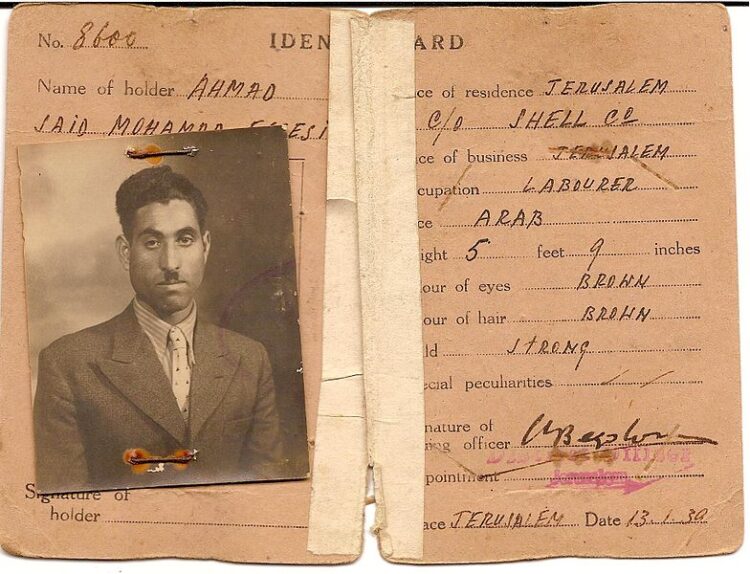

Of all of the thorny issues exacerbating Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians, the “right of return” is doubtless the most complex one. It turns on the unwavering demand by Palestinian refugees to go back to their original homes in what was Palestine and what has been Israel since its declaration of statehood in 1948.

This pivotal issue is examined in minute detail by Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf in their sober and engaging work, The War Of Return: How Western Indulgence Of The Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed The Path To Peace (All Points Book).

The authors are both Israelis. Schwartz is a researcher who focuses on the Arab-Israeli dispute. Wilf is a former Labor Party member of the Knesset. Strong proponents of the two-state solution, they say they have supported all of Israel’s major efforts to reach a peace agreement based on this formula. “We believed that once the Palestinians would be able to establish their own state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, there would be peace,” they write in the foreword.

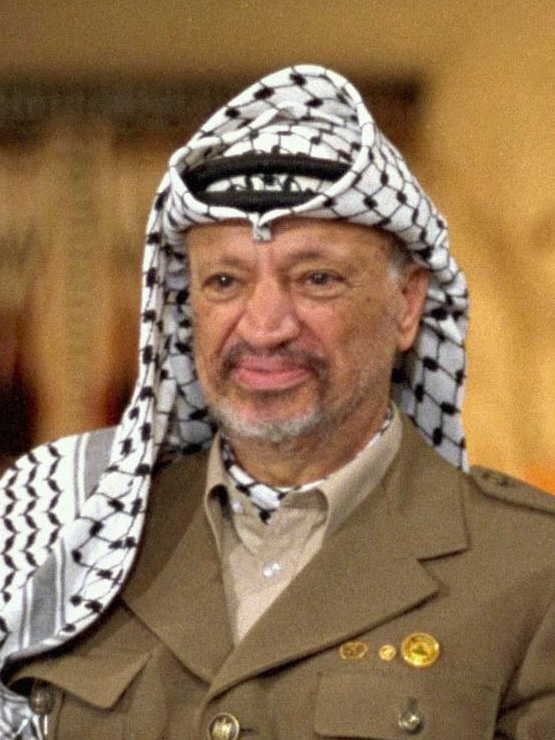

But when the Palestinian Authority under two different leaders — Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas — rejected diplomatic opportunities in 2000 and 2008 to achieve this objective, and when the first negotiating process was followed by a sustained campaign of terrorism, they began to have second thoughts. “And so we each found ourselves increasingly doubting our basic assumptions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — that this was a territorial conflict that could be solved by partitioning the land into two states …”

What went wrong? What were they missing?

The Palestinian refugee issue.

