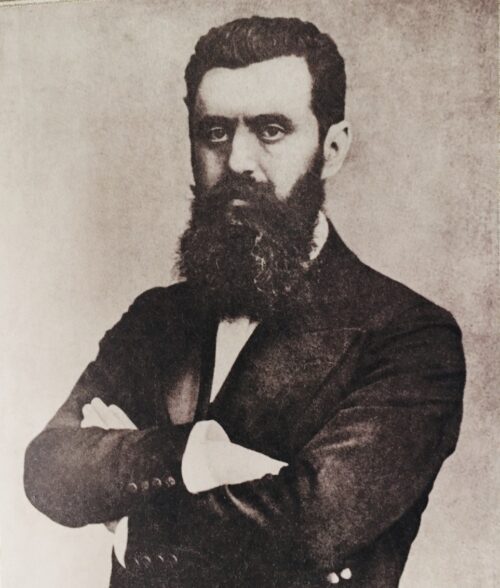

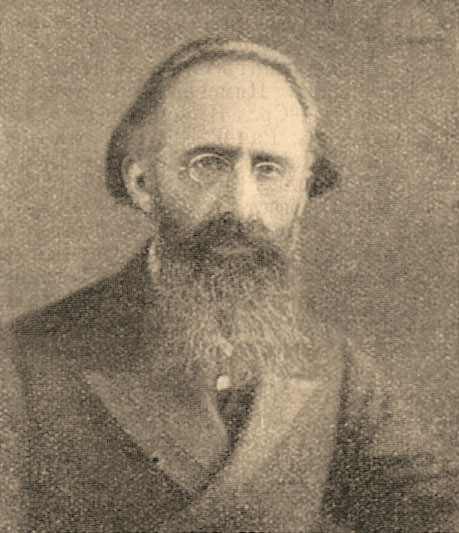

Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, was proof of the theory that one man can make a difference. Against the greatest of odds, he laid the foundation for the birth of Israel, an event he presciently predicted at the turn of the 19th century.

A visionary, prophet and leader, Herzl was an unlikely Jewish nationalist, a secular, cosmopolitan and assimilated Viennese Jew in fin-de-siecle Austria whose followers were largely East European Jews from traditional and observant backgrounds.

