The Toronto Jewish Film Festival, the finest cultural event in the city’s Jewish calendar, gets under way on May 1 and runs until May 11. As usual, there are films for every conceivable taste.

A sampler:

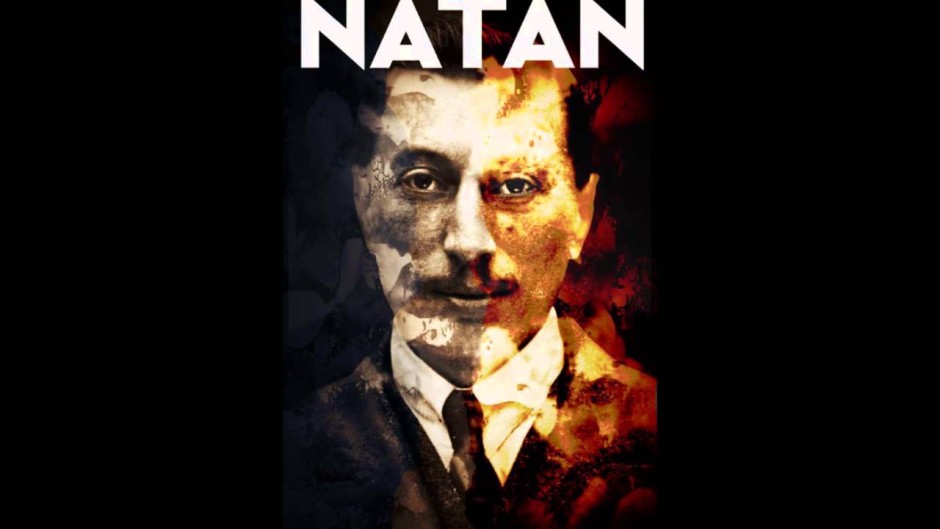

Bernard Natan was one of the founders of the modern film industry in France. A Rumanian Jew whose original name was Natan Tannenzapf, he was at the peak of his powers from the 1920s to the mid-1930s. Today, he’s a virtually forgotten figure. Natan, a riveting and chilling documentary directed by David Cairns and Paul Duane, brings him back to life on celluloid.

Born in 1886, he arrived in France in 1905. A chemist, he aspired to work in film, an ambition he succeeded in achieving. In 1910, after having formed the Rapid Film company, he was charged with distributing pornographic films and threatened with deportation. Bouncing back, he went to work for Pathe as a technician.

In a burst of patriotism following the outbreak of World War I, he enlisted in the French army. After the war, he returned to film, making his mark as a technical innovator. Natan, compared by some to Hollywood’s Cecil B. DeMille, bought Pathe’s exhibition unit. He made newsreels and scores of feature films, including Les Miserables and Wooden Crosses, a movie on the carnage of World War I.

Pathe-Natan, as it was called, went bankrupt in 1935, and Natan’s enemies pounced. Leftists excoriated him as a capitalist. Rightists attacked him as a foreigner, Jew and pornographer. Arrested in 1938, he was accused of fraud in connection with Pathe-Natan’s bankruptcy and sentenced to four years in prison.

In 1942, when France was under the sway of the fascist Vichy regime, Natan was denaturalized. Having lost his French citizenship, he became stateless.

Packed off to the Drancy transit camp, he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Sept. 24, 1942, where he was murdered in the following year. More than 70 years after his death, Natan is a non-entity, unknown even to film students.

Natan, tinged by tragedy and controversy, is a spellbinding documentary.

***

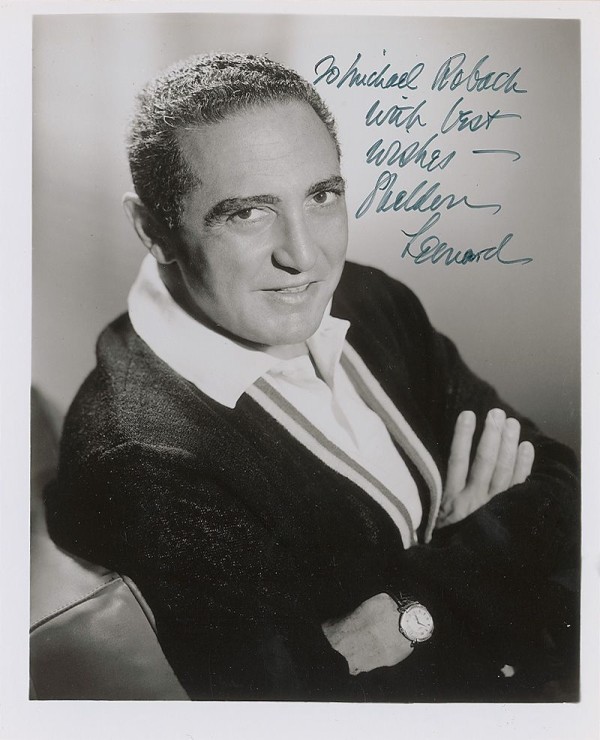

Sheldon Leonard (1907-1997) was an actor, script writer, director and producer, the brains behind some of the most successful sitcoms on American television — The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Danny Thomas Show and The Andy Griffith Show.

