He wants to be “here” and “there,” and therein lies the problem.

Romuald Jakub Weksler-Waszkinel can’t be Catholic and Jewish at the same time, as far as Israel is concerned.

Born to Polish Jewish parents in 1943, at the height of the Holocaust in Poland, he was adopted by a Catholic family when he was one week-old. This occurred shortly before his parents, Jakub and Batia, were murdered by the Nazis.

His was not an isolated case. In desperation, hundreds and perhaps thousands of Jews handed their children over to Catholics on the eve of their deportations.

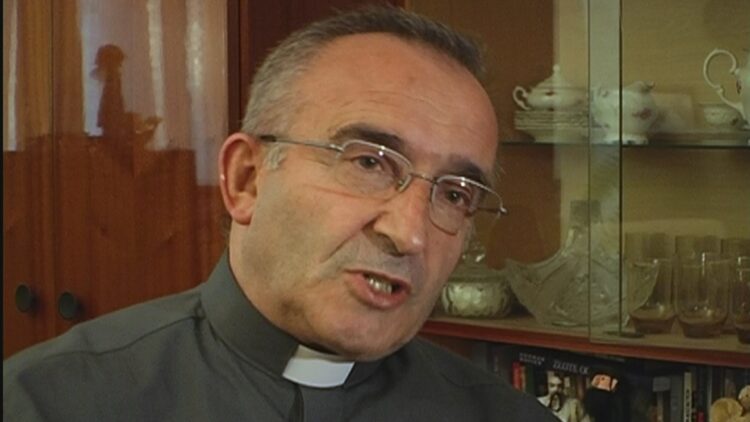

Raised as a Catholic, he was a 35 and an ordained priest for 12 years when his stepmother, Emilia, told him he was of Jewish descent. The discovery upended his life and prompted him to settle in Israel. But because he considers himself both Jewish and Catholic, the Israeli government has not yet granted him citizenship.

“He’s a living conflict,” says his friend, the chief rabbi of Poland, Michael Schudrich.

Weksler-Waszkinel is at the center of Ronit Krown Kertsner’s aptly titled documentary, Torn, which is now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform. Her sensitive and empathetic film delves into his tortured soul to a remarkable degree.

We first meet him at the Convent of the Ursuline Sisters in Lublin, where he lived and performed his duties as a priest before deciding to live in Israel.

He tells Kertsner that when his mother delivered him to the Waszkinels for safekeeping, she predicted he would grow up to be a priest. When, at the age of 17, he told his stepfather he sought to join the priesthood, he warned him he was setting himself up for a very difficult life.

In retrospect, his stepfather was right, he admits.

The Catholic church in Poland deems antisemitism sinful, but in practice it exists in the sermons delivered by some priests. Unwilling and unable to bear such hypocrisy, he decided to immigrate to Israel. By that point, he taught philosophy at the Catholic University in Lublin, a city in eastern Poland, and viewed himself as an emissary between Jews and the Catholic church.

On the eve of his departure to Israel, he claims his parents were Zionists and says he intends to learn Hebrew and immerse himself in Israeli society.

When he arrives in Israel, he’s met by Yanina Ecker, an Israeli of his generation who lived as a Catholic with a Christian family in Poland from the age of 10 to 17. Her parents, having survived the Holocaust, reclaimed her after World War II.

Weksler-Waszkinel wants the best of both worlds: to live on a religious kibbutz and attend Catholic services at a nearby church on Sundays.

At Kibbutz Sde Eliyahu, in the Beit Shean Valley, the director of the ulpan asks him point blank whether he’s Jewish or Catholic. It’s not an easy question for him to answer. And because he’s as attached to Judaism as he is to Catholicism, a monastery in Abu Ghosh, near Jerusalem, declines to accept him as a member.

Back at Sde Eliyahu, the kibbutz informs him he would be denied membership if he attends church. He understands its decision, but maintains his attachment to Jesus. “Christianity is a problem in Israel,” he muses.

The kibbutz, however, accepts him as a Hebrew student at its ulpan. Returning to Poland to wrap up his affairs, he has a tearful reunion with nuns in the convent before he goes back to Israel.

En route to Sde Eliyahu, he wonders what the future holds for him. At the kibbutz, he’s given a yarmulke to wear. Among his fellow students in the ulpan are five Chinese men who wish to convert to Judaism.

Weksler-Waszkinel is disappointed to learn he will be given temporary resident rather than new immigrant status in Israel. He accepts this with a sense of fatalism, realizing that his insistence on remaining true to two religious faiths is incompatible with Israel’s immigration policy.

The film, which was released about a decade ago, ends at this juncture. Today, Weksler-Waszkinel is a resident of Jerusalem and works in the archives of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum/memorial.

He still has not been granted Israeli citizenship.