In their view, it has not received the serious attention it requires by either Israel or the international community. Yet it is the root cause of the conflict and the festering sore that perpetuates it.

“The Palestinian conception of themselves as ‘refugees from Palestine’, and their demand to exercise a so-called right of return, reflect the Palestinians’ most profound beliefs about their relationship with the land and their willingness or lack thereof to share any part of it with the Jews.

“The Palestinian demand to ‘return’ to what became the sovereign state of Israel stands as a testament to the Palestinian rejection of the legitimacy of a state for the Jews in any part of their ancestral homeland.”

From this point forward, Schwartz and Wilf launch into a comprehensive discussion of the Palestinian attitude toward Jewish self-determination and the right of return, both of which are intertwined.

Before he was killed in battle during Israel’s War of Independence, the commander of Palestinian forces in and around Jerusalem, Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini, wrote a letter to his son in which he declared, “The Jews have no right to this land.” According to Schwartz and Wilf, it “reflected the position of all sections of Palestinian society at the time.”

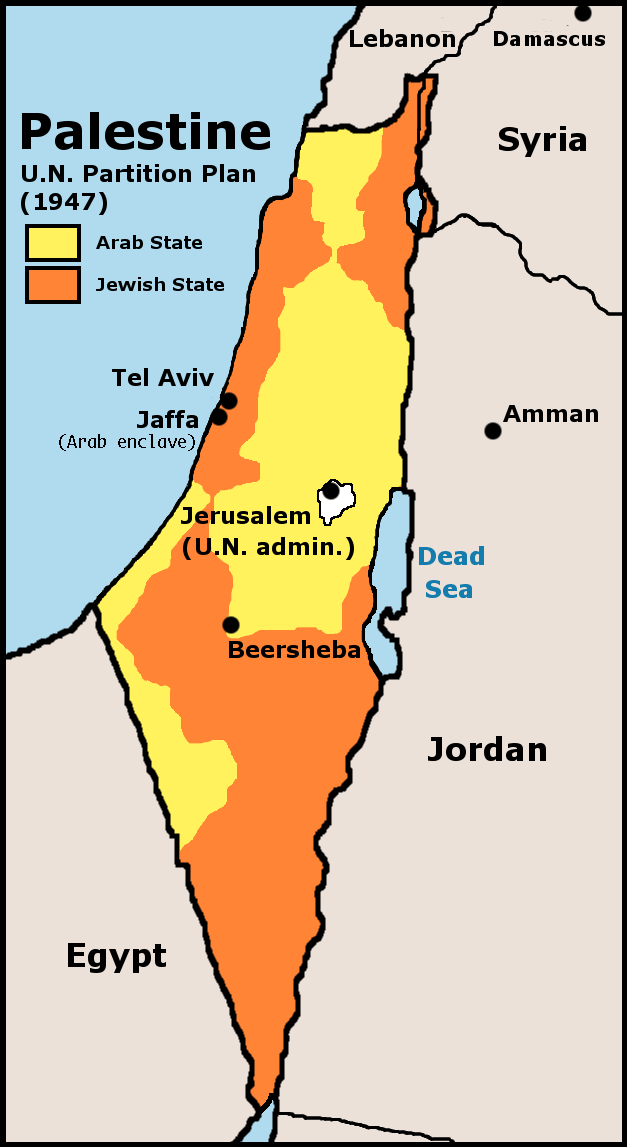

While the Jews of the Yishuv accepted the 1947 United Nations plan partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, despite the fact that 47 percent of the inhabitants of the Jewish state would be Arabs, the Palestinians could not come to terms with partition and called for an Arab state. At most, Jews could live in Palestine as dhimmis, or protected persons.