Allan Holzman’s biopic, Sheldon Leonard’s Wonderful Life, documents his career through interviews with Leonard and collaborators and actors such as Carl Reiner and Mary Tyler Moore.

In much of the film, Leonard discusses the origins of the TV shows that catapulted him to fame. It’s mildly interesting, but hardly the stuff of a first-rate documentary.

***

Naim Kattan lives in the Republic of Letters, as The Length of the Alphabet suggests. A journalist, novelist and cultural administrator, Kattan was born in Baghdad. After spending seven years in Paris, he settled in Montreal in 1954, knowing not a single person. Within a few years, he had amassed a circle of friends and established a reputation as a serious literary critic.

Joe Balass’ generally illuminating film traces his beginnings in Baghdad — a city divided into ethnic and religious quarters — and his interest in becoming a writer in Arabic. He left Iraq, bound for Paris, in 1947, just before the curtain fell on Iraq’s venerable Jewish community, a chapter The Length of the Alphabet completely neglects, to its detriment.

Kattan, who regarded French as the language of liberation, thrived in Paris, where he shed his provincialism and learned to love women. In the movie, he returns to his old haunts in the City of Light.

Intent on renewing himself, he immigrated to Canada. He experienced hardship and loneliness in Montreal, and was shocked to learn that French was inextricably associated with Roman Catholicism. His luck turned when the Canadian Jewish Congress hired him to produce a French-language bulletin aimed at a French Canadian readership, the first non-Catholic French publication in Quebec.

Championing dialogue with the French Canadian community, Kattan proved adept at building bridges to the Quebecois. He claims that French Canadian nationalism was not infused with the antisemitism that had marred it in the past.

Regrettably, Balass spends too little time on Kattan’s book about growing up Jewish in Iraq, Farewell, Babylon. But he focuses on his work at the Canada Council for the Arts, where he promoted Quebecois literature.

***

From Hollywood to Nuremberg, directed by Christian Delage, largely unfolds during World War II, when the U.S. government enlisted the assistance of Hollywood movie directors to churn out propaganda films to lift morale in the United States.

It profiles three directors, John Ford, George Stevens and Samuel Fuller, a young American soldier who would find his calling as a filmmaker.

Ford made Battle of Midway, a stirring documentary about a pivotal Pacific battle pitting the United States against Japan, while Stevens shot raw footage of two liberated Nazi concentration camps, Nordhausen and Dachau, where thousands died of maltreatment, disease and starvation.

Ford used graphic images of corpses and survivors in Dachau to make a powerful film, Nazi Concentration Camps, which was screened at the 1946 Nuremberg war crimes trial.

Fuller witnessed scenes of carnage in Falkenau, a Nazi camp in Czechoslovakia, and they left him numb. After the war, he became a movie director in Los Angeles.

From Hollywood to Nuremberg is episodic and disjointed. There is a vivid story here, but the script is weak and anemic.

***

Transit, an Israeli feature film by Hannah Espia, exposes the plight of Filipino migrant workers in Israel and the gulf between them and their Israeli-born children.

It concentrates on four Filipinos — Janet, whose Hebrew-speaking daughter, Yael, considers herself an Israeli rather than a Filipina, and Moises, whose five-year-old son, Joshua, is threatened by deportation.

Transit is set in the southern part of Tel Aviv, where the majority of migrant workers have settled. It’s a gritty area, far from the city’s affluent and sophisticated northern neighborhoods.

The film highlights the gap between Filipino workers and their Israeli-born and bred children and delineates the fear of deportation that haunts guest workers in Israel.

***

Ester Amrami’s Anywhere Else, set in Germany and Israel, turns on Noa (Neta Riskin), a temperamental 33-year-old Israeli linguist who’s caught between two countries and two worlds, Israel and Germany.

Noa, a post graduate student in Berlin compiling a dictionary of odd words, is disappointed to learn that her MA thesis does not pass muster. As she reels from this news, her German boyfriend. a musician named Jorg (Golo Euler), informs her he is going to Stuttgart for an audition. With nothing better to do, she boards a flight to Israel.

Israel is the antithesis of Germany — warm and sunny and bright. Beyond the fine weather, Israel represents family warmth. Her parents and grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, are glad to see her again. Noa feels good to be back in Israel, yet she also feels disconnected from the country.

Jorg surprises Noa by showing up in Israel. Rachel (Hana Laslo), Noa’s mother, invites Jorg to stay with them, even though she is displeased that her daughter’s boyfriend is a German. Noa extends her trip to Israel after her beloved grandmother is hospitalized. A viewer may suspect she has ulterior motives for postponing her return to Germany.

The film is discerning about the fraught nature of German-Jewish relations. This theme surfaces at an awkward dinner table conversation and at ceremonies marking Independence Day celebrations and Holocaust Remembrance Day. Further tensions emerge as Noa quarrels with Rachel and her married sister. Things come to a head when Jorg tells Noa that their relationship isn’t working.

Anywhere Else coaxes fine performances from its cast and makes telling points about the importance of family and country and the fragility of human relations.