The War of Attrition is virtually forgotten today, lost in the mists of time.

Overshadowed by the 1967 Six Day War, Israel’s greatest military triumph, it erupted 50 years ago on March 8, 1969 and lasted 17 months, until a ceasefire hammered out by American diplomacy ended it on August 7, 1970.

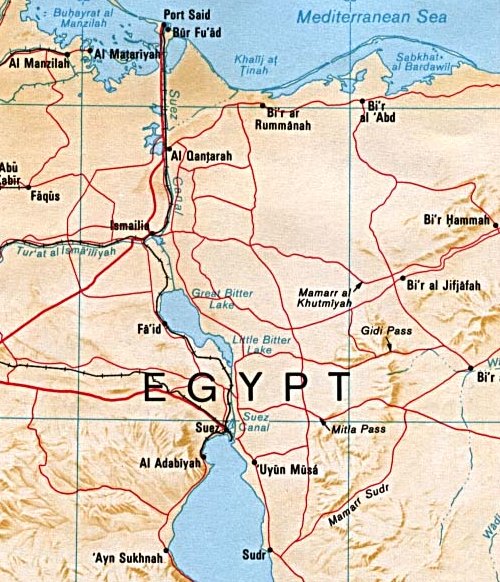

The War of Attrition, an extension of the fighting that broke out between Israel and Egypt shortly after the Six Day War, unfolded primarily along the length of the closed Suez Canal. But it also flared on the Golan Heights and in the Jordan Valley, respectively pitting Israel against Syria and Israel against the Palestine Liberation Organization and Jordan.

Eventually, the War of Attrition morphed into a proxy war between the United States, Israel’s ally, and the Soviet Union, Egypt’s chief arms supplier.

During the Six Day War, Israel decisively defeated Egypt and swept victoriously to the Suez Canal. Egypt signed a truce with Israel on June 11, 1967, but hostilities resumed on July 1 as Egyptian commandos attacked Israeli soldiers in a clash on the eastern bank of the canal.

Two months later, at the Khartoum conference in Sudan, Arab League states, spearheaded by Egypt, unveiled the “three nos” policy that guided the Arab world for the next decade — no peace, recognition or negotiations with Israel.

Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, determined to regain the Sinai Peninsula that Israel had so easily conquered, persuaded the Soviet Union to resupply his army and air force. He then ordered his troops to launch raids against Israeli soldiers hunkered down in trenches along the canal and instructed his artillery batteries and air force to strike Israeli positions deeper in the Sinai.

In March, Nasser officially acknowledged the war with his announcement that Egypt no longer recognized the truce that had gone into effect after the Six Day War. “What was taken by force will be returned by forced,” he declared, launching a war intended to weaken Israel and force it to withdraw from territories it had captured during that war.

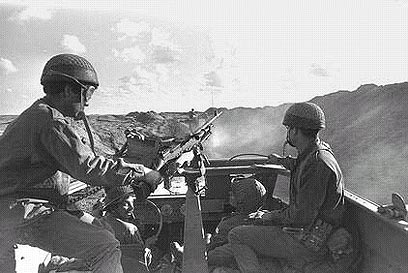

Israel, intent on keeping the Sinai, responded by counter-attacking. In short order, artillery exchanges and aerial combat broke out on virtually a daily basis.

On October 21, Egypt struck a heavy blow as Egyptian naval vessels, armed with the latest Soviet anti-ship missiles, sunk the Israeli destroyer Eilat in the Mediterranean Sea, killing 47 sailors. It was the first instance in naval warfare that a missile had destroyed a surface vessel. In response, Israel shelled Egyptian oil refineries and depots near the city of Suez. This, in turn, triggered more artillery and air duels.

The war escalated in 1968 as Israel and the PLO fought a major battle in March in the Jordanian town of Karameh. King Hussein’s Arab Legion intervened on the side of the Palestinians. Although Israel destroyed a PLO base in Karameh, the Palestinians inflicted heavy casualties on the Israelis and declared victory. On the Golan, Israeli and Syrian forces clashed in occasional skirmishes.

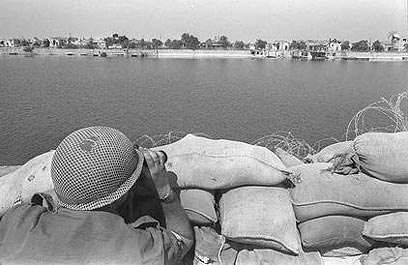

During the course of that year, Israel began building the Bar-Lev Line, a heavily fortified bunker system along the canal named after the Israeli chief of staff, General Chaim Bar-Lev. It was deemed necessary to lower Israel’s increasing casualties.

