This year’s edition of the Toronto Jewish Film Festival runs from May 1-11 and has a roster of eclectic movies from different countries.

A sampler:

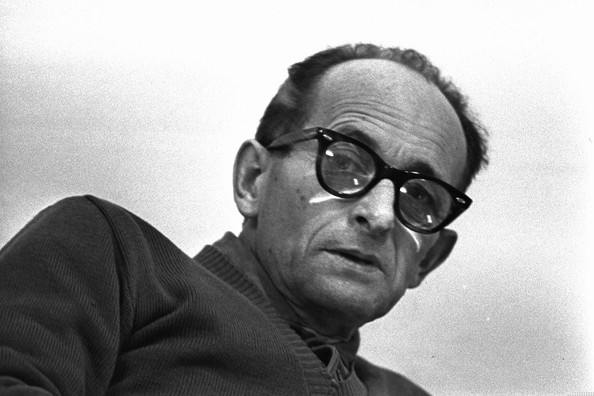

Yoav Halevy, in Bureau 06, profiles the Israeli organization that gathered the evidence and the witnesses in preparation for the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, who supervized the deportation of some 400,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz.

Fourteen investigators focused on different facets of Eichmann’s crimes, and the work consumed them. “We were totally immersed,” recalls one of them.

Meanwhile, Eichmann was interrogated by a member of the team, Avner Less, who was born in Berlin and immigrated to Palestine in 1938. Less was disappointed by Eichmann, considering him remarkably bland and ordinary. Instead of feeling hatred toward Eichmann, he pitied him. Nonetheless, Less was convinced he was a “sworn Nazi.”

Respecting Less as an equal, he unburdened himself of incriminating information. Recalling an important conversation with SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler, Eichmann said he was told that Hitler had ordered the extermination of European Jewry. Eichmann admitted he did not expect such a “violent solution” to the Jewish problem.

As this informative film moves forward, we learn that some potential witnesses were disqualified because their testimony could not be corroborated, that the investigators suffered from psychological stress and that many Israelis were ignorant about the Holocaust.

***

Cultural dissonance is at the core of Ali Adwan’s drama, Arabani.

Yusuf (Eyad Sheety), an Israeli Druze, returns to his ancestral village in the Galilee after a long absence and a divorce from his Jewish wife. He’s accompanied by his his two teen-aged children, Smadar (Daniella Niddam) and Eli (Tom Kelrich), who are Israeli culturally, linguistically and sartorially. In a traditional and isolated village like this, they are like fish out of water. Nonetheless, Yusuf has come back with the intention of staying. It’s hard to understand why he thinks his children will be able to adapt themselves to such an alien milieu.

Yusuf’s mother, a widow, greets him with a slap across the face, in an unmistakable sign that his presence is not appreciated. Nor is she happy that Smadar wears tight shorts and Eli dislikes “Arab” food. In short, she looks askance at her son’s children.

The reception Yusuf receives outside his mother’s house is just as hostile. Yusuf’s old flame rebuffs him and village elders shun him. His mother is ostracized by the temple, derogatory graffiti is spray painted on her wall and a rock is thrown through her window.

In an attempt to calm tensions, Sami (Mahmoud Abu Jazi), Yusuf’s brother, invites the village elders for a talk. Informing him that his children have behaved improperly (Eli was seen smoking and wrapped in the folds of an Israeli flag, while Smadar offended villagers by dressing indecently), they urge him to leave. The following day, the village sheikh tells Yusuf he “ruined” his life by marrying a Jewish woman.

Adwan’s film, strong yet subtle, is an object lesson in ethnocentrism. The Druze are manifestly loyal to the Jewish state, but Jews and Druze live in completely different worlds and hew to different social codes. Arabani hammers home that point forcefully.

***

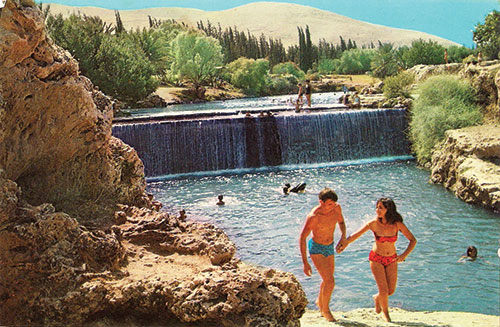

Sachne, or Gan Hashlosha, is an Israeli natural wonder to behold, an idyllic beauty spot in the Galilee lying sedately in the shadow of Mount Gilboa. Consisting of pools and rolling lawns shaded by stately palm trees, it’s one of Israel’s most popular nature reserves and the subject of an aptly titled documentary, Garden of Eden.

The film showcases Sachne in summer, autumn, winter and spring. Summer is the high season, but people keeping coming all the year round. Last year, Sache attracted 400,000 visitors. The weather changes with the seasons, but the water temperature of the pools remains the same, a toasty 28 degrees, since they’re fed by warm springs.

The implicit message of Garden of Eden is that water soothes the soul. And there are souls to be soothed, judging by the Israelis, Jews and Arabs, who frequent the park.

We meet a man whose still bears the emotional scars of his marriage breakup. We meet an Israeli Arab who finds life in Israel exhausting and wants to immigrate to Canada. We meet another Israeli Arab who passed up the opportunity to marry a fine Russian woman and now regrets his decision. We meet a German Jew who fled Nazi Germany. We meet a half-Jewish Ukrainian immigrant who enrolled in the Israeli army. We meet a veteran of the Yom Kippur War who lost a brother and a cousin in that conflict.