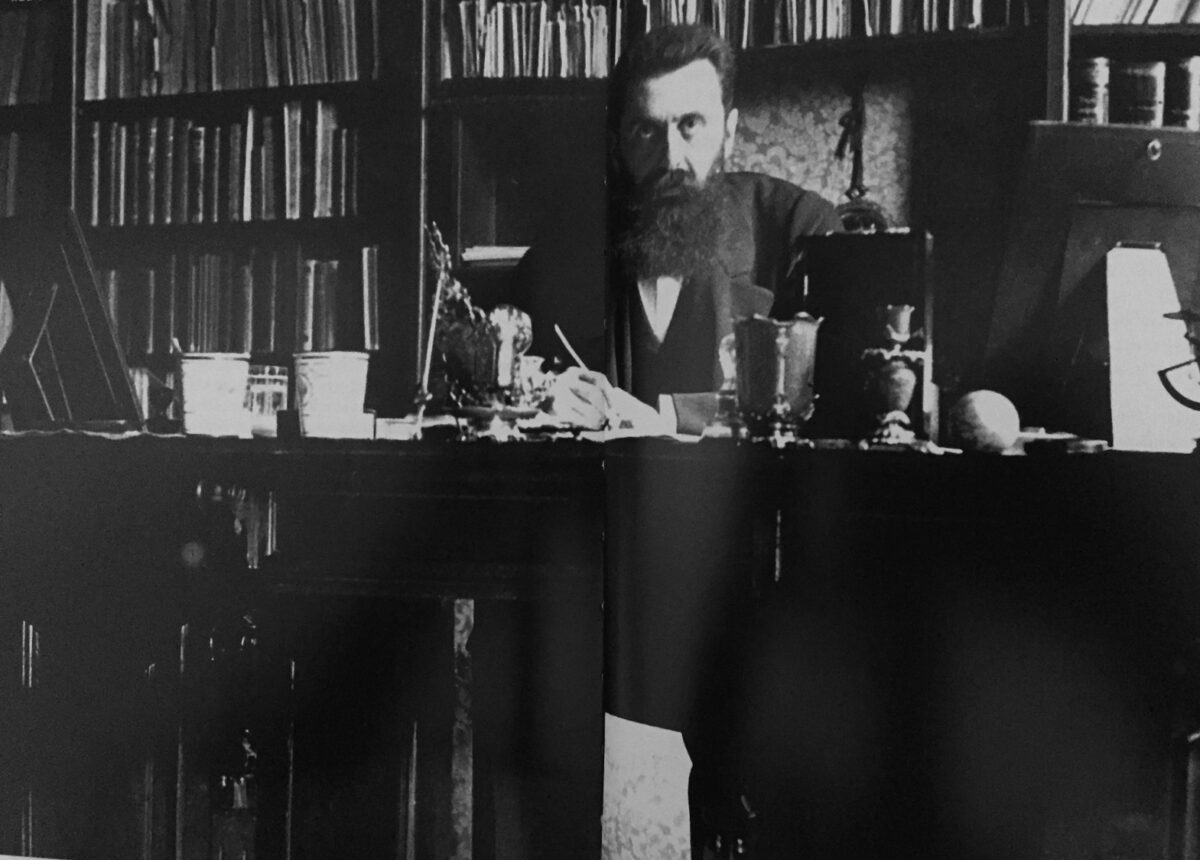

A lawyer by training and a playwright, novelist and journalist by avocation, he was a complex person. Aloof, guarded, self-absorbed, autocratic and plagued by bouts of depression and mood swings, he was a cool yet charismatic figure who inspired veneration and adulation from his acolytes.

But as Derek Penslar — a professor of Jewish history at Harvard University — observes in his magisterial work, Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader (Yale University Press), the majority of Jews greeted Herzl’s scheme with undisguised skepticism, suspicion and hostility. Most Orthodox Jews regarded it as blasphemous. Jewish socialists dismissed it as utopian. Assimilated Jews thought it was an absurd, embarrassing and counter-productive ideology that would confirm antisemitic notions that Jews were rootless and disloyal.

“Yet his message of Jewish national liberation, enunciated with mesmerizing oratory or couched in finely polished prose, struck a chord with many Jews,” Penslar writes.

“There was something captivating about him, which could scarcely be resisted,” the philosopher Martin Buber would write a decade after his passing.

Although antisemitism drove him into the arms of Zionism, “psychological anguish” paved his path to it. As Penslar puts it, “Herzl desperately needed a project to fill his life with meaning and keep the blackness of depression at bay. Zionism was that project.”

