This year’s Toronto Jewish Festival, rebranded as the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation, runs from May 4-14. The five films reviewed here are eclectic. They’re about a Polish village which once had a substantial Jewish population, an Israeli couple whose marriage grows more stale by the year, an ultra-Orthodox woman who runs for a seat in the Israeli Knesset, the unlikely relationship between two very different people in Britain, and three Israeli soldiers who get left behind on a military base when Israel withdraws from southern Lebanon.

The village of Ivansk, in southern Poland, is bereft of Jews today, but before World War II most of its residents were Jewish. During the Nazi occupation, they were deported to extermination camps, never to return. Not a trace of their pre-war presence remains. Even the Jewish cemetery was desecrated.

Scandal in Ivansk (May 9 & May 11) turns on the efforts of a group of American Jews, led by physician Norton Taichman, to restore the cemetery and memorialize the birthplace of their ancestors. Co-director David Blumenfeld has a personal interest in the project. His grandfather was born in Ivansk. Much to his disappointment, he learns that the village erected a monument in honor of Poles killed by Germans, but neglected to build one for Jews.

Blumenfeld and co-director Ami Drozd assume that the culprits who vandalized the cemetery probably will never be found. But as they dig deeper, they discover that local Poles were the perpetrators. Poles in Ivansk used broken headstones as construction materials and removed stone fragments to build a park. Still other Poles “stored” headstones on their properties in the hope of selling them to Jews one day. In the final indignity, Poles excavated cowhide Torah scrolls, which had been buried by Jews to protect them from harm, and used them in the manufacture of shoes.

This somber film is ultimately about memory. Local Poles of a certain age speak objectively about their former Jewish neighbours, recalling that they owned most of the shops in the village. Still others denounce fellow Poles who grabbed Jewish-owned land and possessions after their proprietors had been deported. Resurrecting an antisemitic myth, an elderly woman jokingly claims that Jewish bakers added a drop of human blood to their matzoh.

In the main, Scandal in Ivansk charts the efforts of the American Jews to clean and rededicate the neglected cemetery. A controversy erupts at this juncture. Carved into the dedication stone of the Jewish monument in the cemetery is the explosive word collaborator, which refers to Poles who cooperated with the Nazis. Local residents are outraged, insisting that Poles did not collaborate with the Germans. Jan Gross and Jan Grabowski, two Polish historians who live abroad and have been vilified by right-wing Polish nationalists, believe that collaboration is indeed the right word.

Scandal in Ivansk raises difficult issues in the fraught landscape of Polish-Jewish relations.

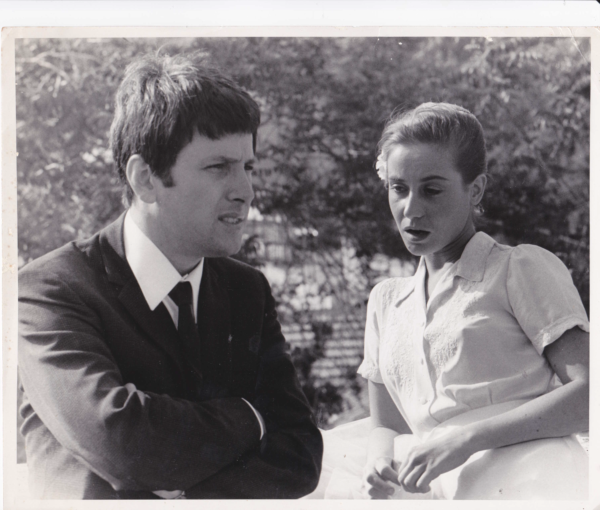

Adapted from Amos Oz’s novel, Dan Wolman’s feature-length movie, My Michael (May 12), is drenched in sadness. Released in 1976, it stars Efrat Lavie and Oded Kotler as an Israeli couple who struggle with an increasingly dysfunctional marriage.

Michael (Kotler) and Hanna (Lavie) are students when they encounter each other in western Jerusalem in 1950. He’s studying geology. She’s completing a degree in Hebrew literature and teaching in a kindergarten. Both are serious and reserved in demeanor.

When she plants a quick kiss on his cheek one night at the end of their date, he says, “I want to marry you.” These are not mere words. Michael knows what he wants and articulates his desires straightforwardly.

Their respective mothers think they’re being hasty. Michael’s domineering mother asks Hanna to wait at least a year. She’s concerned that marriage may interfere with her dear son’s studies and ruin his career. Hanna’s mother is critical, too, wondering why she’d marry someone she hardly knows.

When Hanna happily announces her pregnancy, Michael seems stunned. His stoic reaction disappoints Hanna. When Michael’s intrusive mother urges her to get an abortion, he looks on silently, implicitly siding with his mother.