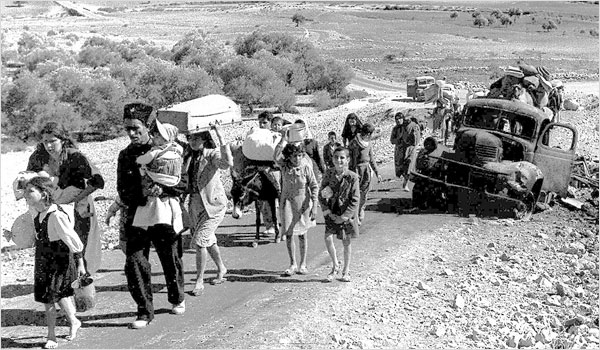

And so the stage was set for war, pitting Jews against Palestinian Arabs and the Arab world at large. During the first stage of hostilities, from November 1947 to March 1948, 100,000 Palestinians voluntarily fled, the majority being upper middle-class families. From April until June, between 200,000 and 300,000 Palestinians left. During this phase, there were some forced expulsions. Still more Palestinians were expelled from July onward.

Of the approximately 700,000 expellees, two-thirds remained within the borders of Mandatory Palestine, or in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, while the rest, about 250,000, went to neighboring Arab countries.

The 150,000 Palestinians who chose to stay became Israeli citizens.

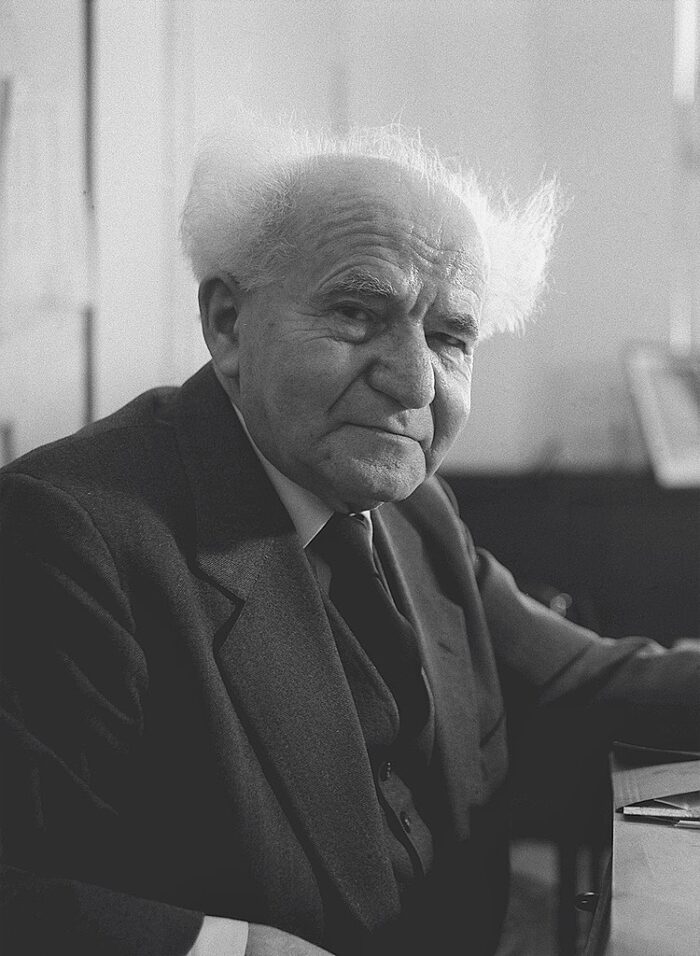

Schwartz and Wilf claim that Zionist leaders from David Ben-Gurion on down had no advance plans to expel the Palestinians, and that all the Palestinians could have remained in their homes had they accepted partition. “The Arab flight and the refugees from the war were neither inevitable nor necessary nor inherent in Zionism.”

So why did they flee? Many Palestinians feared they would be punished or killed if they fell into Jewish hands. This narrative was promoted by the Arab media especially after the Deir Yassin massacre of Palestinian villagers. “Additionally, the prolongation of the war caused the economy to suffer, and many (Palestinians) could no longer bear the hardship and turmoil.” Lastly, some fled because they did not want to be perceived as traitors.