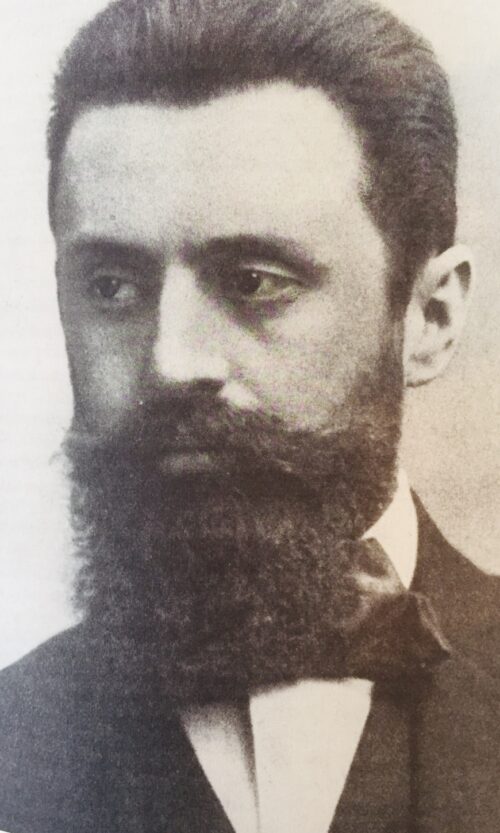

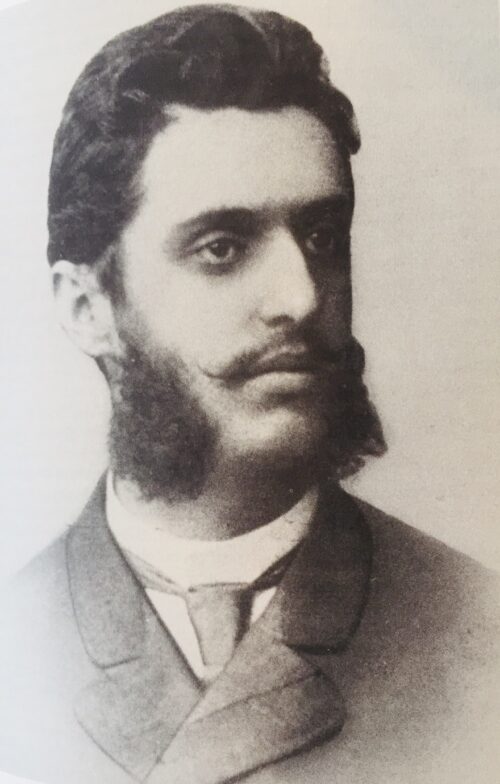

Herzl, born on May 2, 1860 in what is now Budapest, a major city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was the scion of a solidly middle-class family steeped in Germanic culture. Though he was an aspiring playwright and journalist, he studied law. Eager for social acceptance, he joined a fraternity, Albia, at the University of Vienna, but submitted his resignation after it turned virulently antisemitic.

Upon completing his doctorate, he worked as a state attorney, but finding the work tedious, he drifted into journalism. In his first job as a newspaperman, he was literary editor of a relatively minor publication in Vienna.

Like some Jews of his epoch, Herzl admired German nationalism and the Prussian nobility, which he identified with manliness, strength of character and discipline. His hero was Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian chancellor.

Claiming he lacked the ability to relate to women, Penslar says he frequented prostitutes. He contracted gonorrhea, but suffered no long-term symptoms after treatment. In 1889, he married Julie Naschauer, the daughter of a wealthy businessman who provided her with a handsome dowry. Their relationship was stormy. “I like her, but I cannot live with her,” he wrote in his diary.

Herzl was a mostly undistinguished playwright. His plays were mainly drawing-room comedies about love and marriage mocking human foibles. Yet a few, performed in Vienna and Prague, enjoyed considerable success. One, The New Ghetto, gleamed with intimations of Jewish nationalism.

“If Herzl had limited his writing to the theater, he would have disappeared into the footnotes of history,” says Penslar. “But he excelled at journalism, and it was in this field that he established an international reputation.”

Herzl wrote for the Jewish-owned, Viennese-based Die Neue Freie Press, one of the finest newspapers in Europe. Its resident correspondent in Paris from 1891 to 1895, he served as its literary editor from 1895 until 1904.

He was a master of the feuilleton, an observational essay set in lively, accessible language and peppered with gentle humor. By Penslar’s count, he wrote more than 300, a few of which dwelled on antisemitism, which intensified in Europe in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Herzl was in France when Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer, was falsely accused of espionage, stripped of his rank and imprisoned in a cause celebre that divided France. Its antisemitic overtones were familiar to Herzl, who had covered a story in which a Jewish lieutenant, Andre Cremieu-Foa, was killed in a duel after slurs had been hurled against the few Jewish officers in the French army.

Penslar believes that the election of the antisemitic mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, pushed him closer to examining the so-called Jewish Question in greater depth. Herzl now believed that antisemitism was no longer related to the hatred of Jews as killers or rejectors of Christ, but rather bound up with the historic Jewish connection to commerce and finance and the more recent entry of Jews into the professions.

