This year’s edition of the Toronto Jewish Film Festival runs from May 1-11 and features a wide assortment of feature-length movies, shorts and documentaries from around the world.

A sampler:

Lucia Puenzo’s Argentinian feature film, The German Doctor, focuses on Josef Mengele, the Nazi war criminal who found a haven in South America after the war. Like some Nazis, Mengele settled in Argentina, which turned a blind eye to war criminals and had a fairly large German population.

The movie starts in Patagonia — a wild region of mountains and forests — in 1960. A man with a German accent who calls himself Helmut Gregor (Alex Brendemuhl) asks a couple with children for directions to Bariloche, a resort town in the foothills of the Andes. He follows them through driving rain until they reach an inn. The following day, they resume the journey, only to part ways a little later.

Showing up in Bariloche, Gregor runs into the couple again. Eva (Natalia Oreiro) is an ethnic German, and her husband, Enzo (Diego Peretti), is a doll maker of Italian origin. They hope to reopen their hotel soon. In the meantime, they agree to rent Gregor a room.

Ethnic Germans in Bariloche look up to and respect Gregor, an imposing, no-nonsense person. They know he’s hiding behind a false identity and is really Mengele. After a newspaper reports that Israeli agents have launched a manhunt for Mengele, the suspicions of a local photographer are aroused. She suspects that Gregor is Mengele.

As tensions build, Gregor offers growth hormone treatment to Eva’s daughter, Lilith (Florencia Bado), who’s too short for her age. Eva keeps the news from Enzo, who opposes the treatment. To mollify Enzo, Gregor devises a profitable method of mass producing porcelain dolls he can sell.

After Israeli agents capture Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires, Gregor’s allies scramble to find a safe haven for him somewhere else in South America.

The German Doctor brims with suspense and fear.

***

Ilan Duran Cohen’s The Jewish Cardinal is a workmanlike biopic about Jean-Marie Lustiger, the first known Jew to become a prince of the Roman Catholic church. This engaging French film covers the most formative years of his life, from his appointment as bishop of Orleans, where he was baptized in the early 1940s, to his ascension as a cardinal.

Born in Paris in 1926, Lustiger was the son of Polish Jews who immigrated to France after World War I. During the Nazi occupation of France, he was hidden by a Catholic family whose piety rubbed off on him. His father, Charles, survived, but his mother, Gisele, was murdered in Auschwitz.

The film starts in 1979 as a priest on a moped heads down a city street in France. It’s Lustiger, played with aplomb by Laurent Lucas. He dreams of working in Jerusalem, but his superior has other plans for him. He informs him he’s been given a promotion. He’s now bishop of Orleans, a job he gladly accepts. Lustiger’s father is less than thrilled, calling his son a “shameful Jew.” Nonetheless, he invites his father to his consecration.

As portrayed in the film, Lustiger is torn between Judaism and Christianity. He’s not ashamed of his Jewishness, but he considers it a private matter, as he tells a reporter delving into his life

The scene shifts to the Vatican, where the new Polish-born pope, John Paul II (Aurelien Recoing), greets Lustiger warmly. In reply to Lustiger’s pointed question, the pope insists he did not appoint him bishop because of his status as a convert. It’s clear from their cordial exchanges and body language that John Paul II likes and admires Lustiger and that they’re on the same wave length.

As the film races ahead, Lustiger is appointed archbishop of Paris, a position that enables him to meet leading members of the Jewish community. The outgoing chief rabbi of France urges him to stop proclaiming he’s both Jewish and Catholic, but he refuses. The incoming chief rabbi, however, looks beyond this issue and establishes a rapport with Lustiger.

Portrayed as a man with a volcanic temper, Lustiger reaches the apex of his career in 1983, when the pope names him both a cardinal and his personal advisor. Visiting Auschwitz, he’s outraged to discover that the Jewish pavilion is closed and that knowledge of the Holocaust in Poland is skin deep. Flashbacks of Lustiger’s boyhood appear and reappear, but they’re fragmentary.

Auschwitz figures prominently in the film yet again when Lustiger throws himself into the controversy over the presence of a Carmelite convent there. This incident engenders tension between Lustiger and the pope.

The Jewish Cardinal treats all these issues with the seriousness they deserve, but never ignores the human drama behind them.

***

The Holocaust is a theme that has crept into Polish films with increasing frequency since the end of communism in Poland. In Hiding, set in the city of Radom in 1944 and 1945 and directed by Jan Kidawa-Blonski, is one of the latest in this genre.

Janka (Magdalena Boczarska), a cellist, is surprised to find a guest in her father’s house. Her name is Ester (Julia Pogrebinska), she’s Jewish and she’s hiding in their basement. Ester is his friend’s daughter, and she’ll be staying with them for a while. Decency requires that they extend a helping hand to Ester, a dark-haired dancer. Janka, fearing that Ester will expose them to punishment by the Nazis, protests.

After Janka’s father is arrested by the Germans, the two women gravitate toward each other sexually, even as Janka carries on an affair with a Polish lover. When an intruder bursts into the house, threatening to blackmail Janka, she and Ester resort to harsh measures.