By the authors’ reckoning, not a single Jew remained in areas conquered by Arab forces. “The Palestinian fighters sought to expel the Jews and destroy their communities,” they write, citing the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem and the Gush Etzion bloc of settlements in the West Bank.

Demolishing the Palestinian assertion that they suffered an exceptional or unique injustice, Schwartz and Wilf cite a litany of population exchanges and expulsions in the 20th century, from the exchange between Turkey and Greece to the flight of ethnic Germans from Central Europe and the Balkans, and the removal of Jews from Arab nations.

Working on the reasonable assumption that the Arabs were preparing for a second round of warfare after their defeat in the first Arab-Israeli war, and that the Palestinians would never accept Israel’s existence, Ben-Gurion decided it was necessary to deny the refugees the right to return. He and his colleagues considered them potential Fifth Columnists. “A large, hostile Arab population, which had just taken up arms to try to destroy Israel, would have been a perpetual enemy within Israel’s borders,” the authors point out.

Schwartz and Wilf contend that the concept of the right of return was devised by the Swedish United Nations mediator Count Folke Bernadotte, who would be assassinated by right-wing Zionist gunmen. Under his proposal, the refugees would have been given the option of returning.

Three months after his assassination, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 194, which was based on his plan. The resolution states that “refugees wishing to return … and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.”

With the Cold War in full swing, the United States and Britain endorsed the resolution, fearing that the presence of hundreds of thousands of refugees in Arab states would provoke instability and foment communist revolutions. The chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, William Leahy, told American Secretary of State George Marshall that the plight of the refugees was an opportunity for the West to strengthen its friendship with the Arabs.

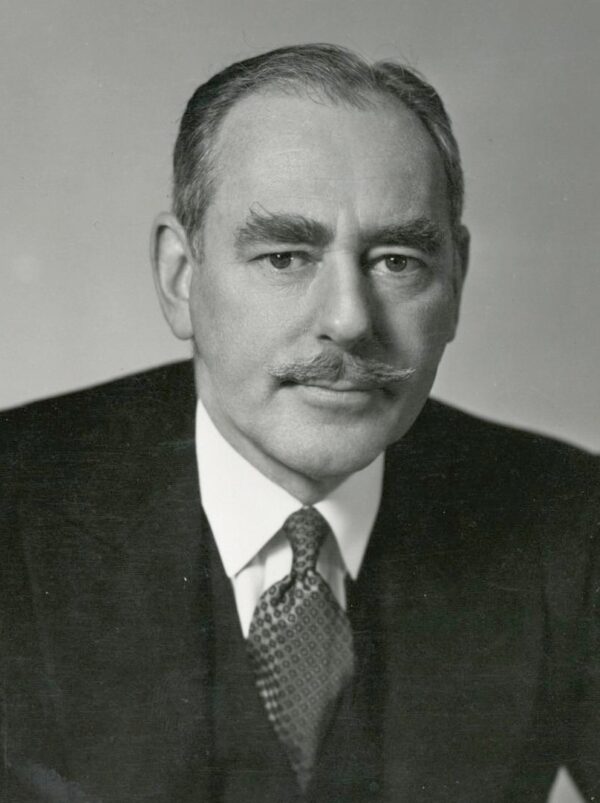

Marshall’s successor, Dean Acheson, modified U.S. policy. In 1949, he conveyed a somewhat conciliatory message to Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett: “Repatriation of all these refugees is not a practical solution. Nevertheless, we anticipate that a considerable number must be repatriated if a solution is to be found.”

President Harry Truman applied pressure on Ben-Gurion to sign on to Washington’s position and threatened to revise his attitude toward Israel if it resisted. The Israeli government responded by unveiling two separate proposals. Under the first proposal, Egypt would cede Gaza to Israel and the refugees there would be granted Israeli citizenship. Under the second plan, Israel would absorb 100,000 refugees in the context of a peace treaty with the Arabs. Each proposal was slammed as a non-starter by Arab regimes.

