Robert Ripley believed there is an infinity of strangeness in the world and capitalized on it to his advantage. Or as he might have told his legion of admirers, paraphrasing the entertainer Al Jolson, “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

A newspaper cartoonist who parlayed a child-like sense of wonder and curiosity into a personal fortune, he was the master of the bizarre, the weird, the grotesque and the fantastic. He understood that human beings love to be shocked, at least for a little while.

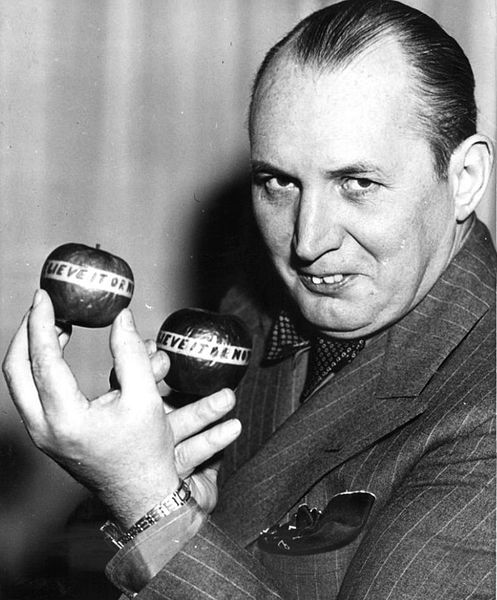

Armed with this knowledge, he built the Believe It Or Not empire, which was constructed on a foundation of arcane factual trivia, which people consumed with gusto and relish.

On Tuesday, Jan. 6, the PBS network’s American Experience series will broadcast Ripley: Believe It Or Not, an intriguing biopic that documents the life and career of a smalltown boy whose popularity reached epic heights in the 1930s and 1940s.

Born in Santa Rosa. California, in 1890, Ripley was a shy, awkward kid, a bit of an outcast and loner, who turned to drawing for solace. At the age of 19, after a magazine published his first cartoon for the princely sum of $8, he moved to San Francisco in search of a job. A local newspaper hired him as a cartoonist, and he never looked back.

Ripley was fired from two newspapers, but that didn’t deter him. He went to New York City, where he landed a position as a sports cartoonist on the Globe and Commercial Advertiser at $25 per week.

On a slow day one winter, he devised the “believe it or not” cartoon. It so impressed editors that they sent him on a four-month cruise to some of the world’s most exotic places. India, in particular, bowled him over, and China fascinated him. He returned to the United States a changed man.

Ripley, who would visit 201 countries during his travels, signed a book deal to embellish his experiences abroad. It struck a chord with readers, who were ready to have their conception of reality challenged.

Smelling a money maker, the publisher William Randolph Hearst offered Ripley $100,000 per annum, a fabulous salary back then, to produce seven cartoons a week for his snydication service. Hearst was a good judge of talent. Ripley received up to 3,000 letters a day from readers with suggestions for cartoons. With Hearst’s financial backing, Ripley set off on another lenghty overseas trip to dredge up yet more oddities.

As the film points out, Ripley was most definitely not a one-man show. He relied enormously on his behind-the-scenes researcher and fact checker, Norbert Pearlroth, an Austrian Jew who daily frequented the New York Public Library for fresh material. With Ripley declining to give him credit or publicity, Pearlroth remained an anonymous figure.

Ripley, however, became a celebrity. Eventually, he would extend his franchise to film, radio, TV and odditoriums, where his oddities were displayed.

By the mid-1930s, with America mired in a great depression, Ripley was earning an annual income of $500,000. This wealth enabled him to buy several luxuriously-appointed homes and a yacht. Ripley’s winning formula inspired a succession of copycats, but none could duplicate his success.

Ripley, who died in 1949 of a heart attack, was a one-of-a-kind figure, an artist and entrepreneur who cast a discerning eye on the unconventional and unusual and made millions off them.