By 2017, U.S., Kurdish and Iraqi forces had driven Islamic State out of its strongholds, assassinated its leader, and obliterated its caliphate.

After the outbreak of Syrian civil war in 2011, Islamic State entrenched itself in wide swaths of Syria, particularly in its southeastern and northern provinces, where a small U.S. expeditionary unit of some 900 troops is based.

This force, aided by Syrian Kurdish fighters, has confronted Islamic State in periodic battles and continues to block a vital road that Iran would dearly like to seize so as to ferry arms and munitions to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

In retrospect, the American invasion of Iraq, which cost taxpayers about $1 trillion, was both a success and a failure.

The Bush administration’s argument that Saddam posed a clear and present danger to the entire region was absolutely true. Viewed from this perspective, the elimination of Saddam’s vicious and unpredictable regime was justified. Saddam and his circle of cronies had to be excised like a cancer. With their demise, Iraq gradually transitioned from autocracy to democracy, though Iraq is mired in endemic corruption and is hardly a model of Jeffersonian democracy.

Yet what transpired after Saddam’s fall was plainly disastrous. Iraq plunged headlong into a seemingly endless cycle of violence, sectarianism and bedlam, all of which have receded of late.

Iran — Israel’s arch enemy — emerged strategically stronger, becoming the dominant foreign power in Iraq, one of the wealthiest Arab countries in terms of its natural resources.

The full story has yet to play out, but for now, Iran looms large in Iraq.