In 1893, he called upon Austrian Jews to assimilate completely into Christian society by means of conversion, baptism and mixed marriage. Since Jews were still a persecuted people, he refrained from following his own advice, Penslar notes.

At that point, he had no interest in solving this problem through the reestablishment of the ancient Jewish homeland in Palestine. But Herzl gradually came around to the view that Jewish emigration from Europe was the only solution. He discussed this matter with Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a Jewish banker who had sponsored programs to resettle Russian Jews as farmers in Argentina.

He then wrote a lengthy document that formed the basis of The Jewish State, a 20,000-word pamphlet published in 1896 which explored the possibility of creating a modern and progressive homeland for Jews. Herzl’s friend, Max Nordau, was impressed. “This brochure assures you a lasting place among heroes,” he wrote.

Lev Pinsker, a founder of the Lovers of Zion, had written a remarkably similar work, Auto-Emancipation, 14 years earlier. Herzl claims he had never read it until the mid-1890s.

“One striking aspect of Herzl’s thoughts at this time is that he had no clear sense of where the Jewish state would be.” For a while, says Penslar, he appeared to favor Latin America, Cyprus, South Africa and North America. Only later did he focus on Palestine, an underdeveloped province of the Ottoman Empire.

When he finally focused his attention on Palestine, he had never heard of the word “Zionism,” which had been coined by the Galician Jew Nathan Birnbaum around 1890. Herzl adopted the Zionist label only after the publication of The Jewish State in 1896. “Herzl appreciated the strength and simplicity of the word, and he applied it to the Zionist Organization and the Zionist Congress, both of which he founded,” says Penslar.

Herzl’s activities did not endear him to all his fellow Zionists. Nahum Sokolow, the editor of a major Hebrew newspaper, warned that the Ottoman Empire would not tolerate an influx of Jews into Palestine. Asher Ginsberg, who wrote under the pen name of Ahad Ha’am, argued that what Jews needed most was a cultural renewal based on the Hebrew language, of which Herzl had only a minimal knowledge.

Middle and upper-midde class European Jews were generally disdainful of Zionism. As the Ottoman ambassador in London wrote in 1898, “they did not have the slightest intention to exchange their comfort, their habits, their contacts with all that is brilliant and elevated in the great capitals of Europe for a restricted and modest existence in Palestine.”

Much to Herzl’s chagrin, neither his bosses at Die Neue Freie Press nor his wife approved of his Zionism, which gave him “a reputation as a crackpot and brought him into close contact with men below his social station,” says Penslar.

Consumed though he was by his devotion to Zionism, which became the source of his identity, creative drive and will to live, Herzl continued to toil as a journalist. He not only required a livelihood, but perceived a direct link between journalism and statecraft. Herzl, whom Penslar describes as a “remarkable and singular” individual, poured immense efforts into “diplomatic Zionism,” courting high-ranking European and Ottoman officials in a bid to win them over to his cause.

Two hundred and fifty delegates, one-third of whom hailed from Eastern Europe, attended the first Zionist Congress in Basel. “There was a stark division between those attendees who wanted to pursue statehood and to declare that goal explicitly, and those who preferred … to speak of a homeland,” says Penslar. “Herzl, who wanted to maximize his freedom of negotiation with the Great Powers, tended toward declaratory minimalism.”

A compromise emerged in a resolution: “Zionism aims at establishing for the Jewish people a publicly and legally assured home in Palestine.”

In his diary, Herzl was more frank: “Were I to sum up the Basel Congress — which I shall guard against proclaiming publicly — it would be this: at Basel I founded the Jewish state. If I said this aloud today, I would be answered by universal laughter. Perhaps in five years and certainly in fifty everyone will know it.”

The New York Times, in its first mention of Herzl, sardonically observed, “Dr. Herzl’s scheme is entirely practical — whatever may be the case as to its practicability.” Tellingly, the commentary was placed near a news item about an unusual friendship between a rhinoceros and a cat!