Having realized she and Michael are emotionally incompatible, she has erotic dreams about two Arab men ravishing her. The reference to Arabs is not surprising. During her childhood, two of her best friends were Arab boys. Clearly disillusioned with Michael, a bookworm who spends his days studying for an advanced degree, she compares herself and him to strangers inhabiting the same space. In their case, it’s a cramped apartment in a decrepit neighbourhood.

Hanna gives birth to a boy, naming him Yair, but she remains depressed. Six years pass and the Sinai war breaks out. Michael is called up for reserve duty, and when he suddenly returns, their reunion is formal. Frustrated by his taciturn and regimented manner, she implores him to be less restrained.

As they continue to drift apart, Michael grows close to a woman, a fellow student, while Hanna implicitly flirts with a teen age boy she’s tutoring.

My Michael, ably directed by Wolman, is a finely-tuned portrait of a troubled relationship. Lavie and Kotler turn in excellent performances in this elegiac film.

Ruth Colian is a fighter. That’s clear from the first moment of Measures of Merit (May 8 & May 10), a thoughtful documentary directed by Irit Dekel.

An ultra-Orthodox Israeli who rejects conventional thinking, she was a unique candidate in the 2015 general election, running for a seat in the Knesset under the banner of the newly-founded Women’s Merit Party. What makes Colian different in haredi circles is her steadfast belief that the sexes are equal.

Working with very limited financial resources, Colian was up against it when she announced her intention to enter politics, a man’s game in her extremely conservative and cloistered community. Aryeh Deri, the leader of the ultra-Orthodox Shas Party, expressed a common view when he declared that women like her should know their place and refrain from questioning rabbinical authority.

As Colian campaigned, haredi men claimed that she was violating sacred traditions and family values, and that she belonged at home rather than in parliament. She persisted. “The world is too masculine,” she replied. “Take us into account.”

Her plea fell on deaf ears. Haredi publications refused to publish her campaign ads. Haredim on the streets brushed her off. Her husband, Moshe, was non-committal, but praised her compassionate outlook.

Although Colian bumped up against a glass ceiling, she’s convinced that the battle for full equality is far from finished. She may be right, but this will be a long war.

They’re the odd couple.

In Love is Thicker Than Water (May 8 & May 11), directed by Ate De Jong and Emily Harris, Arthur Davies and Vita Berliner, two young people from vastly different backgrounds, meet at a dance and fall in love. But can they overcome their religious and class differences? That’s the $64,000 question in this mildly entertaining British film.

Consider the obstacles that lie in their path. Arthur (Johnny Flynn), an aspiring economist, is a bike courier from a small town in Wales. His father was a steel worker until his retirement. Vida Berliner (Lydia Wilson), a cello student from London, is Jewish. Her father is a physician. Her grandparents are Holocaust survivors.

So what do they see in each other? Can they make a life together? These questions arise from almost the outset. They clearly enjoy each other’s company and both like sex. But is that enough? Not quite. They quarrel when Arthur’s black step-brother refers to Vida as a “Jew girl.” They reconcile and let bygones be bygones, prompting Vida to describe Arthur as her “knight in shining armor,” her King Arthur.

When their parents finally meet, the encounter is awkward. Vida’s mother gets it right when she says, “If you marry this guy, we have to marry his family.”

Their mutual ardor is tested with deaths in their respective families. Can Arthur and Vida cope during this grieving period? Do they have enough in common to move forward? Arthur and Vida are an attractive couple, and Flynn and Wilson portray them convincingly enough. But their rollercoaster friendship is only skin deep and not really worthy of a feature-length movie.

Israel withdrew unilaterally from southern Lebanon in May 2000, ending an 18-year presence in its self-declared security zone. The Last Band in Lebanon (May 6), a slapstick comedy directed by Ben Bachar and Itzik Krichell, derives its inspiration from that event.

As Israeli soldiers cross back into Israel, glad to have survived, three soldiers are left behind enemy lines to fend for themselves. They’re Shlomi (Ofer Hayoun), Kobi (Ofer Shecter) and Assaf (Ori Laizerouvich), members of an army band who entertained the troops. At first, they don’t realize they’re marooned in Lebanon, but as this understanding seeps into their collective consciousness, they panic.

The arrival of a small Hezbollah force in their camp heightens their fears. Terrified that their army uniforms will expose them as Israelis, they strip down to their underpants and head for the border, 20 kilometres away. They run into a group of friendly Lebanese soldiers from the now-disbanded South Lebanon Army, but they’re not certain they can be trusted. And so they press on toward Israel.

The scenes shift between Lebanon and Israel as important blanks in the story line are gradually filled in. Viewers are left with the impression that Israeli and Lebanese cigarette and drug smugglers may have earned enormous profits as Israel and Hezbollah fought it out in Lebanon.

The humor, such as it is, is heavy-handed and infantile. There is not subtle or reflective moment in this forgettable film.