Ukraine has loomed large in Jewish history, a point that comes across clearly enough in A Journey Through The Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter: From Antiquity to 1914, a cross-Canada travelling exhibition which runs in Toronto until July 19.

First shown in Vaughan, a suburb north of Toronto, and then in Winnipeg, a major center of the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada, it opened in Toronto on July 8 at the St. Vladimir Institute in conjunction with the Ukrainian Museum of Canadian History.

After Toronto, it will be on display in Edmonton and Montreal. And there is a possibility that it will travel to Israel as well.

Co-funded by the Canadian government, the multi-media exhibition offers a wide-ranging account of the checkered historical experience of Ukrainians and Jews up to the end of Russian and Austrian rule in Ukraine.

It’s the brainchild of The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, a privately organized initiative launched in 2008 by a group of individuals from Canada, United States, Ukraine and Israel. Among them are Irwin Cotler, the former Canadian minister of justice; Abraham Foxman, the director of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith; Yakov Dov Bleich, the chief rabbi of Ukraine, and Amos Oz, the Israeli novelist.

It was founded on the premise that Jews and Ukrainians have much to gain by better understanding and appreciating their respective historical experiences in all their complexity, addressing embedded stereotypes and deepening awareness of periods of both peaceful coexistence and mutual tension.

The exhibition examines these issues and themes. And one leaves it with the impression that Ukrainians and Jews have influenced each other’s cultures to a remarkable degree.

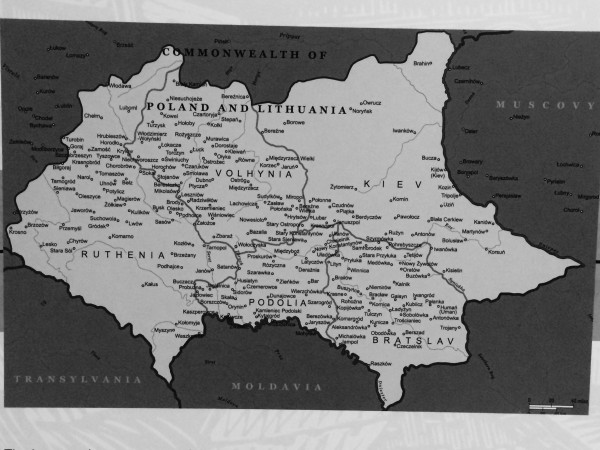

By the end of the 19th century, as one brochure points out, Ukraine had the highest concentration of Jews in the world, with about 30 percent of the Diaspora living in “ethnographic Ukrainian territories.” In parts of Ukraine west of the Dnieper River, Jews comprised 10 to 15 percent of the population.

Not surprisingly, Jews and Ukrainians influenced each other linguistically and culinarily.

Yiddish words such as “moiry” (to be afraid), “tsuris” (trouble), “broigis” (to be angry at someone) and “metsia” (a bargain) have crept into the Ukrainian language.

And according to Hebrew University scholar Wolf Moskovich, around 70 percent of the surnames of Ukrainian Jews are derived from the towns and villages of Ukraine in which they resided.

When it comes to food, the similarities are striking, as I discovered while sampling some of the kosher food at the exhibition.

Among the common foods Ukrainians and Jews consume are braided bread, beet soup, stuffed cabbage rolls, pancakes filled with cheese, shredded potato pancakes, stuffed dumplings, poppy seed rolls, honey cake and, of course, dill pickles.

