Among Israel’s most ardent supporters in the United States are evangelical Christians, who, by one estimate, comprise something like a quarter of the American electorate. Socially and politically conservative, and profoundly steeped in biblical lore, they are staunch allies of Israel’s right-wing government.

Highly supportive of the settlement project in the West Bank and dismissive of Palestinian claims to statehood, they urged the former U.S. president, Donald Trump, to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and move the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Israeli filmmaker Maya Zinshtein examines the logical yet complex relationship between the evangelicals and Israel in her bracing documentary, ‘Til Kingdom Come, which will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival from February 27 to March 1. She and her cinematographer will appear in a Zoom question-and-answer session on Sunday, February 28 at 3 p.m.

Zinshtein travels far and wide to connect with the earnest and passionate members of this pious, God-fearing sect. Early in her 78-minute film, she turns up in the remote town of Middlesboro, Kentucky, deep in the scenic coal country of Appalachia, where pastor Boyd Bingham IV and his father administer to the faithful in a Baptist church.

From there, she proceeds to interview Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein, the founder and president of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, and his daughter, a Yael, the vice-president. Founded in the early 1980s, this organization has forged close ties with the evangelical community and its leadership on behalf of Israel.

Described in cosmic language by Yael as “a strategic partnership of God,” the fellowship runs over 100 charitable programs in support of Israelis below the poverty line, minorities, Holocaust survivors and security projects, and is subsidized by funds donated by evangelicals. According to Rabbi Eckstein, who died two years ago this month, they have funnelled $1.4 billion in contributions to Israel over the years.

As Zinshtein continues her trip, she makes stops in Texas, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C. and Israel. She talks to televangelist Pat Robertson, high-profile pastors like John Hagee, Johnnie Moore and Robert Jeffress, and a Jewish woman originally from the United States who lives in the West Bank settlement of Karnei Shomron.

Boyd Bingham IV, a gun fancier, is a dyed-in-the-wool Republican. “We are the people who brought Donald Trump to power,” he says. “He pushes our agenda.”

Addressing his congregants, the residents of one of the poorest American counties, he declares, “The Jewish nation, the Jews, are better than all of us.” Having given Christians the holy Bible, Jews are held in esteem and Israel is revered.

“There’s a spiritual obligation to Israel,” chimes in his father, adding that Israel’s foes are the enemies of God.

Rabbi Eckstein established relations with the evangelical community through Pat Robertson, an immensely popular television personality. Yael admits that some Israelis were initially skeptical about this relationship.

In evangelical prophecy, which is taken literally by true believers, two-thirds of the Jewish people in Israel will perish at the End of Days and the remainder will be forced to convert to Christianity. As Zinshtein strongly suggests, this is a very problematic scenario for Jews.

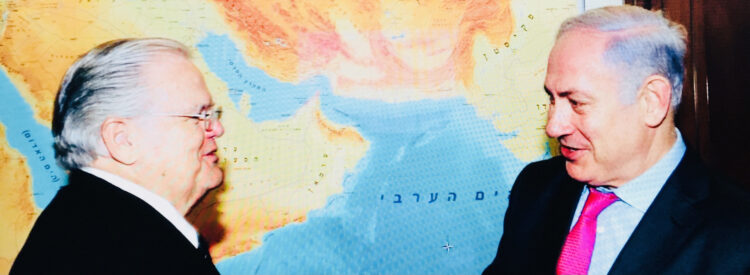

Whether such prophecy bothers Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his supporters has yet to be determined. But when Netanyahu meets Hagee, he says, “We have no better friend than you.”

Reverend Johnnie Moore, who was a member of Trump’s Evangelical Advisory Council, is a classic Christian Zionist. As he puts it, “We absolutely believe this land — Israel — was given by God to the people of Israel.”

Zinshtein was in Jerusalem on May 14, 2018, the day the U.S. embassy was officially transferred there. To the Palestinians, it was an act of war, causing an outburst of violence in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, but to Christian zealots like Hagee, Moore and Jeffress it was an important “signal in prophecy.”

While in Jerusalem, she chats with a Palestinian Arab Christian evangelical pastor who accuses his American counterparts of having failed to understand the dynamics of Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians. But he realizes they wield enormous clout. “We can’t underestimate their influence any more,” he says morosely.

A little later in the film, Boyd Bingham IV and this Palestinian pastor meet, but they’re poles apart on the basic issues. As far as the American is concerned, the Palestinian narrative is akin to “theological antisemitism” and “there is no such thing as a Palestinian.” Not surprisingly, he completely rejects the Palestinian claim to a sovereign homeland.

After her father’s death, Yael flies to the United States to meet Boyd Bingham IV on his home turf in Middlesboro, population 10,344. “The destiny of the Jewish people is the destiny of this church,” she says, speaking to his flock.

In Karnei Shomron, a Jewish settler underscores Israel’s links with the evangelical movement. “We have a lot in common,” she says. “Eighty percent of your Bible is my Bible.”

Dropping into a conference in Washington, D.C., Zinshtein watches evangelicals brandishing American and Israeli flags as they lobby against continued U.S. funding of the United Nations organization that materially assists Palestinian refugees in the Middle East.

Toward the close of the movie, Zinshtein attends a ceremony at the White House during which Trump and Netanyahu unveil the so-called Deal of the Century to resolve Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians.

To the Palestinian Authority, which boycotted the event, the one-sided U.S. proposal is dead on arrival because it calls for Israel’s annexation of 70 percent of the West Bank and all its settlements there. But to the evangelical elite in attendance, it is a blessing, a gift from the gods.

Zinshtein expertly captures the unwavering pro-Israel spirit of evangelical Christians, but she’s understandably wary of their extremism and ulterior motives.