On March 8, 1969, as Nasser officially proclaimed the start of the War of Attrition, Egypt let loose with a massive air and artillery barrage. Israel retaliated in kind. While visiting his men on the front lines the following day, the Egyptian chief of staff, General Abdul Munim Riad, was killed during an Israeli mortar attack.

Striking key Egyptian bases more aggressively, Israel launched a commando raid on Green Island in July, killing 80 Egyptian troops and losing six of its own soldiers. With Egyptian artillery bombardments claiming the lives of still more Israeli soldiers, Israel took the war to Egypt’s heartland. On October 30, Israeli commandos reached the Nile River, damaging an electric transformer station, two dams and a bridge. On December 26, Israeli commandos landed at another Egyptian base, Ras Gharib, carrying back a state-of-the-art P-12 radar station.

Israel, having received its first batch of F-4 Phantom jets from the United States, intensified its air raids on Egyptian military facilities. During these sorties, Egyptian missiles downed several Israeli aircraft, capturing its pilots.

On January 22, 1970, Nasser flew to Moscow and asked the Soviet regime for more sophisticated anti-aircraft batteries and jets. He also requested the presence of more Soviet personnel — advisors and mechanics — to maintain Egypt’s military equipment. The Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev, was initially reluctant to be drawn in so deeply. But finally relenting, he complied with Nasser’s requests. By June, 10,000 to 12,000 Soviets, and 100 to 150 pilots, were stationed in Egypt, as were Cuban advisors.

On the day Nasser held talks with Brezhnev, Israeli paratroopers and naval commandos struck an Egyptian base on Shadwan Island, killing 70 soldiers and dismantling a Soviet-made radar station. Two weeks later, Egyptian frogmen damaged Israeli ships anchored in the southern port of Eilat.

By March, new Soviet anti-aircraft batteries had been installed near the canal by Soviet technicians, prompting Israel to bomb them from the air.

The following month, the Israeli Air Force carried out deep-penetration raids on the western side of the canal, hitting Egyptian bases. In one raid, an Israeli Phantom jet accidentally bombed a school in the town of Bahr el-Baqar, killing 46 school children and injuring over 50. Responding to international condemnation, Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir ordered a cessation of such raids.

On June 25, in an ominous development, an Israeli jet bombing Egyptian forces on the canal was pursued by Soviet-piloted MIGs. Five days later, the new Soviet anti-aircraft batteries shot down two Israeli Phantoms, capturing two pilots and a navigator.

On July 30, in an unprecedented dogfight between Israeli and Soviet jets, Israel downed four MIGs and badly damaged a fifth which crashed. In an ambush, the Soviets brought down two Israeli jets.

Concerned by the upsurge of fighting, U.S. Secretary of State William Rogers worked out a ceasefire that went into effect on August 7. Egypt, supported by the Soviet Union, violated it by moving anti-aircraft batteries closer to the canal.

Nonetheless, the truce more or less held. By war’s end, 1,424 Israeli soldiers had been killed, compared to 776 during the Six Day War.

On September 28, Nasser died, felled by a heart attack. His successor, Anwar Sadat, observed the ceasefire, but warned Israel he would go to war unless a more permanent political arrangement could be put into place. Israel, feeling overly confident, rejected an Egyptian plan submitted by Sadat in a speech on February 3, 1971.

Reaffirming Egypt’s commitment to recapturing the territories seized by Israel in 1967, Sadat called on Israel to redeploy its forces away from the canal, which, he said, would be reopened to international navigation.

Some Israeli cabinet ministers, notably Foreign Minister Abba Eban, urged his colleagues to accept Sadat’s proposal. Meir rejected the plan. Egypt continued its preparations for a new war, while ejecting 18,000 to 20,000 Soviet advisors and experts from its soil.

Israel’s rejection of Sadat’s pace plan proved to be catastrophic.

The Yom Kippur War broke out on October 6, 1973 as Egyptian and Syrian forces launched punishing offensives in the Sinai and the Golan. The war cost Israel dearly. In three weeks of fighting, Israel lost 2,656 soldiers and tons of military equipment.