We also meet two very distinctive groups — Christian pilgrims from Brazil whose members pray for peace and Israel’s well-being and Orthodox men and women who loosen up as they enjoy the amenities.

In passing, the camera pans on, among others, sun bathers, swimmers and a newly-married couple posing for theatrical photographs.

A delicate issue is raised when the park ranger debunks the myth that 85 percent of Sachne’s visitors are Arabs, a reason some Israelis avoid Sachne. In fact, 15 percent of its visitors are Arabs. The issue, sadly, underscores the nature of Jewish-Arab relations in Israel today.

***

Ayelet Dekel’s intriguing movie, The Israeli Code, is s snapshot of cultural values and attitudes in contemporary Israel.

Israelis, their patriotism notwithstanding, realize that Jews in the Diaspora are safer. After all, wars and terrorism impinge on the lives of Israelis, and bomb shelters dot the urban and rural landscape.

Dekel, in broad brush strokes, paints a portrait of Israelis. They tend to be pushy when boarding buses. They leave trash in public places. They hate being taken for suckers. They love their flag, the Magen David. They use cell phones obsessively. They share woes and joys with strangers. They are very opinionated. They follow current events religiously.

These are generalizations, of course, but Dekel’s observations are nonetheless acute.

***

Jeffery Bonna’s Oro Macht Frei focuses on the darkest period to which the Jewish community in Rome, the oldest continuing one in the Diaspora, was subjected. This era stretched from 1938, when the first antisemitic laws in Italy were enacted, to 1943, when Germany terrorized and rounded up Jews in a prelude to their deportation to Nazi extermination camps in Poland.

Roman Jews were ghettoized for more than 400 years, reduced to lending money and selling old clothes. But after Italy’s unification in the 19th century, the ghetto was abolished and Jews were integrated into the fabric of Italian society. By the dawn of the 20th century, they identified themselves as Italians with a different religion.

Imagine, then, how shocked they must have been when Benito Mussolini, the fascist leader, relegated them to second-class citizenship with the passage of racial laws in 1938 and 1939. “We never expected something like that,” says a woman who lived through this horrendous epoch.

According to historian Alexander Stille, an expert in Italian history, the racial laws were passed to “harmonize” Italy’s relations with Nazi Germany.

Jews rejoiced when Mussolini was deposed in 1943, only to fall into the depths of despair when Germany invaded Italy to reinstate him. Within days, Jews in northern Italy were deported to Poland. The terror reached Rome in mid-October, when SS thugs raided the headquarters of the Jewish community and demanded a ransom of 50 kilos of gold. It was paid, but Nazi thuggery prompted Jewish leaders to go into hiding, leaving ordinary Jewish citizens totally exposed. In house to house raids, the Nazis arrested more than 1,000 Jews. Still more went into hiding in monasteries and convents.

Pope Pius XII requested a halt to the arrests, but did not speak out in protest, fearing he would do more harm than good and imperil Catholics in Germany.

Roman Jews celebrated when the U.S. army liberated Rome on June 4, 1944. Jews in Nazi-occupied Italy, however, had to endure many more months of hardship and discrimination. When the war ended, 20 percent of Italian Jews had been murdered.

Jews who witnessed these cataclysmic events recall them in vivid stories that speak volumes. Oro Macht Frei brings it all back.

***

Pepe Danquart’s Run Boy Run is based on the real-life adventures of Srulik Fridman, a Jewish boy who survived the Holocaust in Poland by living on his wits. Fridman, smuggled out of the Warsaw ghetto in 1942, got by with a little help from decent Poles, but mostly, he relied on his cunning and strength of spirit to survive.

As this evocative film opens, Fridman, convincingly portrayed by the twins Andrzej and Kamil Tkacz, steals a farmer’s jacket in the dead of winter. The farmer beats him, but Srulik escapes into the dense forest, shivering in the cold as he stops to rest. This is obviously a boy who can fend for himself.

In a flashback taking us back six months, Srulik hooks up with a bunch of Jewish kids who survive by stealing food from farmer’s fields. A German patrol scatters them in all directions, leaving a shaken and crying Srulik all alone in the world. A sympathetic Polish woman whose husband and two sons have joined the partisans offers him shelter for a while and teaches him how to be a Catholic Pole. Subsequently, he changes his name to Jurek Staniak and pretends to be a Christian.

As the film proceeds, he stays with yet more Polish families. He’s arrested after a Polish couple turn him in to the Germans, but manages to escape. He loses part of an arm in a thresher, and a kind Polish doctor attends to his wounds after one of his antisemitic colleagues refuses to provide treatment. From that point onward, Srulik never remains in one place too long, fearing he will be betrayed.

Unfolding in Polish, German, Yiddish and Hebrew, the film depicts Poles realistically. A few are steeped in antisemitism. Most are indifferent. Still others are guided by humanism.

The cinematography is striking. Rural Poland, its fields, rivers, forest glades and farms, is beautifully evoked. But this is a harsh and unforgiving landscape if you’re a Jewish boy dodging death.

Box office information

Full festival film schedule available online at tjff.com.

TJFF Ticket Pricing:

$13.00 – Single Tickets

$8.00 – Matinee Screenings

$9 – Seniors/ Students

$8.00 – Horror/ Fantasy Series Films

$20.00 – Opening Night

Main Number to Call is Festival Box Office: 416-324-9121

Advance Box Offices:

ORDER TICKETS ONLINE FROM TJFF.COM.

In Person – Toronto Jewish Film Festival Box Office (basement level), 19 Madison Ave., Sunday – Friday 12p.m. – 6p.m. No wheelchair access. Please call 416-324-9121 for assistance by phone.