Their bond is so close and intimate that when the war ends, Janka conspires to keep Ester in the dark about its outcome. Janka wants Ester completely to herself.

The film is claustrophobic, erotic (not the kind you’d find on https://www.tubev.sex/?hl=ja) and somber.

***

Like In Hiding, The Pin takes place in Nazi-occupied Europe and, uniquely, unfolds almost entirely in Yiddish.

By chance, two young Jews in Lithuania who’ve lost their families in German massacres meet in a barn in the countryside. They remain nameless throughout Naomi Jayne’s bleak and bitter film. She (Milda Gecaite) offers him (Grisha Pasternak) a fresh apple after he fails to find food in the forest. He offers to take her to the border, where freedom may beckon.

They talk, kiss and make love in the hay. Their love-making is robotic, bereft of passion.

The film dips into the surreal as it flashes back to a funeral home, where a guard watches over a freshly-arrived corpse. The connection between now and then seems palpable.

A German soldier with a swastika armband searches the barn, but doesn’t find the pair. After he leaves, they swear allegiance to each other. It’s virtually the only tender moment in The Pin.

They fornicate again, but this time there is passion and partial nudity. Trouble looms yet again when another intruder, a boy with a gun, appears. Later, they wait for a freight train that may take them to safety.

The Pin is atmospheric, full of long, soulful silences, the howl of the wind, the patter of rain and the growl of thunder.

***

Pawel Lozinski’s documentary, Birthplace, is wrenching and sometimes even hard to watch. Dredging up the profound pain and betrayal of the Holocaust, it unfolds in Poland as a former Polish Jew, now an American citizen, returns to the village where a double tragedy occurred.

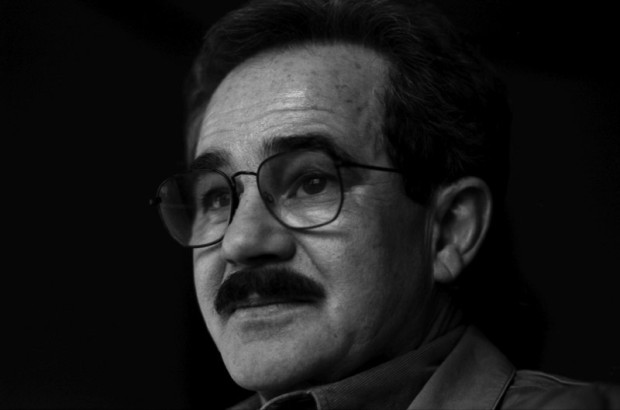

The protagonist, Henryk Grynberg, is a writer and poet who left Poland in 1967, just before the Polish government launched an antisemitic campaign under the guise of anti-Zionism that resulted in the emigration of much of Poland’s Jewish population.

On a grey winter day, he arrives in Radoszyna, hoping to ferret out information about his family. Grynberg, born in Warsaw in 1936, was a boy when he and his younger brother and parents reached the village. Presumably, his father and mother believed they might survive in Radoszyna, a speck on the map far from the prying eyes of the Germans.

The film divulges its story in dribs and drabs, building suspense as it proceeds.

Grynberg introduces himself to a farmer, and he remembers when Jews traded with local peasants. Next, he talks to two Poles about his mother and a pre-war wedding during which a delicious cake was served.

A fourth villager, a rough-hewn person who makes a sharp distinction between Poles and Jews, claims he gave his mother food. Still another Pole shows Grynberg a dugout in the earth where Jews hid.

All the Poles he encounters remember his family as if they had met yesterday, yet they seem emotionally distant.

A jarring note is struck when a farmer accuses local Poles of having murdered Jews. These Poles, he says, were worse than the Germans. It’s at this point that the film reaches its inner core.

Grynberg, a serious man who never smiles, asks his Polish interlocutors whether they know what happened to his brother, who was 18 months old at the time. After a few conversations, he finally learns the bitter truth, but remains remarkably stoic.

The film grows still more intense as Grynberg asks villagers what became of his father, Abram. They give him incomplete answers, whetting his curiosity. They say they were afraid of their neighbors. They claim they helped Jews and condemn the “bastards” who betrayed them. They say that Poles jeopardized their lives to assist Jews.

These comments lead Grynberg closer and closer to the nub of the horrific events that unfolded in Radoszyna during these terrible times.

Box office info.

Full festival film schedule available — online at tjff.com.

TJFF Ticket Pricing:

$13.00 – Single Tickets

$8.00 – Matinee Screenings

$9 – Seniors/ Students

$8.00 – Horror/ Fantasy Series Films

$20.00 – Opening Night

Main Number to Call is Festival Box Office: 416-324-9121

Advance Box Offices:

ORDER TICKETS ONLINE FROM TJFF.COM.

In Person – Toronto Jewish Film Festival Box Office (basement level) — April 17 – April 30, 19 Madison Ave., Sunday – Friday 12 p.m. – 6p.m. No wheelchair access — please call 416-324-9121 for assistance by phone.