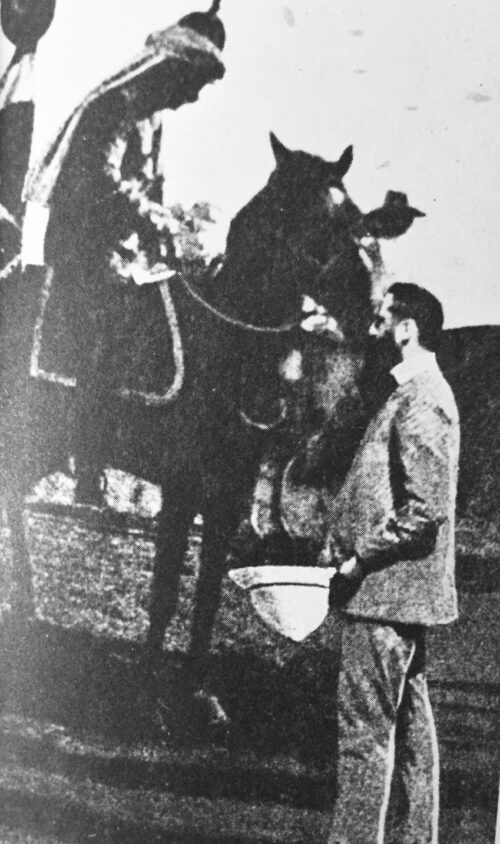

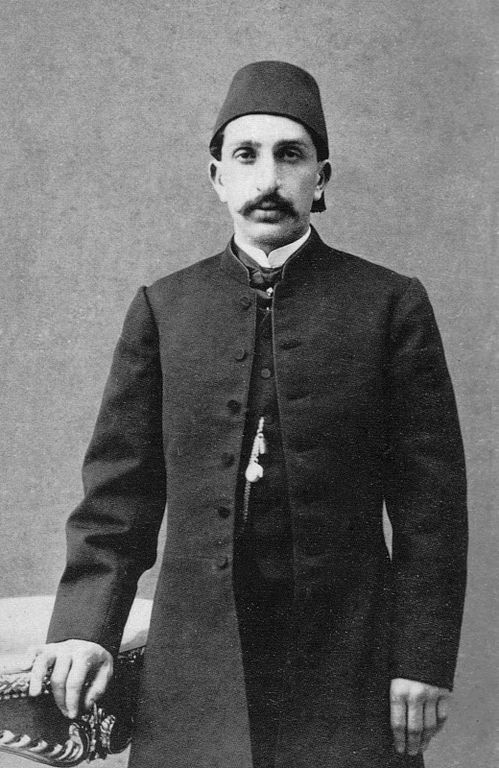

According to Penslar, Herzl’s Zionist career was at its zenith from 1898 to 1901, when he met, among others, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany in Palestine and the Ottoman sultan, Abdul Hamid II, in Constantinople. During these years, his closest associate was David Wolffsohn, a Lithuanian timber merchant who shared his Zionist dreams.

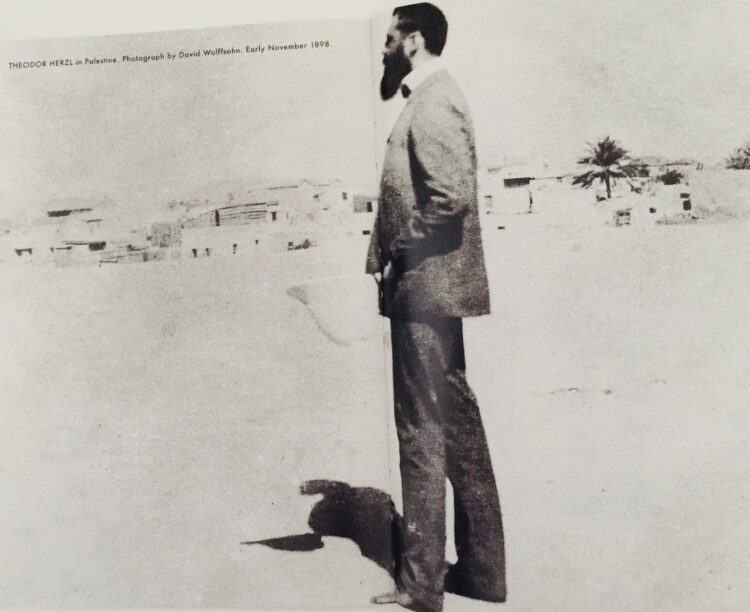

Wilhelm II, an arrogant person, essentially humored Herzl, dashing his hopes for German sponsorship of a Jewish homeland. Herzl went to Palestine, in his first and only trip there, for the express purpose of meeting the kaiser.

