Italian novelist Primo Levi theorized that ordinary people are more likely to commit atrocities than supposed monsters. As Levi, a Holocaust survivor, aptly observed, “Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.”

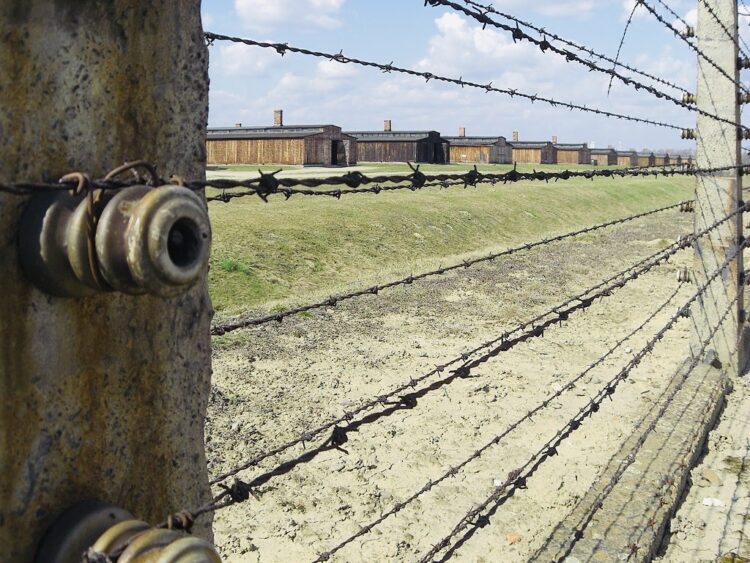

Martin Amis must have been inspired this macabre idea when he wrote The Zone of Interest, a novel revolving around Rudolf Hoss, the longest-serving commandant of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland. A fervent Nazi, he was in charge of it from 1940 until 1943 and again from 1944 until 1945, during which time 1.1 million Jews and tens of thousands of Soviet prisoners of war and Poles were killed there.

Aside from being a mass murderer, Hoss was a capable and innovative technocrat. It was he who converted Auschwitz, initially a camp for political prisoners, into vast charnel house known as Auschwitz-Birkenau. Under his methodical direction, gas chambers were installed and Zyklon-B gas was introduced into the killing process.

As a perpetrator, Hoss had few equals. Which explains why his boss, SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler, regarded him as a Nazi role model.

Hoss is at the center of Jonathan Glazer’s finely-crafted and disturbing feature film, The Zone of Interest, which is currently playing in theatres. Loosely based on Amis’ novel, it approaches the Holocaust from the viewpoint of the perpetrators rather than the victims. From this perspective, it is completely unlike Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List or Roman Polonsky’s The Pianist, both of which deservedly won a plethora of awards.

Glazer’s film, starring the German actor Christian Friedel as Hoss, is not as intense or as powerful. But it leaves a viewer riveted and, ultimately, discomfited.

Nearly one-and-a-half-hours in length, it mainly takes place in a two-storey villa and its adjoining garden on the grounds of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Hoss, his wife Hedwig (Sandra Huller) and their five children live there in a bubble of bourgeois comfort and tranquility. The gas chambers and the crematoriums are close by, but a high wall and trees keep them visually at bay.

In accordance with Levi’s supposition, the Hoss’ are the embodiment of an ordinary middle-class German family, but their ordinariness is set off by the genocidal crimes in which they are complicit. Hoss, resplendent in a pressed uniform and shiny boots, performs his job like an efficient bureaucrat. Hedwig, his dutiful wife, tends to his needs and that of their children. Little does she know that he is a sexual predator behind her back. Or that his only true love is a horse which he rides occasionally.

In sharp contrast to its chilling theme, the film begins in sylvan splendor on a bright sunny summer day as Hoss and his family enjoy a picnic on the grassy bank of a fast-flowing river near the camp. This idyllic scene is eons away from the blood-curdling realities of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The juxtaposition between the pristine beauty of nature and the murderous toll that the camp exacts on its inmates is jarring. From beginning to end, the victims are rarely seen, except for the few lucky prisoners who have been commandeered to work silently and obediently within the walls of the Hoss estate.

Hedwig, a consummate gardener, has created a paradisiacal world of lovely flower beds, lush vegetable gardens and a children’s playground in front of their abode.

Yet Auschwitz looms large.

Tall chimneys in the near distance belch black clouds of smoke and fire. Shouts, the occasional scream, and the discharge of bullets are periodically heard. The outline of an incoming train, transporting the latest batch of Jews to their collective deaths, is seen periodically. A forced laborer fertilizes a patch of green with the ashes of the dead. Hoss, having found a jawbone in the river while on a swim, jumps out of the water with alacrity and rushes back to furiously scrub himself and his children with soap.

Beyond these images and noises, the Holocaust-in-progress is something of an abstract reality in The Zone of Interest. Glazer focuses on Hoss and his family, who are virtually insulated from the palpable madness just beyond the perimeter of their tidy home.

Hoss, as ably portrayed by Friedel, is quiet, self-composed and ambitious, eager to please superiors who have committed themselves to the gruesome but ideologically necessary task of murdering the Jews of Europe. In one telling scene, he confers with earnest executives in suits from Topf & Sons, the German company that supplied Auschwitz-Birkenau with its crematoriums. Hoss listens carefully as they coldbloodily explain the nuances of their high-tech ovens.

Their clinical conversation personifies what the German Jewish philosopher and political scientist Hannah Arendt succinctly described as the “banality of evil.”

Jews, per se, are hardly mentioned in the film. Hedwig refers to a “Jewess” when she shows off a fur coat appropriated from a Jewish woman who had the misfortune of being sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. In another instance, one of Hoss’ younger sons experiences a spasm of fear when the word “Jew” comes up in discussion.

Hedwig, having grown accustomed to the comforts of the villa, is shocked and disappointed when Hoss informs her he is being transferred to a concentration camp near Berlin. Hedwig adores the villa, and as her visiting mother proudly notes, her pampered life there is a sign that she has comfortably “landed on her feet.”As Hedwig, Huller delivers a substantive performance.

In his new position, Hoss is in charge of organizing the deportation of Hungary’s 700,000 Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The antiseptic scene in which this monstrous crime is casually planned by Hoss and his uniformed colleagues is typical of the bloodless and heartless manner in which Nazi officials went about the business of planning genocide.

The Zone of Interest, however, is not about the Holocaust as it unfolded, but about the legion of perpetrators who compartmentalized their lives in carrying out the wholesale slaughter of millions of European Jews. Ruthless Nazi killers like Hoss could be reading a German fairy tale to one of his children one night and attending to the murder of thousands of newly-arrived Jews the following day.

As Levi correctly noted, the capacity of ordinary human beings to sink to abysmal depths is what should alarm all of us.

As the film reaches its denouement, Glazer adds a contemporary touch, inserting a brief clip of the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum and memorial, a site of pilgrimage and contemplation today. Polish workers, brooms and brushes in hand, sweep a former gas chamber and clean an oven that devoured countless people. The camera then pans on a big glass case filled to the brim with thousands of discarded shoes.

The most appalling crime of the twentieth century has not been forgotten. Hoss’ sickening handiwork is on full display in the camp nearly eighty years after he was hanged on its grounds.