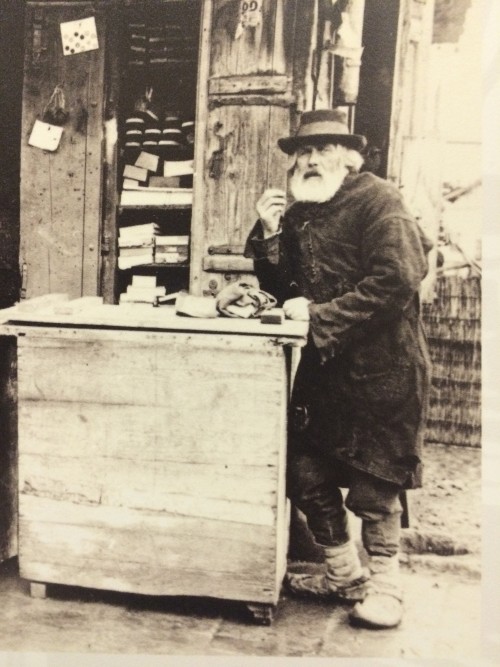

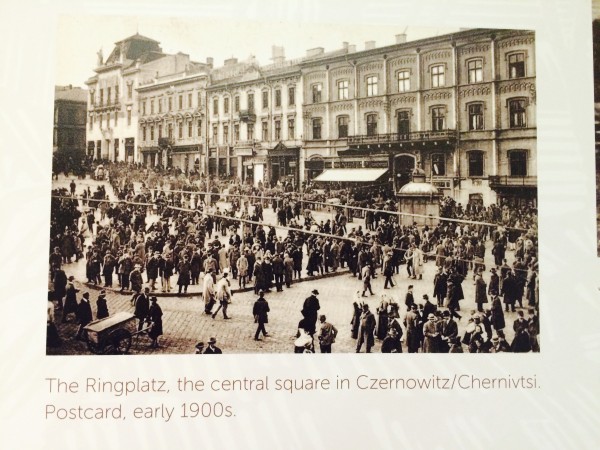

Jewish traders and merchants settled in coastal towns on the Black Sea more than 2,000 years ago. Known as Krymchaks, they were later joined by Karaites, a non-rabbinic sect from Persia. In Crimea, Jews, Turks, Tatars and Arabs played a role in the slave trade. In Lviv, Jews were instrumental in its rise as a hub of international trade and commerce. In Chernivtsi, Jews were prominent in business and the arts.

Jews and Ukrainians lived in harmony as neighbors, but antisemitism reared its ugly head at times. Jewish middlemen who managed the mines, fields and mills of Christians could find themselves caught between the nobility and the peasantry. During the infamous 17th century Cossack rebellion, led by Bohdan Khmelmytski, tens of thousands of Jews perished in pogroms. Polish landowners and Roman Catholic clergymen were also killed in these violent outbursts.

During the course of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569-1795), Jews enjoyed a high level of communal autonomy, particularly in the fabled shtetls, which produced a vibrant folk culture but which were nonetheless bastions of stultifying tradition and obscurantism and bitter class conflict.

Chassidism flourished in the Ukrainian lands, and so did a Yiddish and Hebrew publishing industry. The exhibition also touches on the Haskalah, the challenges of modernization, Jews under Austrian administration in Galicia, Bukovina and Trans-Carpathia, and the relationship between Ukrainians and Jews in Galicia.

On a darker note, Jews during the Russian epoch were generally confined to the Pale of Settlement, which was not abolished until the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Pogroms broke out in Odessa (1871), throughout the Russian empire between 1881 and 1882 and in Kishinev in 1905 and 1906. During this turbulent period, Mendel Beilis, a Jew from Kiev, was charged with using the blood of a Christian child to bake matzoh.

After the formation of the short-lived Ukrainian state, Yiddish was recognized as a national language and Jews were well represented in the Rada, the Ukrainian parliament.

Canada’s minister of finance, Joe Oliver, a descendant of Ukrainian Jews who immigrated to Canada about a century ago, gave the keynote speech at the official launch of the exhibition in Toronto.

Jews and Ukrainians, he noted, have lived in epochs of amity and strife and hew to what he described as “a shared historical narrative.”

Canada, he said, has the largest Ukrainian community outside Ukraine, with 1.2 million Canadians of Ukrainian descent living here.

Oliver said that Canada and Ukraine enjoy close relations and that Ottawa vigorously opposes Russia’s occupation of Crimea.

Paul Grod, the president of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, said that Jewish and Ukrainian Canadians have worked harmoniously on various issues. In the past, he added, common enemies have tried to sow divisions between Jews and Ukrainians.