Herzl, who knew precious little about Palestine, spent 10 days there. “Before the visit, Palestine was an abstraction to him,” says Penslar. Herzl, having visited Jaffa, Jerusalem, Mikveh Israel and Rehovot, was generally disappointed by the backwardness, squalor and poverty of Palestine.

The sultan, whom Herzl described as “short, skinny, with a large hooked nose, a full dyed beard and a small tremulous voice,” did not comply with Herzl’s request either. He opposed any form of independence, much less sovereignty, for Jews in Palestine.

Undeterred by these rebuffs, Herzl carried on with his diplomacy. The British colonial secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, seemed open to Jewish colonization in the northern Sinai Peninsula, but soon slammed the door on it. Chamberlain eventually offered the Zionist movement 5,000 square miles of territory in the highlands of Uganda, in present-day Kenya, but the bulk of rank-and-file Zionists, being fixated on Palestine, rejected that proposal.

Herzl also conferred with Russian government officials like Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve and Finance Minister Sergei Witte, both of whom were eager to rid Russia of Jews. Much to his satisfaction, Herzl received a letter from Von Plehve supporting a Jewish state in Palestine, provided it could absorb sizeable numbers of Russian Jews.

“It is a great irony that the first endorsement of modern Jewish statehood by a Great Power came from Russia, a historic oppressor of the Jews,” says Penslar.

Herzl was far less successful in his demarche with the newly installed pope, Pius X, who brusquely told him that Jewish rule in Palestine was out of the question, but that the Roman Catholic Church was ready to baptize new Jewish settlers.

Herzl’s hectic schedule exacted a heavy toll on his health. From 1899 onward, he complained of palpitations, shortness of breath and an irregular pulse. In all likelihood, his symptoms were indicative of heart disease.

In his only novel, Altneuland, published 1902, the main character bore a striking resemblance to him: an outstanding Jewish journalist who becomes a Zionist and sails off to Palestine. Herzl envisaged Palestine as a peaceful, democratic and cooperative commonwealth held together by economic and cultural institutions. With the exception of one Arab character, Palestinians are missing from Altneuland.

“The novel’s epigraph, ‘if you will it, it is no fairy tale,’ became a watchword of the Zionist movement and the state of Israel,” says Penslar.

In all other respects, Altneuland is forgettable, he adds. “Few readers today would find literary value in the novel, which has a contrived plot, flat characters and wooden dialogue. Since Israel’s establishment, however, the novel has been a source of pride for Zionists, who see Israel as the fulfillment of Herzl’s vision of a tolerant and progressive society.”

Herzl fell ill with bronchitis on July 1, 1904 while vacationing in Switzerland, developed pneumonia two days later and died. His funeral in Vienna attracted thousands of mourners and onlookers.

In Penslar’s view, Herzl was “a symbol of Jewish pride, agency and striving for collective rebirth,” the “personification of Zionism.”

Sadly, his three children fared badly. Pauline, suffering from morphine addiction, died in France in 1930. Hans, circumcised at the age of 15, converted to Christianity and became an anti-Zionist. He committed suicide after Pauline’s death. Trude, who spent years in psychiatric hospitals, was deported to Theresienstadt, the Nazi camp near Prague, in 1942 and perished there.

Penslar’s biography, part of Yale University Press’ Jewish Lives series, penetrates deeply into the complexity of Herzl’s all-consuming mission. Although it is written by an academic, it reads like a first-rate piece of journalism, and is thus eminently accessible to readers of every taste.