The Vietnam War was my war, so to speak.

Let me explain.

As it inexorably escalated from an insurgency in the 1950s into a full-blown conflict in the 1960s, prompting anti-war protests in the United States and other countries, I watched it unfold from the safety of my home in Montreal.

I read David Halberstam’s dispatches in The New York Times and I watched Walter Cronkite’s newscasts. Occasionally, I attended demonstrations against the war. Like so many of my contemporaries, I believed the United States had embroiled itself in an unwinnable war, should withdraw from South Vietnam and let the Vietnamese sort it out themselves.

Years later, following the unification of South Vietnam and North Vietnam and the end of the protracted war, my interest in Vietnam remained at a fairly high pitch. So much so that I travelled to Vietnam twice, finding it an enchanting country with friendly and inquisitive people.

Vietnam has moved on since the U.S. military intervention, but the memory of the war lingers on in my mind. The Vietnam War, a 10-part, 18-hour series by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick currently playing on the PBS network, has brought it all back.

Ambitious in scope, it takes a viewer from the French conquest of Vietnam in 1858 to the present. At once objective and personal, their documentary traces the history of Vietnam’s struggle for independence through a strong narrative and interviews with former soldiers, journalists and diplomats. Judging by the first four episodes, it’s an excellent piece of work.

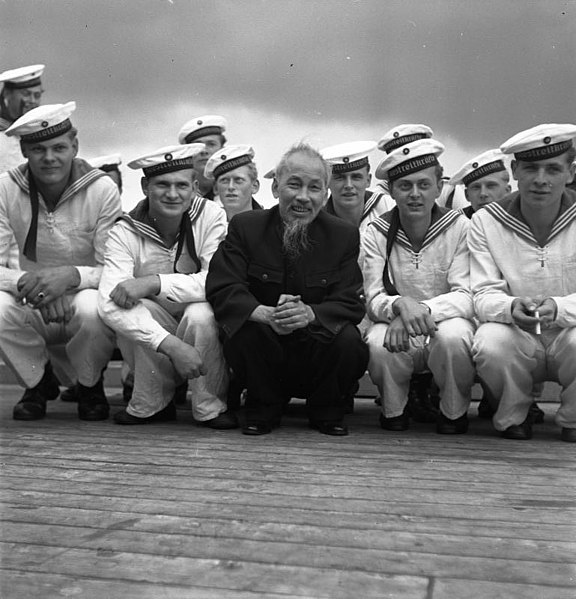

Burns and Novick deal briefly with the 19th century colonial period before examining the short-lived Japanese occupation during the early 1940s. As astonishing as it may sound today, the United States aligned itself with Vietnamese nationalist icon Ho Chi Minh during World War II, supplying his guerrillas with arms.

With Japan having been driven out by Vietnamese insurgents, French troops returned to Vietnam in 1946, only to face armed resistance. As the Cold War intensified, the Soviet Union offered aid to Ho Chi Minh, while the United States sent supplies and a small number of military advisors to French forces.

Decisively defeated at the 1954 battle of Dien Bien Phu, France withdrew from Vietnam. Under the Geneva accords, Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel, a temporary arrangement that hardened into an implacable fact.

In the south, power lay in the hands of Ngo Dinh Diem, an authoritarian figure whose government was riddled with corruption and weighed down by unpopularity. Ho Chi Minh, his northern adversary, opposed the division of Vietnam and was determined to unite it under his authority. And so the seeds of a civil war were planted.

Fearing the spread of communism from North Vietnam, President Dwight Eisenhower expanded the U.S. presence in South Vietnam. He did so by stealth. As Burns and Novick observe, the American military involvement, overseen by five presidents, began in secrecy. America’s embroilment in Vietnam would be the most divisive era in U.S. history since the 19th century Civil War. The first U.S. soldier serving in Vietnam was killed in 1955. By war’s end, 58,000 U.S. troops had fallen — not to mention hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese Viet Cong guerrillas, North Vietnamese soldiers and two million Vietnamese civilians.

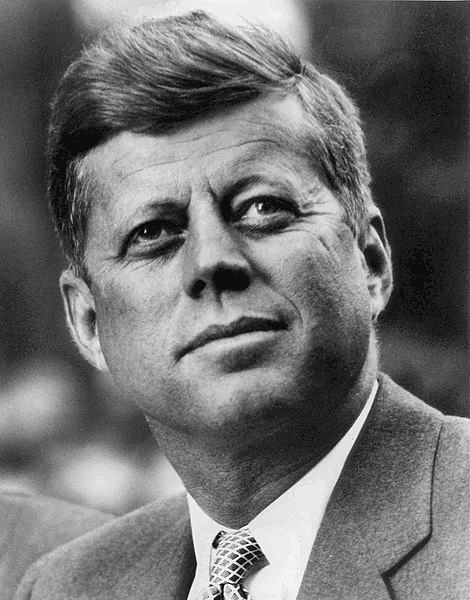

John F. Kennedy, caught between his idealism and his sense of Realpolitik, opted to conduct a limited war in South Vietnam. He sent in Green Beret commandos to organize mountain tribes and train the South Vietnamese army. And in the hope of winning the “hearts and minds” of peasants in 14,000 hamlets, Washington dispatched all manner of experts to improve their standard of living.

For a while, the United States appeared to be winning the war, but it was a grand illusion. Forty percent of South Vietnam was held by the Viet Cong. Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, realized from the outset that Vietnam was the “biggest damn mess.” Diem’s assassination added another layer of complexity to the situation, resulting in a crisis of legitimacy in Saigon, the capital. In revolving door fashion, eight different governments ruled South Vietnam from 1964 to 1965.

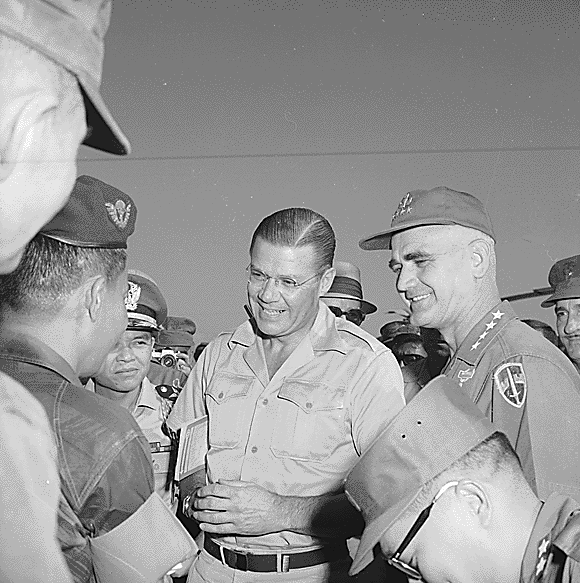

Johnson was a reluctant warrior, being loath to send combat troops to South Vietnam. But events on the ground drew him into the Vietnamese quagmire. On the recommendation of Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara, Johnson committed U.S. airpower to exert pressure on North Vietnam, but the tactic backfired. Le Duan, who supplanted Ho Chi Minh as Vietnam’s operational leader, fought back ferociously. The Americans underestimated the resolve of the North Vietnamese.

William Westmoreland, the four-star general in charge of the U.S. war effort in Vietnam, urged Johnson to send yet more combat troops. By the close of 1967, more than 500,000 American soldiers were stationed in South Vietnam and about 20,000 U.S. troops had been killed there, a development that led to widespread protests in the United States.

Burns and Novick tell this story with vigor and elan, though it’s abundantly clear they’re skeptical of the U.S. project in Vietnam.