These fiascos were a turning point, marking the end of efforts by the Arabs and Western governments to impose a mass return of refugees to Israel without a peace treaty. From that juncture onward, the preferable solution to the refugee problem would be their economic rehabilitation in Arab countries within the framework of UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency.

The Arab League welcomed UNRWA, but on a practical day to day level, most Arab states did not really try to absorb the refugees. With the exception of Jordan, every Arab government denied the Palestinians citizenship and equal employment and educational opportunities. Lebanon feared that the mainly Muslim Palestinians would upset its delicate sectarian balance.

“Arab public opinion saw rehabilitation of the refugees as nothing less than treason,” write Schwartz and Wilf. “The refugees were hostile … because of their unwavering belief that regular employment in Arab countries would mean relinquishing their demand to return to Israel.”

In 1957, Israeli Foreign Minister Golda Meir complained that Arab states were preventing any form of integration of the refugees so as to perpetuate the Arab-Israeli dispute.

As Schwartz and Wilf strongly suggest, the refugees and their children have been the most radical of Palestinians. Largely confined to refugee camps, which became states within states in Lebanon and Jordan and the PLO’s most important base of support, the refugees developed a distinct Palestinian identity focused on “a violent and uncompromising demand for return and a complete rejection of Israel.”

“UNRWA schools (have) repeatedly emphasized the idea of a violent return to … Israel,” they add. UNWRA itself has given credence to the notion that the 1948 war is not yet finished, and that generations of Palestinian refugees should expect to return to Israel. “The Palestinians’ demand for return is only growing under the umbrella of Western blindness and indulgence,” they charge.

By no coincidence, six of the eight Palestinian terrorists involved in the abduction and murder of Israeli athletes at the Olympic Games in Munich in 1972 were the sons of refugees.

Even after the PLO grudgingly accepted Israel’s existence, though not necessarily its legitimacy, the refugee question remained at the core of its philosophy. And this is of the utmost importance because the right of return, the authors maintain, “cannot be reconciled with the right of the Jewish people to self-determination in their own state.”

They add, “In demanding sovereignty over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip without dropping their aspirations to return to Haifa, Acre and Jaffa as well, the (PLO) was saying that any change in (its) position was cosmetic, a tactical move to score points … from the West without a strategic decision to accept Jewish sovereignty.”

This is how the PLO’s so-called “phased plan” to initially settle for statehood in the West Bank and Gaza should be understood, they argue. As Arafat’s deputy, Abu Iyad, frankly said, “An independent state in the West Bank and Gaza is the beginning of the final solution. The solution is to establish a democratic state in the whole of Palestine.”

Schwartz and Wilf claim that Israel’s negotiators at the Oslo peace talks in 1993 erroneously believed that the Palestinians had made a strategic decision to divide the land between themselves and Israel, and that their demands were intrinsically territorial.

In 2002, Arafat told The New York Times that, without a solution of the refugee problem, a peace agreement could be destabilized. Arafat’s successor, Abbas, referred to this issue in 2008 when he rejected Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s offer of Palestinian statehood.

Drawing conclusions from the Palestinians’ insistence on achieving the right of return, Schwartz and Wilf write, “After more than seven decades of war, the time has come for the international community to acknowledge that the Palestinian vision of an exclusive Arab land in all of the territory from the Jordan to the Mediterranean is real, and that no peace will be possible before this vision is replaced with one that does not negate Jewish self-determination.”

Schwartz and Wilf insist that the right of return is not merely “a bargaining chip in the service of a greater goal of independence and statehood. It is actually the greater goal itself … Palestinians have constantly rejected any formulation, agreement or settlement that might foreclose this option of return, even at the price of statehood … there is abundant evidence that they are really serious about returning … they have made a conscious and deliberate choice to keep fighting for a vision in which there is no state for the Jewish people in any part of the land.”

In closing, Schwartz and Wilf argue that the Palestinians must unequivocally relinquish their right of return if there is to be peace and a two-state solution — which is still the only realistic and practical solution to a conflict that already has dragged on too long and caused far too many deaths.